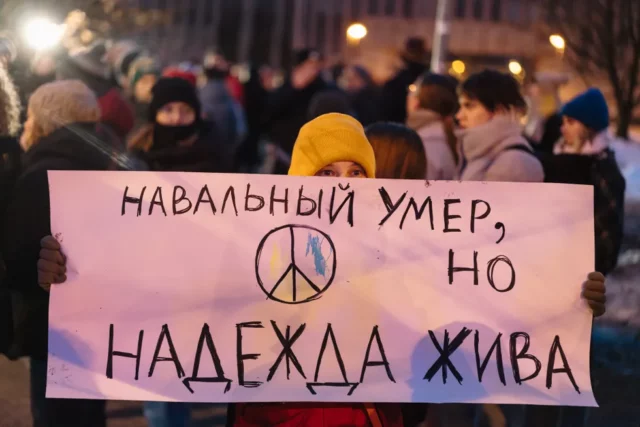

The Russian Opposition After Navalny’s Murder

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 21 Issue: 53

By:

Executive Summary:

- Alexei Navalny’s death and the specter of increased hopelessness in Russia’s regions have highlighted growing apathy among the Russian opposition.

- Supporters of “post-Russia” movements are searching for alternatives to Putin’s Kremlin that differ significantly from the long-standing Moscow-centrist model.

- The next Kremlin crisis may lead to the emergence of a consolidated interregional movement that the authorities struggle to put down, especially if Navalny’s movement and the post-Russia forums cooperate more closely.

Vladimir Putin’s latest “re-election” is seemingly pushing opposition forces in Russia to grow more apathetic. According to official data, Putin won more than 87 percent of the vote, securing his hold on power until at least 2030 (see EDM, March 19, 25). Some in Russian society worry that this development signaled the death knell for any real political change in Moscow. This picture of increased hopelessness is especially prevalent in the various regions. Today, each region is controlled by Kremlin-appointed governors who provide maximum support for the war against Ukraine and mobilize local residents for that purpose. The mass civil protests of recent years—Shiyes (2018–20) and Khabarovsk (2020)—now seem impossible due to the increased level of repression. The January protests in Bashkortostan were suppressed with particular brutality, and the persecution of activists continues (see EDM, February 27; Idelreal.org, March 18). For example, the Russian authorities want to increase the prison term for former head of the late Russian oppositionist Alexei Navalny’s Ufa headquarters, Lilia Chanysheva, to 10 years (Svoboda.org, March 21). Such prison terms have become familiar in today’s Russia, particularly after Navalny’s death in February, as the Kremlin seeks to squash any domestic opposition to Putin’s rule and his war against Ukraine.

Navalny, at one time, managed to create an anti-Putin movement connecting thousands of people, mainly youth, from Russia’s many regions. At the height of his 2018 presidential campaign, Navalny’s team had set up 81 regional headquarters, more than any other officially registered candidates. With the idea of a “Beautiful Russia of the Future” that would not be opposed to the outside world but integrated with it, Navalny brought about a 21st-century wave to Russian politics (Re-Russia.net, February 19). The oppositionist’s supporters did not consume the Kremlin’s television propaganda. Instead, they freely searched the Internet for information, which posed a danger to the Putin regime. It is no coincidence that thousands of websites and popular social networks have been blocked in Russia in recent years.

Navalny’s return to Russia in 2021 was a fatal action. He seemingly did not account for the rapid evolution of the Putin regime toward a totalitarian dictatorship. The state of affairs in 2021, when Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation was banned, sharply contrasted with his regular visits to regional headquarters in mid-2020 (Meduza, April 16, 2021). As demonstrated by the Federal Security Service’s (FSB) attempted poisoning, Moscow would do almost everything in its power to keep Navalny from freely engaging in politics (The Moscow Times, June 9, 2021). As a person who masterfully used the media to spread his message, Navalny would likely have remained an effective politician even from abroad. His ongoing influence, over time, may have contributed to a change in consciousness for Russians. Navalny’s imprisonment immediately upon returning to Russia and his subsequent death in an Arctic penal colony, however, represented a victory of the past over the future.

Today, many of Navalny’s supporters believe that Russia’s future died with him. Such is the personalistic nature of Russian politics—political movements, even in opposition, are usually built around a single leader. Navalny’s closest associates regularly referred to him as an “alternative to Putin” while asserting the need for Moscow-centrism in Russian governance (Region.expert, June 17, 2022). Navalny himself actively advocated for regional governments to become more empowered. Yet, despite his sympathy for regional self-governance, Navalny did not call for a new federative agreement built on equal political standing for the various regions. Federalism remained predominantly economic for him: Moscow should stop robbing the regions and allow them to allocate significant taxes for regional uses.

The same predominantly economic understanding of federalism is demonstrated by other activists from Navalny’s inner circle, including Fyodor Krasheninnikov and Vladimir Milov (4freerussia.org, accessed April 7). Their “normal Russia” project still appears to call for political centralization. If Navalny’s movement follows this path after his death, it will cease to differ from other emigrant “all-Russian” movements that have extremely weak influence over the real situation in Russia’s regions.

At one time, representatives from Navalny’s various regional headquarters put forward political programs for local self-government (Region.expert, July 30, 2020). Today, under pressure from Moscow, these plans have folded. Navalny’s team, nevertheless, has significant experience working for public initiatives on the ground in their respective regions, especially from 2018 to 2021. Tapping back into this grassroots experience will be critical if the movement hopes to avoid a similar fate to its leader.

Many members of Navalny’s regional headquarters are now in political exile (BBC News Russian, July 7, 2021). It is extremely dangerous for them to remain in Russia as they could be imprisoned under the same terms as Chanysheva in Bashkortostan. Various regionalist movements are also active among the Russian émigré communities, holding “post-Russia” forums since 2022 (Svoboda.org, January 4; see “Russia’s Rupture and Western Policy,” accessed April 7). On the one hand, many of these organizations’ ideas for the de-imperialization and demilitarization of Russia are much more radical than those of Navalny’s team. On the other hand, they are more “virtual”—they can proclaim manifestoes of independence from abroad but struggle to spread their ideas within Russia itself. For an independence movement to become more legitimate and recognized by the outside world, it needs to be based on the decision of a freely elected regional government. Today, however, there are no free elections in Russia.

Former representatives of Navalny’s regional headquarters and supporters of “post-Russia” projects could find common ground and jointly develop a real alternative to Putin’s Kremlin. Such an approach would differ significantly from the usual Moscow-centrist templates, which strive to replace the “bad” tsar with a “good” one. “Beautiful Russia of the Future” would take on new meaning—not as some “empire of goodness,” but as a voluntary agreement between self-governing regions.

By persecuting those who advocate for regional self-government, the Russian Federation has clearly demonstrated that it is not a federation at all (Rambler.ru, December 15, 2023). As for Navalny’s movement, if the Kremlin declared the fight against corruption as “extremism and terrorism,” this clearly reveals the true intentions of the Russian state (Vedomosti.ru, August 10, 2021). It also explains why Moscow remains powerless in the face of real terrorism, as shown by the tragic events at Crocus City Hall (see EDM, March 26, 28, April 1). So-called “Black Swan” events regularly occur in Russia, and the next Kremlin crisis may very well lead to the emergence of a consolidated interregional movement that Moscow’s security forces cannot put down.