The Security Component of the BRI in Central Asia, Part Two: China’s (Para)Military Efforts to Promote Security in Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan

The Security Component of the BRI in Central Asia, Part Two: China’s (Para)Military Efforts to Promote Security in Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan

Introduction

Successfully realizing the ambitions of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) will require the People’s Republic of China (PRC) to guarantee the protection of its workers, businesses, and critical infrastructure in BRI countries. The first part of this short series of articles discussed Beijing’s general views on the security challenges to PRC interests in Central Asia (China Brief, July 15). This second article is concerned with two specific cases: Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. Following the break-up of the Soviet Union, these two states remained heavily dependent on Russia in terms of economics and security (Ipg-journal.io, April 8). However, China’s increasing influence has now created a state of “competitive cooperation” between Beijing and Moscow.

Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan occupy key strategic territory for Beijing’s interests in Central Asia, as seen in their proximity to the potentially rebellious Xinjiang region; their importance for transportation infrastructure projects linked to the BRI; and the strategic location of the Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Region (戈尔诺-巴达赫尚自治州, Ge’ernuo-Badaheshang Zizhizhou) of eastern Tajikistan, which covers most of the territory connecting the PRC to Afghanistan. For Beijing, the successful projection of influence over these two countries, and their internal stability, are key conditions for the successful completion of BRI projects further afield in Central Asia.

Tajikistan: China’s Anti-Terrorist Stronghold in Central Asia?

Chinese interests in Tajikistan are based on two interrelated elements. The first of these are geo-economic calculations, in which Tajikistan is viewed as an essential part of the “Quadrilateral Cooperation and Coordination Mechanism”—a framework established in 2016 consisting of China, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, and Pakistan—intended to grant China access to the Indian Ocean (PRC Ministry of Defense, August 28, 2017). The second of these are security-related concerns, which Beijing sees as connected to the so-called “Three Evils” (or “Three Forces”) (三股势力, San Gu Shili): terrorism (恐怖主义, kongbu zhuyi), separatism (分裂主义, fenlie zhuyi), and extremism (极端主义, jiduan zhuyi). Tajikistan occupies a key buffer region for China, and is seen as an integral part of these concerns (China Brief, July 15).

In June 2019, Chinese Communist Party (CCP) General Secretary Xi Jinping and Tajikistan President Emomali Rahmon agreed to further deepen the two countries’ “comprehensive strategic partnership,” which included strengthening bilateral cooperation “in combating the ‘three forces’… as well as transnational organized crimes [and] cyber security” (Xinhuanet, June 16, 2019). Chinese concerns related to the situation in Tajikistan, and potential repercussions for the BRI, have been amplified by reports that around 400 militants—associated with ISIS, Jamaat Ansarullah, and the Turkistan Islamic Movement (TIM)—have attempted to establish a new terrorist base on the territory of the GBAO (Stanradar, April 23, 2020).

Fortifying Tajikistan’s Physical Infrastructure

To effectively deal with these challenges, Beijing is relying on four main pillars. The first of these is fortifying Tajikistan’s physical security infrastructure. The logic of creating military infrastructure in Tajikistan has been summarized by Beijing-based military expert Li Jie, who noted that if Chinese forces wish to “eliminate the so-called three forces, they need to go to their power bases and take them down. But since the PLA is not familiar with the terrain… bilateral cooperation is the best way to get win-win results” (SCMP, August 28, 2018). The foundation for this policy was set in October 2016, when Beijing and Dushanbe reached an agreement on modernizing security infrastructure in their border region, which reportedly included plans for 11 “outposts of different sizes” and a training center for border guards (Belt and Road News, February 26, 2019)

China’s Direct Security Presence

The second pillar is the direct presence of Chinese forces in the country. Tajik authorities have repeatedly denied “rumors” regarding the existence of Chinese military bases in the country (Asiaplustj.info, February 21, 2019). However, in the Murghob District of the GBAO, a Chinese military base—officially, a Tajik base built to protect Chinese investments—has been operating for at least four years (Centralasia.media, February 20, 2019). Locals have claimed that several hundred Chinese soldiers have been deployed at the base (Currenttime.tv, February 19, 2019). Further investigations have revealed that the “Chinese soldiers” are in fact representatives of the Chinese People’s Armed Police (中国人民武装警察部队, Zhongguo Renmin Wuzhuang Jingcha Budui), or PAP. The paramilitary PAP is responsible for internal security, riot control, antiterrorism, disaster response, law enforcement, and maritime rights protection (Gov.cn, August 27, 2009), and operates as a rough analogue to Russia’s National Guard (Carnegie.ru, March 25).

