The Sadr-Sistani Relationship

Publication: Terrorism Monitor Volume: 5 Issue: 6

By:

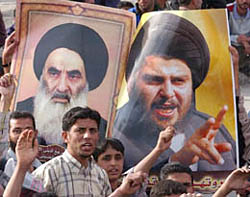

One of the oddest developments in the recent history of Iraq has been the growing connection between the young firebrand cleric, Moqtada al-Sadr, and the highest-ranking Shiite cleric, Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani. Earlier in 2003, the erratic politics of al-Sadr, with his mix of Arab nationalism and militant chiliastic ideology, was considered to eventually collide with al-Sistani’s quietist form of Shi’ism, which advocates that clerics should maintain a clear distance from day-to-day state politics. Since 2004, however, an unlikely alliance has gradually taken form between the former adversaries, which is bound to reshape Iraqi Shiite politics in the years to come.

By and large, the relationship between the two clerics has been one of asymmetrical partnership, in which al-Sistani plays the superior partner, guiding the younger and less experienced al-Sadr in his quest for becoming a legitimate leader of the Iraqi Shiite community. In doing so, al-Sistani has tried to tame al-Sadr by bringing him into the mainstream Najaf establishment in order to form a united Shiite front against extremist Sunnis and the United States. In return, al-Sadr, who lacks religious credentials, has been using al-Sistani’s support to legitimize his religious authority and expand his influence in southern Iraq. The relationship is mutually opportunistic, but also pragmatic, since the two clerics have not been able to ignore each other.

In broad terms, such an alliance signals two significant changes: first, a dramatic shift in the balance of power in Shiite Iraq in terms of the revival of the Hawza, as a cluster of seminaries and religious scholarly institutions in Najaf, and, second, an increase of tension between Shiites and Sunnis in Iraq. Moreover, the growing alliance between al-Sadr and al-Sistani also underlines another vital feature tied to the Shiite ascendancy in Iraq: the rise of Iran as a regional power. Iran has been playing a crucial role in the shaping of Sadr-Sistani relations, since any alliance between Shiite leaders is intertwined with the Qom-Tehran nexus and Iranian politics in the greater Middle East.

Against the Najaf Hawza: 2003-2004

Since the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq, the Sadrist movement, mainly dominated by Moqtada al-Sadr, has emerged as one of the most populist and grassroots currents in the post-Baathist era. Yet the militant movement has also posed the most serious threat to clerical orthodoxy and its conservative and quietist tradition, best embodied by Ayatollah al-Sistani.

Much of the “heterodoxy” of the Sadrist movement lies in its early (2003–04) rejection of clerical monopoly, led by some young clerical students and followers of al-Sadr who accused al-Sistani of transforming the shrine city of Najaf into a “sleeping house of learning.” The heretical tendencies of the Sadrist movement entailed rejecting the religious authority of a living, high-ranking cleric in favor of the rulings of a deceased marja (religious scholar), a blasphemous idea according to the orthodox thinking that al-Sistani and his Hawza represent. Yet there is also the factor of Arab nationalism. Ideologically, the Sadrists are Arab nationalists and resent the presence of any non-Arab cleric in Iraq, especially those of Iranian descent, like al-Sistani, who have been residing in the shrine-cities for decades.

The origin of the movement dates back to the early 1990s, when Ayatollah Muhammad Sadeq al-Sadr, the father of Moqtada, led an anti-quietist campaign by accusing al-Sistani and other leading clerics in Najaf of abandoning ordinary people and allowing Baathist oppression to take place [1]. When Moqtada emerged as the leading figure in the movement four years after the assassination of his father by Saddam’s regime in 1999, he continued his father’s legacy and expanded his anti-quietist movement in the slums of Baghdad and southern Iraq. In spring 2003, al-Sadr refused to accept al-Sistani’s leadership, and declined his invitations for a meeting [2]. Tensions between the outspoken al-Sadr and the quietist al-Sistani were at their highest when the cleric followers of al-Sadr criticized the grand ayatollah for his Iranian origin and even urged him and other quietist clerics to leave Iraq [3]. The conflict between al-Sadr and al-Sistani culminated in the August 2004 showdown between the Mahdi Army and U.S. troops in Najaf, when al-Sistani saw the clash as an opportunity for the eradication of his young rival [4].

