Syria in China’s New Silk Road Strategy

Publication: China Brief Volume: 10 Issue: 8

By:

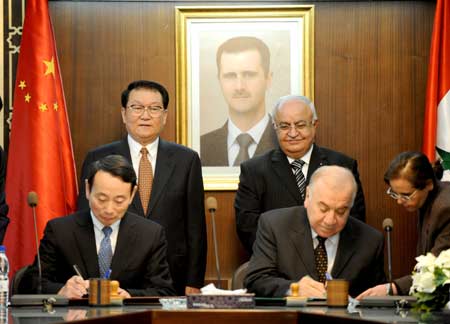

While the international community is fixated on Iran’s nuclear program, China has been steadily expanding its political, economic and strategic ties with Syria. Since Syrian President Bashar al-Assad visited China in 2004 on the heels of the 2003 U.S. intervention in Iraq, there have been increased economic cooperation and more recently, a flurry of high-level exchanges on political and strategic issues. On April 5, while at the 7th Syrian International Oil and Gas Exhibition “SYROIL 2010” to attract local, Arab and foreign investors, Syrian Minister of Petroleum and Mineral Resources Sufian al-Allaw told the state-run Xinhua News Agency that he expects more contracts and cooperation with Chinese oil companies (Xinhua News Agency, April 5). This is in tandem with growing political and economic cooperation in the electricity, transport and telecommunications sectors dominated by Chinese enterprises such as CNPC, ZTE, Huawei and Haier (China’s largest white goods manufacturer) (Xinhua News Agency, March 31, 2008; The Syrian Report, May 11, 2009).

The Middle East was an important bridge between Asia and Europe along the ancient Silk Road and since 1991, China has been rebuilding the Silk Road through the construction of a network of highways, pipelines, and rail lines from China to re-link the countries of Central Asia and Europe along this historic corridor (Georgian Daily, January 27). Beijing’s renewed interest in Damascus—the traditional terminus node of the ancient Silk Road—in spite of Syria’s current status as an international pariah, indicates that China sees Syria as an important trading hub and partner for Chinese interests in Africa, Europe and the Middle East. Indeed, China dubs Damascus "ning jiu li," or "cohesive force," and Damascus is serving as a cohesive force as China’s Silk Road strategy converges with Syria’s "Look East" policy toward China (The Syrian Report, May 11, 2009; Gulf News, January 12).

China’s Perception of Syria and the Middle East

Syria is part and parcel of China’s broader Middle East strategy, which Jin Liangxiang, research fellow at Shanghai Institute for International Studie, argued is going through a new activism and that “the age of Chinese passivity in the Middle East is over” [1]. According to a 2004 interview with Ambassador Wu Jianmin [2], considered to be one of China’s most outstanding diplomats one who witnessed and contributed to the development of Chinese diplomacy, Chinese foreign policy was transforming from "responsive diplomacy" (Fanying shi waijiao) to "proactive diplomacy" (Zhudong shi waijiao) (China Youth Daily, Feb 18, 2004) [3].

Indeed, since the 2003 U.S. intervention in Iraq, China has become more active in prosecuting a “counter-encirclement strategy” against perceived U.S. hegemony in the Middle East [4]. Then Chinese Foreign Minister Qian Qichen blasted U.S. foreign policy in a China Daily article that the United States has “put forward its ‘Big Middle East’ reform program … the U.S. case in Iraq has caused the Muslim world and Arab countries to believe that the super power already regards them as targets of its ambitious ‘democratic reform program’ (China Daily, November 1, 2004). Beijing fears that Washington’s Middle East strategy entails advancing the encirclement of China and creating a norm of regime change against undemocratic states, which implicitly challenges the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) legitimacy at home. To counter that, China has increased economic and diplomatic ties with countries in the region, worked to establish a China-GCC free trade zone (Gulf News, March 28), established Sino-Arab Cooperation Forum (China Daily, January 30, 2004), and overall increased its footprint in the region. Jin Liangxiang declared that “if U.S. strategic calculations in the Middle East do not take Chinese interests into account, then they will not reflect reality” [5].

