The Kremlin Uses Registered Cossacks as a Means of Stealth Mobilization

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 20 Issue: 155

By:

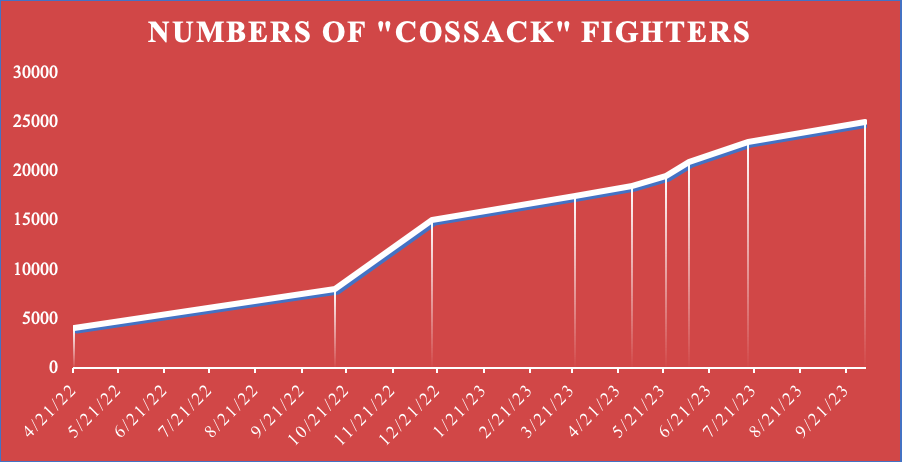

The number of registered “Cossacks” involved in the “Special Military Operation” (SVO) in Eastern Ukraine has risen to 25,000, taking into account rotations and leaves. This number was mentioned in announcements at the All-Russian Forum “Cossacks in the North Caucasus: Current Stage and Image of the Future” at Pyatigorsk State University in Stavropol. On behalf of the Ataman (head) of the “All-Russian Cossack Society,” Nikolai Doluda, First Deputy Konstantin Perenizhko led a roundtable on the role of the “Cossacks” in the SVO. He noted, “more than 25 thousand ‘Cossacks’ of Kuban, Don, Terek, Crimea, the Volga region, Transbaikalia, Siberia, and the Far East—as part of 18 ‘Cossack’ BARS (Combat Reserve Forces) battalions, who took and are taking part in the special operation—voluntarily and without summonses gathered ‘for the ribbon’ [referring to the Ribbon of Saint George, a prominent military symbol heavily associated with the war effort at present]” (Vsko.ru, October 3). The registered “Cossacks” have been one of the most constant components of the Russian forces, and their numbers have steadily risen over time, as demonstrated by Figure 1 below.

The graph demonstrates that not only have the numbers of “Cossack” troops been rising over time, but the trend has also become more pronounced, rising further in late 2022; the number of registered “Cossack” troops remains high today as compared with the start of Russia’s war. In other words, “Cossacks” are making up a larger component of Russia’s forces. Possible reasons for this include the need to replace forces lost after the abortive coup of Yevgeny Prigozhin and Putin’s reluctance to issue a second general mobilization, thereby issuing one by stealth instead. In the latter case, the registered “Cossack” voiskas (troops) represent a vehicle through which more men, both young and not so young, can be paid to “volunteer” to fight.

BARS is the Russian acronym for the Combat Reserve Forces, equivalent to the US Army Reserve or the British Territorial Army. The BARS system was created in 2015, although it remained small in scale until 2021, when the Kremlin began engineering its rapid development. The volunteers are useful both as troops—although they are often given the worst equipment, limiting their effectiveness—and as evidence for the Kremlin’s claim that the war is genuinely popular with ordinary Russians (Themoscowtimes.com, January 15; Bars2021.tilda.ws, October 10). Definitive information is hard to find, but there are rumored to be 32 BARS battalions, which would imply that over half (18) are “Cossack” battalions. Moreover, there is a good degree of overlap between members of private military companies (PMC) and such “Cossack” groups, with the leader of the relatively new PMC “Konvoy,” Konstantin Pikalov, having connections both to “Cossack” groups and to Wagner itself (Roscompromat.com, August 15). There has been speculation over how the Kremlin will replenish its forces in the absence of Wagner. Such “Cossack” organizations provide a ready alternative, as well as vehicles for continuing the service of Wagnerites. This is even more the case now, given that the definition of “Cossack” has changed over time. It is not limited simply to those claiming heritage anymore, but to become an “asphalt Cossack” (as the imitators are known sardonically), one simply needs to don a hat and proclaim a desire to serve the state.

It is true that the number of registered “Cossacks” has been in decline for a while. A post from July claimed their numbers are down, from 506,000 in 2014 (Jolanta Darczewska, 2017, Putin’s Cossacks. Just Folklore- or Business and Politics? Warsaw, Point of View) to 146,000 today, of whom 29,000 are students, and 58,000 are over 60 (Vsko.ru, July 3). This still leaves 60,000 of “prime” fighting age, making them potentially the largest known semi-autonomous armed formation in Russia’s war effort. Drilling down further into the composition of Perenizhko’s claims about the battalions, Doluda previously claimed that there are three battalions each from the Kuban and Terek hosts, two from Don, one from Orenburg, one Orenburg-Volga combined battalion, one from the Ussuriskiy host, one from the Zabaykalsky host, and one from the union of “Cossack” warriors from abroad (Vsko.ru, June 7). Assuming Perenizhko’s claims are correct, two new battalions have, therefore, been created in the last three months, further illustrating the explosive growth of this military organization—and its potential utility in the SVO.

Indeed, Doluda has been exhorting regions to do more to bolster the “Cossack” infrastructure and contribute more men to the ongoing war in Ukraine. For example, his recent complaint that “today, about 9 million people live in the 16 regions where the Siberian voiska is stationed. That voiska is composed of a little more than 8000 ‘Cossacks’ … Why are there so few people in the Siberian voiska? Because representatives of the regional and municipal authorities ignore the ‘Cossacks’ and do not see them as a resource!” (Vsko.ru, September 25). The post continues to outline ways in which the “Cossack” presence in Siberia will expand, including the development of “Cossack” youth organizations and educational institutions, ensuring more young men sacrifice their lives for Putin’s meaningless cause. The “Cossacks” are thus playing and will continue to play an important role in Russia’s stealth mobilization.