Nevertheless, eventually al-Sistani decided to intervene and offer protection to al-Sadr and his followers. After three weeks of intense fighting between the Mahdi Army and U.S. and Iraqi forces around the Imam Ali Mosque in Najaf, al-Sistani was finally able to broker a cease-fire deal with al-Sadr in late August 2004 [5]. Although his change of position was partly aimed at ending the destruction of the shrine complex and protecting Najaf’s inhabitants, al-Sistani saw the Mahdi Army as a major asset in dealing with anti-Shiite Sunni groups and U.S. forces in Iraq. Due to the encouragement from Hezbollah and Tehran, the agreement signaled an opportunity to tame al-Sadr and his Mahdi Army, militarily weakened by U.S. forces, by bringing his troops closer to the mainstream Shiite establishment [6].

Post-2005 Elections and the Iran Factor

The 2004 deal signaled a tipping point in Sadr-Sistani relations, bringing the two leaders closer together with the aim of advancing Shiite interests in the democratic arena. Despite a period of tension with the Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution in Iraq (SCIRI) and the Badr Organization, the largest Shiite militia that backed al-Sistani, al-Sadr finally joined forces with a Shiite-led political party approved by al-Sistani, the United Iraqi Alliance (UIA), in the December 2005 elections. The move advanced a new stage in Sadr-Sistani relations, which underlined how the two clerics saw the importance of a centralized democratic government as a means to solidify Shiite power in a country with a long history of Sunni-dominance.

Since 2004, al-Sadr and al-Sistani have met a number of times to discuss issues related to elections, including a major meeting in mid-September 2004 that included Abdul Aziz al-Hakim, al-Sadr’s main rival [7]. In early September 2004, in a potentially explosive incident, al-Sistani helped al-Sadr by asking the Iraqi police to end the siege of his office in Najaf [8]. Al-Sistani’s growing relations with al-Sadr continued to evolve when he appealed to Abdul al-Saheb-e al-Khoei to delay the search for his slain brother, Sayyid Abdul Majid al-Khoei, who was allegedly murdered by al-Sadr’s followers in 2003 [9]. This was a major move by al-Sistani since it basically extricated al-Sadr of any wrongdoing in the case of al-Khoei’s murder.

After the January and December 2005 elections, al-Sistani refused to call for the disarming of the Mahdi militia. This decision was made in connection with the rise of sectarian tensions unleashed after the bombing of the Shiite al-Askari Shrine in Samarra in February 2006. With the absence of a strong centralized government in Baghdad, al-Sistani considered al-Sadr’s militia as a major force to protect the Shiite community and its sacred shrines against Sunni extremist attacks. He even used al-Sadr to negotiate with the Sunni clerics about the looming problem of sectarian violence. After a major meeting in March 2006, al-Sistani dispatched al-Sadr to discuss the escalation of Sunni-Shiite tensions with a number of Sunni clerics at the Azamiyah mosque in Baghdad [10]. At this stage, al-Sistani appeared to have gained considerable influence over al-Sadr, while his Mahdi Army was gradually breaking into subgroups, challenging their former leader for his compromising stance toward the Sunnis and the Americans—perhaps partly due to al-Sistani’s influence.

In an important meeting in early January of this year, al-Sistani persuaded al-Sadr to end his boycott of the UIA and return to the parliament [11]. Al-Sadr agreed, and his followers returned to the parliament later that month. In another major meeting mid-February, al-Sadr sought the counsel of al-Sistani about attacks and death threats he was receiving from his own militia [12]. Following al-Sistani’s advice, al-Sadr reportedly left Iraq for Iran and he is now staying at his cousin’s house, Jafar al-Sadr, in Qom [13]. This final meeting highlights the growing dependence of al-Sadr on al-Sistani’s religious and intellectual authority, which has increased considerably since the toppling of Saddam’s regime. For now, al-Sistani appears to have tamed al-Sadr, especially by helping him in becoming a major figure to advance an anti-sectarian platform.

Both al-Sadr and al-Sistani share the common interest of protecting the Shiite community against the ongoing sectarian war and, simultaneously, promoting a unified Iraq governed by a centralized government in Baghdad. In this sense, the two are against a federalist system of government, particularly the sectarian-provincial model of federalism advocated by Abdul Aziz al-Hakim. This common objective has brought them closer together, while facing opposition from pro-federal factions, such as the Iranian-backed SCIRI, which continue to push a sectarian agenda in the revised version of the constitution expected to be proposed by the constitutional committee in mid-May 2007.