Combined Training and Military Assistance

The third of Beijing’s pillars consists of training and military support. This is intended to serve a dual purpose: in addition to dealing with Islamic militants, it also increases China’s influence in the country. This is especially the case given the state of Tajikistan’s economy, and the near-complete collapse of its armed forces and defense industry after 1991 (Dfnc.ru, 2019). According to local analysts and military experts, Tajik military capabilities are still inadequate for the range of challenges faced by the country, and therefore require foreign assistance (Stanradar.com, February 25, 2020).

The intensification of Chinese-Tajik military cooperation reached another landmark in 2016, when combined military exercises (involving 10,000 men) were held in the Pamirs region, in the Ishkashim district of the GBAR (Riss.ru, April 22). Three day military exercises were repeated in the same area in 2019 (CANN, April 21), which led some international observers to comment that Dushanbe was “increasingly outsourcing its security needs to Beijing” (Eurasianet.org July 9, 2019). Furthermore, among Central Asian states Tajikistan is the largest recipient of uncompensated Chinese military aid, which now also extends to matters such as the construction of military facilities and apartments for Tajik military officers (President.tj, May 5, 2016).

The fourth of Beijing’s pillars for increasing security (and its own influence) in Tajikistan is the use of private security companies (PSCs), a phenomenon likely to grow in significance as China’s BRI projects continue to expand throughout the world. As noted by Lu Guiqing, general manager of the Zhongnan Group Corporation: “[W]hen you ‘go out’ safety is the most important” (SCMP, April 24, 2017). While there is no firm evidence to indicate that Chinese PSCs are currently operating in Tajikistan, analysis of the Chinese PSCs industry points to China Overseas Security Group (中国海外保安集团, Zhongguo Haiwai Bao’an Jituan), Frontier Services Group (先丰服务集团, Xianfeng Fuwu Jituan) and G4S (杰富仕, Jiefushi) as the enterprises best suited for deployment to the country (China Brief, May 15).

In light of a controversial 2011 agreement that reportedly put 1 percent of Tajik territory under de facto PRC control, as well as huge financial debts owed by the Tajik government, Beijing has significant opportunities to boost its military and paramilitary presence in the country—which in turn will open up valuable inroads to Afghanistan (Vesti.kz, October 4, 2011).

The PRC’s Security Interests in Kyrgyzstan

The range of challenges faced by China in Kyrgyzstan is similar to those found in Tajikistan. The prospects of terrorism and public unrest are the two main challenges faced by the Chinese in the country; to which must also be added anti-Chinese sentiment, which is sometimes accompanied by violence (Forbes.kz, September 18, 2019). The incident with arguably the greatest impact on Chinese security perceptions related to Kyrgyzstan was the 2016 terrorist attack on the Chinese embassy in Bishkek, which vividly exposed the weaknesses of the Kyrgyz security system. As noted by Li Lifan of the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences: “[T]he attack will almost certainly have security implications for many Chinese projects in Kyrgyzstan and other Central Asian nations as they become the new linchpin of the ‘One Belt One Road’ initiative.” Another commentator, Li Wei of the China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations, predicted that security conditions would worsen “[D]ue to collusion between local fundamentalist movements and the exiled Uygur Muslim extremist groups” (SCMP, September 1, 2016).

To deal with these challenges, the Chinese side is likely to rely on two main tools. The first of these consists of exercises and military aid to boost local security capabilities, which were seriously weakened after the dissolution of the USSR. [1] Similar to a parallel effort in Tajikistan, the PRC has sponsored an aid program for the construction of apartments for local military officers (Tj.sputniknews.ru, March 22, 2017). The first combined Sino-Kyrgyz anti-terrorism exercises were launched on October 11, 2002 near the PRC-Kyrgyz–border (the Irkeshtam crossing area), and involved Kyrgyzstan’s border forces and approximately 300 Chinese troops from Xinjiang (China.org.cn, October 11, 2002).

Later, Kyrgyz armed forces anti-terrorism training was placed primarily put under the framework of the Russia-dominated Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO). However, the Chinese have maintained a significant role: between 2003 – 2016, the Kyrgyz military held ten exercises or training events with their Chinese counterparts (Carnegie.ru, March 25), and this has been accompanied by the growth of Chinese military aid (Refworld.org, September 4, 2014). An important milestone was reached in 2019, when a bilateral counter-terrorism exercise titled “Cooperation-2019” was launched at a training base in Xinjiang region, involving members of the PAP and the National Guard of Kyrgyzstan (Xinhuanet, August 7, 2019). [2]

Kyrgyzstan: The Ideal Testing Ground for Chinese Private Security Companies?