Syria as China’s foothold into the Mediterranean Union

Other than its geographic location as a terminus node on the ancient Silk Road, and hub for trade between the three continents of Africa, Asia and Europe, there are many reasons for China’s interest in Syria. First, it can serve as China’s gateway for European market access in the face of increasing protectionist pressures from larger countries such as France, Germany and Great Britain within the European Union (EU). As such, China has launched a strategy of investing in small countries and territories poised to join the EU in the Balkans or the Levant that forms the Mediterranean Union, which was initiated by the 1995 Barcelona Process to create a free trade zone between EU and countries in North Africa and the Middle East along the Mediterranean Coast. For example, Chinese Vice-President Xi Jinping in October 2009 called on larger Balkan countries that were already EU members, such as Hungary, Bulgara and Romania, to serve as links to smaller Balkan countries that have yet to join the EU (See "Xi’s European Tour: China’s Central-Eastern European Strategy Reaches for New Heights," China Brief, October 7, 2009). Syria is close to the EU and Mediterranean, but has yet to sign an agreement with the Mediterranean Union [6].

China’s strategy in Syria as a beachhead into the EU market is similar to its strategy toward the Balkans. In recent years small countries in the Balkans such as Serbia, Bosnia, Slovenia, Macedonia, Moldova and so on have seen an increase in Chinese investment in infrastructure projects and generous loans (World Security Network, March 8). Some European analysts such as Dusan Reljic from the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, SWP) have described the Chinese arrival in the Balkans as an effort to get into Europe through its backdoor. Reljic says that a direct route to greater EU presence is more costly for China than investing in territories poised to join the EU within 10 to 15 years. "It’s cheaper to buy assets there than within the European Union," he said (Deutsche Welle, March 4). Similarly, with Syria poised to sign the Association Agreement with the Mediterranean Union, China’s investment in Syria would eventually gain a beachhead and foothold into the EU market via the Mediterranean Union (Global Arab Network, October 16, 2009) [7].

Syria as a trading hub for China’s interests in Africa, Middle East and Europe

Second, Syria’s proximity to a large trading bloc of the EU and some of the fastest growing economies in the world in Africa, the Middle East and Asia would enhance its role as a trading hub via the "neighborhood effect," whereby factories will be placed in locations closer to both suppliers and consumers of products. Thus, Syria as a node on the Silk Road can be reborn as a regional outsourcing distribution center poised to take advantage of positive externalities of this neighborhood effect. Syria is already on track to slowly reforming its economy; it is self-sufficient in energy with a power grid linked to Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey; and it is taking steps to privatize the banking system and planning to set up a Damascus stock exchange. China thus is establishing first mover advantages to secure competitive pricing in a country that is methodically taking steps to reform its economy (Forward Magazine, January 26, 2009). Indeed, China is already using Damascus as a springboard to the region, with "China City" in Adra Free Zone industrial park located 25 km north east of Damascus on the Damascus-Baghdad highway, established by entrepreneurs from the wealthy Chinese coastal province of Zhejiang, to sell Chinese goods and as a major trans-shipment hub onto Iraq, Lebanon and the wider region (Forbes, May 21, 2009) [8]. China City is especially popular among visiting officials from Iraq, where China is currently the biggest oil and gas investor (Middle East Information, March 17; Aswat al-Iraq, April 1; Business Insider, February 2).

Syria as a key node for China’s Iron Silk Road

Third, China is interested in building a Eurasian railway network connecting Central Asia through the Middle East and onto Europe (Railway Insider, March 11; The Transport Politic, March 9). Under the auspices of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), China is already negotiating to change Kyrgyzstan’s soviet tracks of 1,520 mm to the international standard of 1,435 mm in order to connect with Turkish and Iranian railway systems (Georgian Daily, January 27). The network would eventually carry passengers from London to Beijing and then to Singapore and run to India and Pakistan, according to Wang Mengshu, a member of the Chinese Academy of Engineering and a senior consultant on China’s domestic high-speed rail project (Daily Telegraph, March 8). There will be three main routes, with one connecting to Southeast Asia as far as Singapore, the second one from Urumqi in Xinjiang Province through Central Asian countries onto Germany, and the third from Heilongjiang in northern China with Eastern and South Eastern European countries via Russia (Xinhua News Agency, March 12). Wang said China is already negotiating with 17 countries over the rail lines, and is in the middle of a domestic expansion project to build nearly 19,000 miles of new railways in the next five years to connect major cities with high-speed lines [9].

