The China Factor in India-Japan Relations

Publication: China Brief Volume: 14 Issue: 2

By:

New Delhi has invited Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe to be the chief guest at its annual Republic Day parade, which celebrates both Indian democracy, but also showcases its military. One country in particular that will be keenly watching the visit, which will commence on January 26, is China. The invitation is extended after careful consideration, in recognition of the country’s strategic significance to India. Although the visit must have been planned long in advance, its timing is fraught with speculation in the context of the spat over China’s unilateral declaration of an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) on November 23 last year, with the visit of Abe to the war memorial Yasukuni Shrine exacerbating the strained relationship between China and Japan. Abe’s visit is taking place close on the heels of a visit by Japanese Defense Minister Itsunori Onodera earlier this month, and the visit of the Emperor Akihito in November and December last year, not to mention the recent adoption of Japan’s National Security Strategy and the National Defense Program Guidelines.

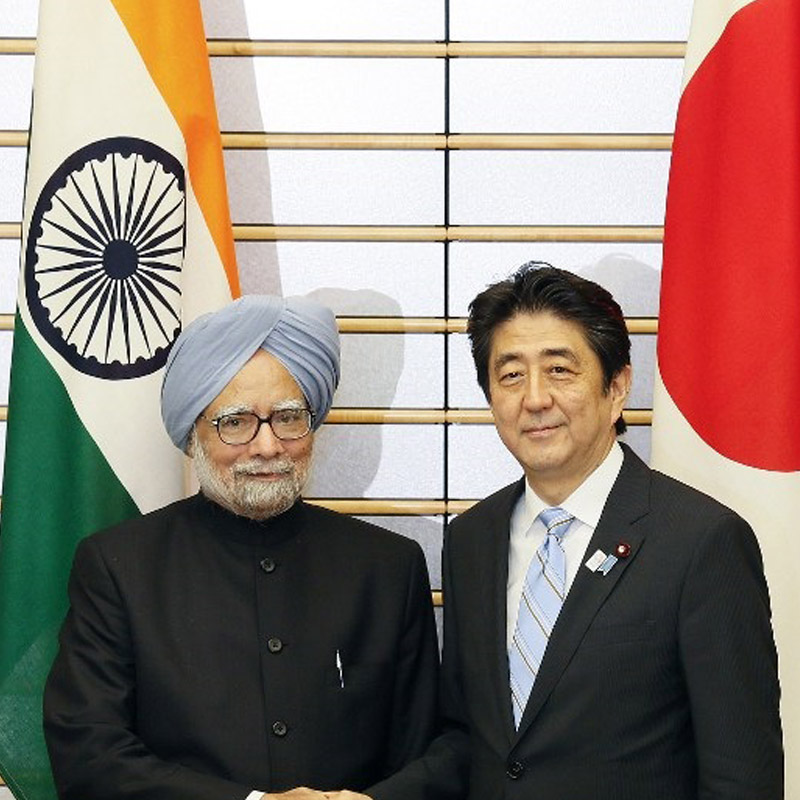

Although the India-Japan relationship has its own driving forces in terms of robust economic ties and shared values, China is the elephant in the room in the strategic parleys between the two countries. The current Japanese leadership has been very proactive in attempting to forge a strategic partnership and to deepen the defense and security relationship with India, seeking to hedge China. Prime Minister Abe has been most active in this regard. India has, however, been very circumspect in response to Japanese overtures, out of concern for Chinese sensitivity. India and Japan signed the joint statement towards Japa-India Strategic and Global Partnership during the visit of Prime Minister Manmohan Singh to Japan in 2006, when Shinzo Abe was the Prime Minister (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan [MOFA-J], December 15, 2006, text at < https://www.mofa.go.jp/region/asia-paci/india/pdfs/joint0612.pdf >). Later, the two countries signed the Joint Statement Vision for Japan-Indian Strategic and Global Partnership in the Next Decade, during the visit of Prime Minister Manmohan Singh to Japan in October, 2010 (MOFA-J October 25, 2010, text at < https://www.mofa.go.jp/region/asia-paci/india/pm1010/joint_st.html >). It is no coincidence that India and Japan elevated their relationship to a strategic level at the time of rising Chinese assertiveness in the South China Sea and East China Sea.

As John Garver and Fei-Ling Wang wrote in “China’s Anti-Encirclement Struggle,” a prime “objective of Chinese diplomacy has long been to prevent China’s neighbors from moving into alignment with the United States, and with one another to counter China’s rise” (Asian Security, Volume 6, Issue 3 (2010)). As such, China’s strategy has aimed to dissuade India from partnering with Japan to oppose China. Thus, its rhetoric on India-Japan strategic partnership has been very conciliatory, while at the same time being critical of Japan. For example, when Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh visited Japan in October last year, after the incursion of the Chinese into the Indian side of the Line of Actual Control in the in Depsang in Ladakh region on April 15, and described Japan as India’s “indispensable and natural ally,” an article in the Global Times said, “…Unlike Sino-Japanese disputes over the Diaoyu islands in which Japan is determined to escalate the situation, Sino-Indian border issues generally been peaceful and stable since the first round of border talks in 2003, which did not solve the whole issue but showed a mutual willingness to talk” (Global Times, October 22, 2013). Addressing the skewed nature of Sino-Indian bilateral trade in favor of China, which has been an issue of concern to India, the article further said, “Some might quote stagnating bilateral economic ties for gloomy future relations, but economic ties are never the determining factor on bilateral political relations. Japan and China have strong economic ties, but these cannot prevent their political distrust and worsening relations.” The Chinese message to Japan is very clear: Sino-Indian relations will remain good in spite of the border dispute and ballooning trade deficit, as long as India does not side with Japan in its dispute with China.

