The Jihadist Threat in Italy

The Jihadist Threat in Italy

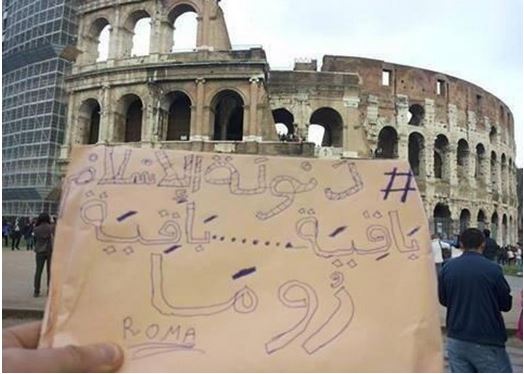

In recent months, a number of incidents have brought attention to the possible threat to Italy from cells or individuals linked to the Islamic State. For instance, since mid-April, some pictures of self-proclaimed Islamic State supporters have been circulating on the web, in which Italy was threatened in written messages held in front of symbolic places such as the Colosseum in Rome and the Duomo in Milan. Also in recent months, a Moroccan citizen was arrested near Milan over his involvement in the attack against the Bardo Museum in Tunis last March. This article seeks to assess to what extent these events constitute a serious security threat against Italy.

Between ‘Old’ and ‘New’ Jihadism

Since the 1990s, Italy has been at the center of Islamic terrorist networks, although it was not a direct target of jihadism. The main cause was its geographical proximity to North Africa to the south and the Balkans to the east, at a time when this area was affected by the most serious European conflict since the Second World War. In those years, Bosnia witnessed the rise of jihadist groups, and since then, there has been evidence that some individuals from the western Balkans have formed networks in Italy. On the other hand, in 2002, the Egyptian militant Abu al-Sirri (a.k.a. Abu Ammar) declared that Italy was a privileged transit point for jihadists going to Bosnia, and that it represented for Islamists what Pakistan represented for Afghanistan (La Repubblica, July 13, 2002). In this sense, the jihadist networks in Italy seemed averse to causing instability, which would have resulted in repressive measures against them by the government. This attitude changed in the wake of the 9/11 attacks and Italian participation in the international interventions in Afghanistan in 2001 and in Iraq in 2003. Since then, Rome has also been a potential target of Islamist terrorism. Nevertheless, there have been no attacks to date like those that took place in London and Madrid in 2005 and 2004, respectively.

However, this situation changed again after the so-called “Arab Spring” and the rise of the Islamic State in the Middle East, particularly after the establishment of the self-declared caliphate in 2014. At first, the focus was on the so-called foreign fighters who have gone to fight in Syria and Iraq, although this phenomenon is much less widespread in Italy than in other European countries. [1] Later, especially after the Charlie Hebdo attack in Paris in early 2015, Italian authorities have focused on the possibility that Italy could become a direct target. In January 2015, Italian Interior Minister Angelino Alfano announced that nine suspected militants had been expelled (Corriere della Sera, January 18). At the same time, however, Italian authorities have more than once declared that there is no evidence of an imminent attack in Italy (La Repubblica, January 9). Since April, a series of pictures have been circulating on the web, in which a self-proclaimed jihadist called Omar Moktar, was threatening Italy in front of some symbolic places (La Stampa, April 28; Terrorism Monitor, May 1). According to investigators and many analysts, it would not constitute a credible, or at least significant, new threat. Furthermore, it also appeared contradictory and amateur, with the picture of the Colosseum having been widely circulated since last June, with a picture of someone claiming to be the Italian self-styled jihadist actually depicting a Belgian jihadist who had died in Syria, and there are also Arabic grammatical mistakes. [2] More concretely, on May 20, the Italian authorities arrested Abelmajid Touil, a Moroccan citizen, for his alleged role in the March Bardo Museum attack in Tunis. The role that Touil actually played is unclear, and while Tunisian authorities initially said Touil was in Tunis the day of the attack, the Italian judiciary reportedly found evidences that he was in Italy (Tunisie Numerique, May 20; La Stampa, May 20). In light of such developments, Italian Undersecretary for Security Marco Minniti wrote in a recent report that the risk of attacks in Italy, although not concrete nor likely, remains “possible.” [3]

Italy as a Possible Target

Several sources of possible threats to Italy exist, due to political, cultural and geographical elements. Some risk factors are temporary, while others involve some longer-term structural aspects. These include:

- The generic identification of Italy with the West, which is considered by the new generation of jihadists as a land of infidels and, therefore, a legitimate target.

- Italy’s participation in the anti-Islamic State coalition.

- The presence on Italian territory of the Vatican, the global symbol of Christianity.

- The Pope’s recent announcement that a special Jubilee Year will start in December in Rome.

- The hosting of the Universal Exposition (Expo) in Milan for the next six months. The event will see the participation of the most important heads of state in the world and will certainly renew attention on Italy.

