Supporters of Syria Take Significant Steps, but No Endgame in Sight

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 9 Issue: 67

By:

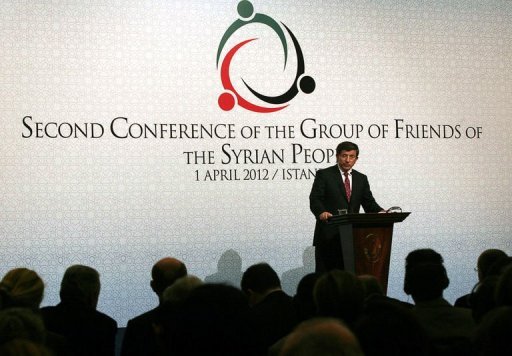

On April 1, Turkey hosted the second meeting of the Friends of Syria group, which produced mixed results as to the future of the Syrian uprisings. While the meeting lent some legitimacy to the opposition organized around the Syrian National Council (SNC) and warned President Bashar al-Assad not to miss a final chance for a political solution, it fell short of authorizing decisive actions that would coerce him to end the violent military campaign against the uprising and, more importantly, step down from power (Anadolu Ajansi, April 1).

Given its proximity and the close relationship it had forged with Damascus in the preceding years, Ankara has been actively involved in the resolution of the Syrian crisis since the beginning of the uprising. After the failure of its final efforts to reach out to Assad diplomatically in the summer of 2011, Turkey’s position changed drastically. Since then, Turkey, in coordination with the Arab League and its Western partners, has been at the forefront of the international initiatives to solve the crisis by removing Assad from power. It has extended shelter to both the Syrian refugees and the opposition groups and strived to push the UN Security Council to authorize stronger action to address the impending humanitarian catastrophe. The inability to involve the UN Security Council in the crisis due to the Russian and Chinese vetoes prompted Turkey to explore alternative avenues (EDM, February 7).

Although at one point the Turkish government came under growing international pressure to lead a military intervention into Syria, it resisted such calls and instead continued to explore other means to first alleviate the suffering of civilians and later to ensure Syrian regime change. In an effort to generate broader international momentum around these objectives, Turkey was instrumental in the formation of the Friends of Syria group, bringing together likeminded states, which held its first meeting in Tunis a month ago. However, as it facilitated this coalition acting in close concert with the Washington, Ankara also risked fundamental disagreements with the supporters of the Syrian regime, especially Tehran, which added one more element to the already complicated bilateral relations.

In the weeks preceding the meeting, Turkey also worked hard to ensure that it would produce substantial outcomes. Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan, attending the nuclear summit in South Korea, discussed this issue with US President Barack Obama and Russian President Dmitry Medvedev, hoping to change Moscow’s position by sending the message that Assad’s days are numbered and those who stand behind him will be doomed to lose (Hurriyet, March 28). On his way back home, Erdogan visited Iran and met with Iranian leaders, including the religious leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei (www.haberturk.com, March 29). Erdogan’s appeal to his Iranian counterparts was hardly successful, as they gave no indications of a change in their position. Turkey also maintained its coordination with the Arab League, but the internal divisions among the Arab countries increasingly became apparent. While the Gulf states largely supported the Syrian opposition, Iraq has cautioned against overbearing action against Damascus and expressed its discomfort with Turkey’s activism by not inviting it to the Arab League meeting only days before the Friends of Syria conference in Istanbul (Haberturk, March 29).

The game changer ahead of the Friends’ meeting was the six-point plan prepared by the UN/ Arab League joint special envoy Kofi Annan. After his diplomatic tour, Annan submitted his plan to the UN Security Council. The Annan plan foresees a cessation of violence, delivery of humanitarian assistance, withdrawal of heavy weaponry out of civilian areas, and political dialogue, but falls short of meeting the opposition’s demand for outlining a program for the transfer of power. Following a Security Council presidential statement giving full support to the plan on March 21, the Syrian regime also agreed to accept it on March 27 (www.aljazeera.com, March 28). Though Annan emphasized that the implementation will be the key, Assad’s move right before the Istanbul conference apparently sought to open some cracks in the coalition and thwart a harsh response.

This development put Turkey in a difficult position, as it still operated under the assumption that changing the regime would be needed to solve the crisis. Erdogan raised concerns about Assad’s sincerity, arguing that he had failed to keep his earlier reform promises (Vatan, March 28). More importantly, Turkey questioned the six-point plan because it lacked a clear time table and enforcement mechanism in case of noncompliance (Sabah, March 31).

Turkey also took a major step in advance of the Friends conference by convening the Syrian opposition groups in Istanbul, which sought to consolidate the opposition under one structure. By then, the disunity of the opposition groups had prevented a more decisive international support to the SNC. Although they achieved major progress in the way of eliminating differences of opinion, outlining a plan of action for national unity and consolidating their leadership structure, the withdrawal of the Syrian Kurds indicated the remaining divisions (www.ntvmsnbc.com, March 28).

The Istanbul conference produced mixed results. The participation of over 70 countries and several international organizations, despite the absence of Russia and China, was in itself a major success. In a lukewarm development, the participants recognized the SNC as a legitimate, though not the sole, representative of the Syrian people, and decided to treat it as an interlocutor in the conflict. Though the lack of a clear decision to arm the opposition or establish humanitarian corridors also fell short of the SNC’s expectations, the references to supporting the Syrian people’s legitimate right to defend themselves might open such a loophole. The participants still agreed to establish a fund, to be provided largely by the Gulf countries as well as some Western nations, to extend financial assistance to the Free Syrian Army and supply it with some communications equipment. Also important was a decision to establish a working group to monitor the arms embargo as well as to document violations of human rights, which might increase pressure on Assad and his backers. Though the meeting supported Annan’s plan, it also called on him to set a timeline for its implementation. Although Turkey and the Friends group assume that Assad’s end is inevitable, their progress in compelling Assad and his supporters to change their behavior has been far from impressive. It might be too early to tell the endgame in Syria.