Here the role of Iran in the making of such an alliance should not be ignored. Although al-Sadr and al-Sistani do not want Iranian influence in Iraq, they also realize that Tehran cannot simply be ignored. Both clerics recognize that Shiite empowerment in Iraq can only be ensured by Iranian support, and challenging Tehran could only lead to the consolidation of Sunni power, with the backing of the United States, in Iraq and the region.

Given the fact that the financial center of his religious network is based in the Iranian city of Qom, al-Sistani has been careful not to upset the Iranian authorities. He refuses to challenge the authority of Ayatollah Khamenei, despite their differences in theological outlooks. For instance, al-Sistani has so far declined to declare a fatwa on the production of a nuclear bomb since he wants to avoid a confrontation with Tehran [14]. Al-Sistani has also criticized the student reformist movement in Iran for its disregard of Iranian national interests and warned the students against foreign influences [15]. He has even praised the Iranian president, Mahmud Ahmadinejad, for his travels to local regions in Iran and getting involved in the daily problems of his constituency; he has urged Iraqi officials to follow in Ahmadinejad’s footsteps in Iraq [16]. Like al-Sadr, al-Sistani considers the backing of Iran as something necessary in a period of foreign aggression (i.e. Israel and the United States) and increasing anti-Shiite currents in the Sunni world. Iran, too, recognizes the influence of the Najaf Hawza and the Sadrists in Iraq, and continues to ride the rising tide of the Shiite revival. Tehran knows that al-Sadr and al-Sistani can play a major role in advancing Iran’s interests in Iraq and the region in case the United States decides to attack Iran’s nuclear facilities.

Implications of Sadr-Sistani Ties

The changing relationship between Moqtada al-Sadr and Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani signals a dramatic shift in the political landscape of the Shiite Iraqi community since the fall of the Baathist regime in 2003. While new conflicts have emerged between Shiite groups, especially between the opposition groups that left the country (Dawa and SCIRI) and those who stayed in Iraq under Saddam’s reign (Sadrists), old adversaries are now becoming new partners as a result of the sectarian conflict engulfing the country.

There are two main implications involved. First and foremost, despite theological and ideological differences between Shiite groups and leaders, sectarian identity is playing a major role in the shaping of future alliances and conflicts in Iraq. It is an undeniable truth that with the rise of Salafi Sunni attacks against Shiites, rivalry among Shiite groups subsides, and loose alliances are formed to protect the community. Yet while creating such alliances, each rival group also prepares to protect its own particular economic and political interests in various localities throughout Baghdad and southern Iraq [17]. In short, Shiite relations in Iraq should be considered as both political and sectarian. Theological and ideological differences play an important role, but not a prominent one, as Sadr-Sistani relations best demonstrate.

Such a dramatic shift, however, also underlines the unpredictable political situation in the country, signaling certain unforeseen challenges that may arise in the years to come. In this sense, it is hardly an overstatement to claim that with the death of Ayatollah al-Sistani, who is 76, new unforeseen problems will likely emerge in the form of competition among leading Shiite groups to control the Shiite community. Since the grand ayatollah has not yet appointed a successor according to the traditional clerical succession process, it remains unclear what sort of political vacuum his death could create. Nevertheless, a political vacuum will certainly be created. No other cleric in the post-Baathist era has had so much authority in Iraq, and it is very likely that his absence will be deeply felt.

The leading candidate to replace al-Sistani is the Afghan-born, Najaf-based Grand Ayatollah Muhammad Ishaq al-Fayadh. He is an old seminary student friend of al-Sistani since the 1950s and a staunch ally since 1992. Ayatollah al-Khoei, the mentor of al-Sistani, reportedly recognized al-Fayadh as one of his most trusted and loved students, and it is likely that al-Sistani will soon appoint him as his successor. As a successor, al-Fayadh is more likely to deal directly with the United States and get involved in the transition process; however, he is also likely to antagonize the Sadrist nationalists, who view him as an Afghan foreigner who should not have a say in Iraq’s politics. Two other Najaf-based clerics, the grand ayatollahs Bashir Hussein al-Najafi and Muhammad Said Hakim, are also potential candidates. It is unlikely that they will be the successors, however, because they are considered lesser scholars than al-Fayadh, who is highly respected by many Shiite Iraqis, particularly by the tribal chieftains of Najaf.