It may also be noted in this context that in order to preempt any kind of Indian support to Japan, PRC spokespeople said within few days of its ADIZ declaration that there was “no question” of its establishing a similar zone near its border with India. Foreign Ministry spokesperson Qin Gang said, “I want to clarify on the concept of an ADIZ, that it is an area of airspace established by a coastal State beyond its territorial airspace.” (The Hindu, November 29, 2013). India maintained a studied silence on China’s ADIZ during the visit of Japanese Emperor Akihito. Of course, the visit of the Japanese emperor by its very nature was symbolic. A report in the Hindustan Times quoted senior officials on conditions of anonymity saying that New Delhi didn’t have to “join the issue” on the ADIZ or “make its position known” (Hindustan Times, December 3, 2013). The report further quoted its sources saying, “We have been managing our differences with China, and we both focus on many areas of cooperation that exists between us. The issue [of the ADIZ] is not something we think we are compelled to respond to.” The Japanese Defense Minister, during his recent visit to India ahead of Abe’s visit, explained the security implications of the Chinese move to create the ADIZ over the disputed island. The joint statement issued after the visit is, however, conspicuously silent on the issue. It simply said that the two ministers “frankly exchanged ideas regarding regional and global security challenges, as well as bilateral defense cooperation and exchanges between India and Japan” (“India and Japan hold Defense Talks,” Indian Press Information Bureau, January 6).

India has shown no sign of endorsing Japan’s hardening posture towards China, as can be gauged from a statement made by India’s External Affairs Minister Salman Khurshid about Abe’s visit to Yashukuni Shrine. While was speaking with Natsuo Yamaguchi, the leader of the New Komeito Party in Japan’s ruling coalition, he said that Japan should learn from history and move on (Xinhua, January 8).

Taking a cue from Khurshid’s utterance, the Chinese Ambassador to India, Wei Wei, used an article in the Indian Express to allude to the seminal role played by an Indian medical mission under the legendary doctor Dwarkanath Kotnis, whom Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru had deputed to China during the Sino-Japanese war in 1936 (Indian Express, January 10) to treat the wounded soldiers. The article further said “With assistance from the US and the United Kingdom, Indian and Chinese soldiers together fought against Japanese aggression in India,” urging India not to forget this shared history.

Given the degree of security distrust between Japan and China, and being conscious of Chinese wariness, New Delhi has been sensitive to Chinese anxieties, and has sought to avoid being seen as teaming up with Japan to balance China. But if the signals of strategic depth and security and defense cooperation between India and Japan are decoded, China-oriented intent comes through loud and clear in terms such as “maritime cooperation,” “freedom of navigation” and “sea-lines of communication.” The Joint Declaration on Security Cooperation between India and Japan signed in 2008 during the visit of Prime Minister Manmohan Singh to Japan is the only such document that India has ever signed with any other country. It recognizes “that a strong and prosperous India is in the interests of Japan and that a strong and prosperous Japan is in the interests of India” (Indian Press Information Bureau, October 22, 2008). It then adds that “India and Japan share common interests in the safety of sea lines of communications.” Regarding the mechanisms of maritime cooperation, it says, “The two Coast Guards will continue to promote cooperation to ensure maritime safety, maritime security and protect the marine environment through joint exercises and meetings between the two Coast Guards.” It is true that the bulk of the trade of Japan and that of India are sea borne. Also energy security entails safety of sea lines of communications. But maritime cooperation is omnibus, and it signals more than what meets the eyes. Although India has not directly articulated that China poses threat to the freedom of navigation in the South-China Sea, its endorsement for freedom of navigation and Sea Lines Of Communications (SLOCs) has riled China (See China Brief, October 10, 2013).

The expectations from the Japanese side are high, but India does not plan to ruffle feathers with its mighty northern neighbor, with which it shares a reasonably good working relationship. What brings India and Japan together is not only the complementary economic interests, but also the convergence of security and strategic concerns in the context of an assertive China. Japan’s adversarial relationship with China, and India’s security dilemma toward China, provides glue to defense and security cooperation between India and Japan. India, however, is not inclined to forge any security policy that targets a specific country. As Prime Minister Dr. Manmohan Singh during his recent visit to China in October, while addressing the Central Party School in Beijing said, “Old theories of alliance and containment are no longer relevant. India and China cannot be contained …Nor should we try to contain others… Our strategic partnerships with other countries are defined by our own economic interests, needs and aspirations. They are not directed against China or anyone else. We expect a similar approach from China” (The Hindu, October 24, 2013). India expects that defense cooperation with Japan will improve its military capabilities. Besides, India’s 1 trillion dollar infrastructural projects including the possibilities of introduction of high speed rail also offers very good opportunity to Japan for a robust economic engagement.

India’s trust deficit with China puts Japan in an advantageous position in this respect. As far as defense cooperation between the two countries is concerned, as of now, it is by-and-large limited to joint naval exercises between the Coast Guards of the two countries. India’s defense modernization and procurements can offer opportunities for Japan to forge a closer partnership, depending on the extent to which Japan liberalizes its defense exports and transfer of technology and joint-production. As Japan attempts to form common cause with India in the region, arms sales will be a crucial area to watch.