From the geographical point of view, Italy borders directly with some of the major theaters of instability where jihadism is being incubated:

- Libya: Currently Libya is the biggest concern for the Italian foreign and defense ministries due to the country’s ongoing civil war, which has made Libya a regional hub for North African jihadist groups. On several occasions, Libyan Islamic State-affiliated groups have explicitly threatened Italy (Il Sole 24 Ore, February 15). [4]

- Tunisia: Despite being the only country still going through a process of democratization after the so-called “Arab Spring,” Tunisia provides more foreign fighters than any other country in the world, and there is an on-going widespread radicalization among the younger generations. In addition, Tunisia is the closest North African country to Italy, and Italy, after France, is the country with the largest Tunisian migrant community. About a third of the 32 suspects expelled by Italy for security reasons linked to jihadism are Tunisians. On April 11, two Tunisian brothers living in Verona in northern Italy were expelled (La Repubblica, April 11).

- Egypt: Egypt provides generally fewer foreign fighters than countries like Tunisia. This is primarily because Egyptian jihadists are engaged directly on their territory, especially in Sinai. However, Egypt is part of the southern Mediterranean, and there is a regular flow of people from Egypt to Italy.

- Balkans: In past years, strong networks have developed between radical groups in Balkan countries, such as Bosnia, Kosovo, Albania and Macedonia, and Italy. In September 2014, Bosnian authorities arrested the Salafist preacher Bilal Bosnic, who, in summer 2014, recruited jihadists in northern Italy to fight in Syria and Iraq in the ranks of the Islamic State (Panorama, September 3, 2014; Il Fatto Quotidiano, September 4, 2014). Some of the foreign fighters that left Italy also originated in the Balkans, and the frequent contacts between Balkan communities and Italy accordingly attract high levels of attention from the Italian authorities.

Another source of Italian governmental concern is linked to illegal immigration. On May 12, the Minister of Information of Libya’s internationally-recognized government in Tobruk said that Islamic State fighters would infiltrate Italy in the next waves of migrants from western Libya (which is under the control of the rival Libyan government of Tripoli) (Corriere della Sera, May 12). To date, however, the Italian authorities have found no evidence of jihadists attempting to hide in refugees boats. In addition, the Tobruk government claims could hide a political purpose, namely to discredit the self-proclaimed Tripoli government in the eyes of Italy. It is worth noting that debate over this threat began in Italy after the arrest of Abelmajid Touil. The first reports said that Touil had arrived in Italy by boat together with other migrants last February (Corriere della Sera, May 20). However, Italian intelligence has underlined that there is not a single case of suspected extremists arriving by boat, out of almost 1,000 people investigated for suspected links with religious extremism (La Repubblica, May 20).

Conclusion

On April 15, the Italian government finally approved the anti-terrorism decree discussed on February 10 by the Council of Ministers (ANSA, April 15). Among the measures are new penalties for those who organize travel to fight in jihad abroad and for those who make jihadist propaganda, and there are also new crimes relating to self-radicalization and self-training. Moreover, the decree proposes the establishment of a black list of websites linked to jihadism. These measures are clearly aimed at tackling the phenomenon of so-called lone wolf attackers or individual jihadists. Currently, the main threat to Italy seems to come precisely from such quarters, with the secondary threat likely coming from the links between cells in Italy (especially in the north of the country) and jihadist groups abroad.

Stefano Maria Torelli, Ph.D., is a Research Fellow at the Italian Institute for International Political Studies (ISPI).

Notes

1. Out of the 5,000 foreign fighters that are supposed to have left Europe to fight in Syria and Iraq, only 57 have come from Italy. Only five of these hold an Italian passport. See also Lorenzo Vidino (ed.), L’Italia e il terrorismo in casa. Che fare?, ISPI, Milano, 2015. France would provide around 500 foreign fighters, United Kingdom and Belgium 400, Germany 240, Netherlands 140 and Denmark 100.

2. Here is the picture that was posted last April by the Italian Newspaper La Stampa: https://www.lastampa.it/2015/04/27/italia/cronache/isis-foto-con-messaggi-allitalia-siamo-tra-voi-ENmYjViw0ifM7oqJzoCwlN/pagina.html. Here is the same picture published by the Daily Mail on June 2014: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2663447/AllEyesOnIsis-Savvy-Jihadis-set-storm-Twitter-ISIS-propaganda-Q-A-10-30am-morning-Obama-prepares-air-strike-Iraq.html.

3. See Stefano M. Torelli, Arturo Varvelli (eds.), L’Italia e la minaccia jihadista. Quale politica estera?, ISPI, Milano, 2015.

4. In February, Italy was forced to evacuate its diplomatic mission from Libya, the last among the major Western countries to be still operating, due to the continuous threats. In the February video, in which Islamic State-affiliated militants showed the beheading of 21 Egyptian Coptic Christians on a Libyan beach, they said “We were in Syria. Now we are south of Rome.”