The Four Main Groups Challenging Xi Jinping

The Four Main Groups Challenging Xi Jinping

Executive Summary:

- Xi Jinping faces challenges to his authority from four main groups: retired party elders such as Li Ruihuan and Wen Jiabao; princelings, especially those based overseas; military leaders, such as Zhang Youxia; and parts of the middle and entrepreneurial classes who are voicing their discontent.

- Xi is unlikely to be overthrown or face a coup, but his ability to force through his agenda may be reduced.

- Indicators that Xi is embattled include his absence from chairing two recent high-level meetings, references to “collective leadership” the PLA Daily newspaper, and an adjustment to PRC diplomacy to a more conciliatory approach, especially toward the United States.

- This apparent reduction in power could be a result of the country’s bleak economic situation, which Xi’s policies from last year have not resolved.

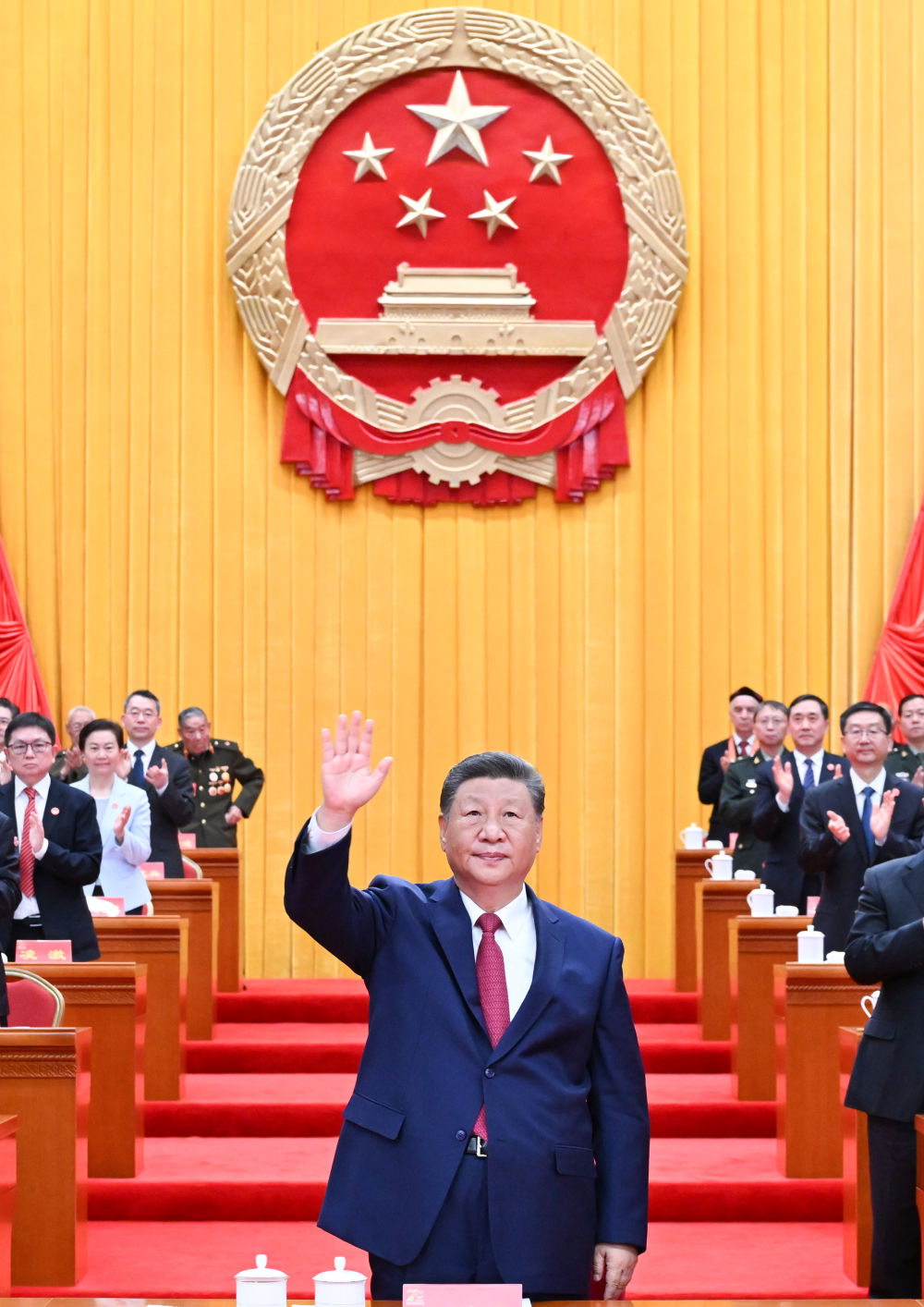

Xi Jinping is in political trouble. The supreme leader of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) faces challenges from multiple groups, including from retired politburo standing committee members, fellow princelings, some of the military top brass, and even from some in the country’s middle class. As a result, his ability to shape policy in the financial, foreign affairs, and other arenas has been truncated. It might be far-fetched to speculate that Xi, the so-called “eternal core of the Party (永远党的核心),” might be driven out of office this year, but it is crucial to understand who his enemies are and how they challenge the commander-in-chief.