The second major tool that the Chinese are likely to employ (or test out) in Kyrgyzstan are PSCs, which are emerging in importance as the BRI expands (China Brief, May 15). Given the lower level of risk in Kyrgyzstan (as compared to neighboring Tajikistan), and the general weakness of Chinese PSCs, Kyrgyzstan offers a promising testing ground for these companies. Voices arguing for the use of PSCs to protect Chinese nationals in Kyrgyzstan became louder after the outbreak of mass protests, accompanied by violence, in the central Naryn Region (Uyghur Congress, January 26, 2019). These incidents revealed explicit anti-Chinese sentiment, and vividly demonstrated difficulties that Chinese businesses have had with protecting their employees and property (Knews.kg, August 26, 2019). In addition to a very harsh official statement issued by PRC officials that demanded improved security for Chinese nationals in the country, Chinese businesses have unofficially asked for permission to employ PSCs (Forbes.kz, September 18, 2019).

Local commentator Mederbek Korganbayev has written that “[I]n the future China might be able to lobby— through the Kyrgyz Parliament—for a law allowing Chinese investors to use PSCs on the territory of Kyrgyzstan.” The author also presumed that the personnel of Chinese PSCs will be equipped with “ordnance weapons as well as special means [spetsredstva]” (Centralasia.news, August 25, 2019). Kyrgyz officials denied these assertions, calling the article “lies” and promising to severely punish those spreading such information (Kaktus.media, August 26, 2019).

However, given overall trends—including the growing privatization of security—this prospect does not seem totally unfounded. One of the largest Chinese state-owned enterprises operating in the country, China National Electronics Import & Export Corporation (CEIEC), has concluded an agreement with the Kyrgyz government regarding public surveillance. According to local sources, cameras and other gadgets could be used by China “for protection of its interests in case of outbreaks of anti-Chinese demonstrations, and provocations aimed against Chinese nationals” (Ia-centr.ru, September 1, 2019).

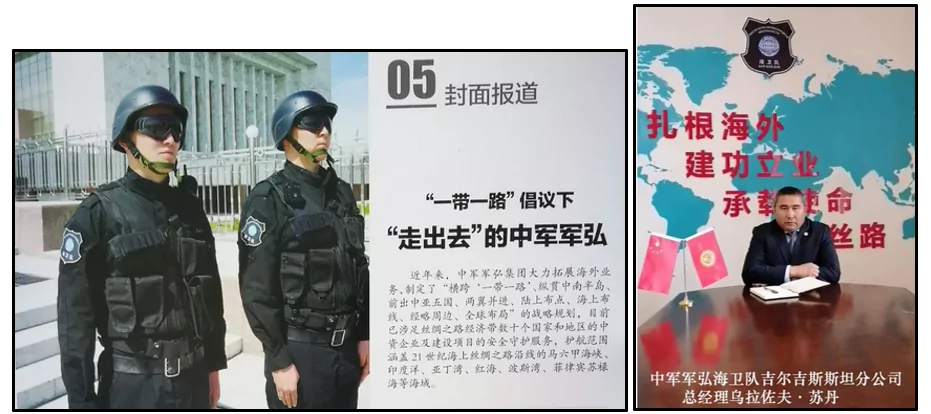

According to some experts, China Railway Group Limited—involved in the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan Railway (CKU) project—relies for security services on Zhongjun Junhong (中军军弘安保集团, Zhongjun Junhonh Anbao Jituan) one of the largest Chinese private security companies, which has had a branch in Kyrgyzstan since 2016 (Mp.weixin.qq.com, April 27, 2019). This PSC has reportedly secured more than twenty Chinese clients in Kyrgyzstan: in addition to China Railway Engineering Group, these clients include Sinohydro, Huawei Technologies, and Sanmenxia Luqiao Construction Group (The Diplomat, July 3, 2019).

According to prominent Russian Sinologist Professor Alexey Maslov, for the time being the PRC is experimenting with building military facilities abroad, and cautious international deployments of its PSCs. However, the Chinese “[A]re not good in either element… [and only after] they have acquired necessary skills…it will be possible to talk about full-fledged large-scale actions” (Afghanistan.ru, February 25, 2019).

Conclusion

Even though China’s security presence in Central Asia has been dwarfed by its economic involvement (SCMP, September 1, 2016), the successful implementation and expansion of the BRI will require Beijing to further invest in maintaining security in the region—and in Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, in particular. This is likely to result in growing discontent among anti-Chinese forces in the region. It is also likely to breed suspicion in Russia, which has for decades exercised a sphere of influence in Central Asian security affairs (particularly, although not exclusively, in Tajikistan). Recent moves by Chinese actors indicate that a longstanding tacit agreement—one which gave the leading security role to Russia, and the leading economic role to China—might be in the process of changing.

Notes

[1] For example, the last military production factory in Kyrgyzstan was effectively closed down in 2013 (Dfnc.ru, accessed July 22).

[2] The PRC has sponsored exercises with Central Asian countries under the names Xiezuo-2019 (协作-2019) and Hezuo-2019 (合作-2019), both of which are usually translated as “Cooperation-2019.”