With the vacuum of authority in Najaf, new conflicts between Shiite groups will certainly come to light, especially in the oil-rich province of Basra, where SCIRI and the Sadrists, especially the Fadhila Party, compete for territorial control. With spawned rivalries among various Shiite groups (and subgroups), Iraq may also see an increase of sectarian conflict as anti-Shiite Salafi groups begin to increase their attacks on Shiites with the aim of creating more chaos in a community devoid of a central religious authority. Tehran can also extend its religious network in Najaf in order to establish the authority of Ayatollah Khamenei in the Najaf Hawza [18]. Khamenei’s increase of influence in southern Iraq could seriously jeopardize the independence of the Hawza. These scenarios could also cause major problems for a transitional government in Baghdad that is seeking to establish authority in southern Iraq.

Therefore, what are the implications of a Sadr-Sistani partnership? First and foremost, the United States should be aware of the unpredictable politics of the Shiite community. The swing of alliances merits serious attention, despite the fact that sectarian identity will play a central role in the intra-Shiite relations in years to come. Second, the United States should also recognize the enduring authority of the Najaf Hawza and its sphere of influence in Shiite Iraq. This influence is so significant that even the defiant al-Sadr failed to challenge the establishment, let alone muster enough support to lead the Shiite community among the poor and the youth for his anti-occupation and nationalist image.

It was the common consensus in the academic and policy communities that after the Samarra bombing of 2006, al-Sistani had become a marginal figure. Despite his brief diminishing influence as a result of the rise of sectarian tensions, al-Sistani now appears to be back with even greater authority. He is supported by centuries of traditional authority and backed by an extensive financial and religious network that reaches beyond Iraq and Iran. Both Tehran and al-Sadr know that al-Sistani should not be ignored. The United States should certainly do the same.

Notes

1. International Crisis Group, Iraq’s Muqtada al-Al-Sadr: Spoiler or Stabilizer? p. 3-6.

2. Ibid.

3. Author interview with an al-Sistani representative, Najaf, Iraq, August 7, 2005.

4. Vali Nasr, The Shi’a Revival: How Conflicts within Islam Will Shape the Future, New York: Norton, 2006, p. 194.

5. According to al-Sistani’s representative in Najaf, Hamed Khafaf, the deal also included the disarming of the Mahdi Army, Baztab, “Moafeqat-e Moqtada va Dowlat-e Moaqat ba Pishnahade Ayatollah al-Sistani,” September 3, 2004, https://www.baztab.com. The disarmament of the militia was never fully enforced.

6. Author interview with an al-Sistani representative, Najaf, Iraq, August 7, 2005. See also Vali Nasr, p. 194.

7. Baztab, “Jalas-e Moshtarak-e Hakim va Moqtada al-Sadr ba Ayatollah al-Sistani,” September 15, 2004, https://www.baztab.com.

8. Ibid.

9. The reason behind this call was mainly to show Shiite solidarity in the January 2005 elections. See Baztab, “Inetaf-e Marjayat Shi’I dar Moqableh Al-Sadriha baraye Vahdat-e Shiaan-e dar entekhabat,” November 12, 2004, https://www.baztab.com.

10. Baztab, “Didar-e Moqtada al-Sadr va Ayatollah al-Sistani,” March 29, 2005, https://www.baztab.com.

11. Hussain al-Kabi, “al-Sadr Yahath Mowaqf al-tiyar al-Sadri beshan al-Hukumat wa al-barleman ma al-Sistani,” al-Sabaah, January 9, 2007.

12. Al-Sistani is reported to have advised al-Sadr the following: “You have two options: bear the consequences, on you and the Shiites in general, or withdraw into a corner,” Rod Nordland, “Silence of the Sadrists,” March 12, 2007, Newsweek, p.38.

13. Reported by Diyar al-Umari on al-Arabiya TV, February 19, 2007.

14. Author interview with a seminary student of al-Sistani in Qom, Iran, December 23, 2005.

15. Abdul al-Rahim Aghiqi Bakhshayeshi, Faqihe Varasteh, Qom: Novid Islam: 2003, p. 202.

16. Baztab, “Ayatollah al-Sistani: Az Amalkard Ahmadinejad Ulgo Begirid,” November 11, 2006, https://www.baztab.com.

17. The case of Sadrist and SCIRI relations since 2003 merits serious attention.

18. The control of Najaf has been one of the primary objectives of the Iranian government in Iraq since the fall of Saddam’s regime in 2003. In the last four years, Ayatollah Khamenei has established a center in Najaf, which pays the highest salary to the seminary students in the city. The extent of Tehran’s influence in Najaf, however, is still limited, as al-Sistani and three other high-ranking clerics remain the most revered and influential religious authorities in the shrine city.