The PLA Daily, the official newspaper of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), recently have championed the virtues of “collective leadership (集体领导).” This could be interpreted as a slap in the face of Xi’s insistence since he came to power in 2012 on the dictum that all decisions should “rely on a single voice of authority (定于一尊)” (PLA Daily, December 9, 2024; Radio Free Asia, December 18, 2024).

Xi’s clout over economic decision-making appears to have been reduced. The Central Financial and Economic Affairs Commission and the Central Comprehensively Deepening Reforms Commission, which are the two major high-level party platforms for promulgating economic and financial policies that Xi leads, have ceased to meet regularly (Fitch Ratings, December 16, 2024; State Council, January 5; (Radio Free Asia, January 10). This could be due to the underwhelming results of the massive program of monetary and fiscal quantitative easing—known to Chinese officials as “using ample water to undertake massive irrigation (大水漫灌)”—that has been executed since September (China Brief, October 11, 2024).

The PRC also seems to be enacting a temporary adjustment to its foreign policy. Faced with lackadaisical prospects for exports as well as the coordinated withdrawal from the PRC of multinationals based in the United States and its allies, Xi has been forced to jettison the typically abrasive brand of “wolf warrior” diplomacy, instead emphasizing eagerness to improve relations with Washington and the West (VOA Chinese, November 17, 2024; CCTV, January 4; CGTN, January 11). This shift is underlined by rumors that Xi intends to send a senior official to the inauguration of U.S. President Donald Trump on January 20 (World Journal, January 11).

Xi Face Four Challengers

Retired Politburo Standing Committee Members

Xi has imposed heavy restrictions on the activities and movements of party elders since his first day in office. These former party heavyweights, often retired members of the Politburo Standing Committee, include supporters of the market-oriented policies of Deng Xiaoping, key economic officials under former premiers Zhu Rongji and Wen Jiabao, and former top government advisors such as Li Ruihuan (李瑞环). Security staff reporting to Xi Jinping’s office have changed the personnel who work for these men, such as their secretaries and drivers, and disallowed them from holding meetings or travelling to other parts of country without the approval of the supreme leader (Radio Free Asia, January 10).

Behind closed doors, many of these elders have expressed disapproval of Xi’s handling of economic issues and relations with the United States since the third plenary session of the 20th CCP Central Committee last July (China Brief, July 23; July 26). At a banquet on the eve of the country’s National Day on October 1, 2024, Wen Jiabao and Li Ruihuan sat on either side of Xi (Lianhe Zaobao, September 30, 2024). This was regarded as a subtle signal by Xi that he was receptive to advice or warnings from former senior leaders, even if they lack the authority to remove him. Their barely concealed critique of Xi’s policy-making prowess suggests the supreme leader may be increasingly at odds with parts of the CCP’s top echelon (Vision Times, August 17, 2024; Nikkei, October 24, 2024).

Princelings

The possession of “red genes (红色基因)” has traditionally been a prerequisite for accession to top leadership positions (Qiushi, March 13, 2024). Xi, a princeling himself, has spent years attempting to marginalize those he regards as potential competitors. Such maneuvering predates his promotion to CCP general secretary, with prominent targets including as Bo Xilai (薄熙来), whose father Bo Yibo (薄一波) was one of the so-called “Eight Immortals” (Party elders who held substantial sway at the end of the 20th Century), and General Liu Yuan (刘源), son of Liu Shaoqi (刘少奇), the former state president who was at one time considered a potential successor to Mao.

Many princelings have become Xi’s fiercest critics, especially those based overseas. Many of these individuals grew rich through leveraging their sterling political and business connections in the PRC, before parking billions of dollars of accumulated wealth in North America and Europe and subsequently exiting the PRC with their families. To ensure that they are not harassed by their chosen countries of residence, a number of these former cadres have opted to cooperate with local intelligence agencies. The information they have provided likely includes kompromat against Xi Jinping, though it is unclear what this might include, or how it could be used against him (The Economist, April 4, 2024; Radio Free Asia, January 10).