Syria in December 2009 began discussing railway cooperation with Italian State Railway (Italferr) in Damascus, in order to upgrade the Damascus-Aleppo line as part of a network connecting Turkey toward Europe, and Jordan toward Saudi Arabia and the Gulf, said Syrian Minister of Transport Yarob Bader (European Business Centre (SEBC) Syria, December 6, 2009). Syria also wants to build railways from the coastal city of Tartous to Umm Qasr port in southern Iraq, and use its Mediterranean port to build trade routes between Iraq and Europe (The Wall Street Journal, June 1, 2009). This bodes well for China’s energy holdings in Iraq—where it is building a big presence—as China and Syria already held discussions on building a natural gas pipeline from Iraq’s western Akhas fields to Syria, which could be an attractive transit point for gas-starved Arab and European markets (The Wall Street Journal, April 1).

Syria’s ‘Look East’ Policy toward China

Similarly, China is of great strategic value to Syria during a time when the West is trying to isolate it. When the doors to Europe and the United States were closed to Damascus in 2005 following allegations of Syrian involvement in Lebanese Prime Minister Hariri’s assassination, foreign policy chiefs decided to look East to replace the vacuum of the West. Buthaina Shaaban, the current presidential adviser on media affairs, penned an article then outlining this approach: "Perhaps the time has come to bring the Arabs, from a state of complete submission to the hostile West, towards [sic] the East and countries that share with us values, interests and orientation." She added, "What did we get from the West, to which the Arabs affiliated themselves for the entire past century, except for occupation, hatred and war?" (Gulf News, January 12).

Conclusion

Syria is proving to be an important Ning Jiu Li node on China’s Silk Road. With China’s new activism and its aspirations to eventually join the Middle East Quartet in shaping the Arab-Israeli peace process (Xinhua News Agency, December 16, 2006), Syria is emerging as a key partner in China’s broader Silk Road Strategy for “peaceful and harmonious development” in the Mediterranean region. Indeed, Henry Kissinger proclaimed that in the Middle East, there is “no war without Egypt, no peace without Syria.” As China becomes more engaged in the Middle East region and Syria is "looking east" to what it perceives may be a new Pax Sinica, the international community needs to pay heed to this burgeoning partnership and begin to factor in China as an important player in the greater Middle East and Mediterranean geopolitical landscape.

Notes

1. "Energy First: China and the Middle East” by Jin Liangxiang, Shanghai Institute for International Studies, Middle East Quarterly, Spring 2005, pp. 3-10.

2. Ambassador Wu Jianmin is currently professor at the China Foreign Affairs University (CFAU) and Chairman of the Shanghai Centre of International Studies (The Globalist, “Biography of Wu Jianmin, November 16, 2009). He is also Vice-Chairman of the prestigious Institute of Strategy and Management, and has a distinguished diplomatic career, having interpreted many times for Chairman Mao Zedong, Premier Zhou Enlai and other State leaders from 1959-1971 as a young diplomat. Chinese Radio International in 2009 dubbed him “one of China’s most outstanding diplomats…as one who witnessed and contributed to the development of China’s diplomacy.” (Chen Zhe, “Senior Diplomat Wu Jianmin,” (CRI English, February 18, 2009).

3. "Energy First: China and the Middle East” by Jin Liangxiang, Shanghai Institute for International Studies, Middle East Quarterly, Spring 2005, pp. 3-10.

4. Dan Blumenthal, “Providing Arms: China and the Middle East,” Middle East Quarterly, Spring 2005, pp.11-19.

5. Jin Liangxiang, “Energy First: China and the Middle East”.

6. Anja Zorob, "Partnership with the European Union: Hopes, risks and challenges for the Syrian economy” in Fred H. Lawson ed., Demystifying Syria (London: London Middle East Institute, SOAS, 2009), p.153.

7. "Anja Zorob, "Partnership with the European Union: Hopes, risks and challenges for the Syrian economy” in Fred H. Lawson ed., Demystifying Syria (London: London Middle East Institute, SOAS, 2009).

8. The New Silk Road: How a rising Arab world is turning away from the West and rediscovering China (Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), p.81.

9. Ibid.