Military Top Brass

Xi’s loss of substantial control over personnel arrangements among the PLA top brass became obvious when several high-level meetings of senior officers were hosted by General Zhang Youxia (张又侠), the first-ranked vice-chairman of the Central Military Commission, the top-level body that controls the military. Xi was absent from those meetings (MND, September 13, 2024; MND, October 22, 2024). A veteran of the military forces’ equipment procurement and missile forces, Zhang was the boss of the two defense ministers—Generals Li Shangfu (李尚福) and Wei Fenghe (魏凤和)—that Xi fired in 2023 and 2024, respectively. The recent investigation of the director of the CMC Political Work Department, Admiral Miao Hua (苗华), as well as that of around a dozen rising stars in the PLA Navy, may be a result of Xi’s opponents in the PLA trying to get rid of his loyalists, including a number of officers who had worked with Xi during his time in Fujian Province in 1985–2002 (RFI, November 30, 2024; December 23, 2024).

Zhang is unlikely to seek to overthrow Xi. This is in part because of the ingrained tradition of the Party’s “absolute leadership (绝对领导)” over the military, and in part because Zhang is due to retire in 2027, at which point he will be aged 77. The military impact of personnel issues at the top of the military remains an open question. Some suggest that it could detract from the perceived ability of the CCP leadership to take over Taiwan and to assert military domination over the South China Sea and the Sea of Japan (Taiwan Institute of Chinese Communist Studies, December 31, 2024; VOAChinese, August 30, 2024). The PLA has nevertheless made significant gains in recent years in spite of corruption within its ranks (U.S. DOD, December 2024).

Social Unrest

Social discontent appears to be on the rise in a number of sectors of society where there has been a rise in explicitly anti-Party—and even anti-Xi—activities. These appear to consist largely of victims of Xi’s policies, including those that prioritize state-owned enterprises at the expense of private capital, those that have led to mass unemployment for graduates from high-schools and colleges, and those that have created the conditions for the current economic downturn. Members of the middle class who still can get foreign exchange on the black market are voting with their feet by moving overseas. This is in addition to the tens of thousands of mainly low-income Chinese who are estimated to have attempted to flee to the United States via Central America in the past year. Such a journey is treacherous, involving paying organized crime groups and traffickers for passage to the U.S. border (Wall Street Journal, April 16, 2023; VOA Chinese, April 2, 2024; BBC Chinese, April 1, 2024).

An emblematic example is the recent explosion of anti-government feelings in the city of Pucheng, Shaanxi Province. An apparent coverup by authorities following a case of a student jumping to his death from the dormitory of a local vocational college led to violent protests by Chinese citizens expressing growing intolerance of special privilege and extreme censorship. The student, surnamed Dang, had suffered repeated bullying from classmates. As these classmates had Party connections, the local police refused to either open investigations into or provide detailed information about the incident (CNN, January 11; BBC, January 11). This latest story follows a series of violent attacks by citizens aggrieved by the party and government late last year that killed tens of people across the country. Retired and decommissioned soldiers also regularly confront police or People’s Armed Police officers with sophisticated weapons and illegally procured fire arms (NPR, November 12, 2024; China Brief, December 3, 2024; IHR360.com, January 8). [1]

Conclusion

The gradual though relentless dwindling of Xi’s authority could adversely impact on Beijing’s plans to reflate the economy or to repair relations with the West. On the economic side, the monetary and fiscal stimulus announced since September is far from sufficient to assuage local government debt. A January 2025 decision to allow relatively rich localities to issue bonds without central authorization could further exacerbate their indebtedness. Even successful firms in booming sectors are facing problems. For instance, electric vehicle manufacturer BYD has a debt to asset ratio of more than 70 percent, according to Radio Free Asia; and its competitor SAIC has concerns about its profits squeezed by tariffs imposed by the European Union (Digitimes Asia, September 24, 2024; Sina Finance, November 13, 2024; Radio Free Asia, November 27, 2024; Gov.cn, January 10).

On the political side, despite Xi’s apparent willingness to engage with the incoming Trump administration, a lack of restraint in the PRC’s demonstration of hard power in the South China Sea and that Taiwan Strait suggests he is unlikely to win concessions on export controls in critical technologies. Xi seems uninterested in changing course. The continued lack of reports on his succession planning reinforces the sense that he intends to remain in power until 2032. Barring major policy shifts, improvements are to be found at the margins through the pursuit of “self-perfection [techniques] (自我完善)” and “self-revolution (自我革命);” in other words, by leaning into asceticism and putting the onus on individuals to be more productive at the expense of changing structural incentives to achieve tangible economic growth (China Brief, January 19, 2024; CCTV, January 8; People’s Daily, January 16).

Notes

[1] On contentious veterans, see: O’Brien, Kevin J., and Neil J. Diamant. “Contentious Veterans: China’s Retired Officers Speak Out.” Armed Forces & Society 41, no. 3 (2015): 563–81. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48669883.