The Strategic Implications of Chinese-Iranian-Russian Naval Drills in the Indian Ocean

Publication: China Brief Volume: 20 Issue: 1

By:

Introduction

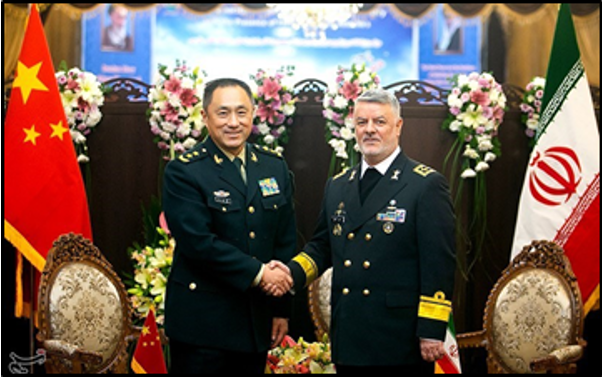

In early December, Major General Shao Yuanming (邵元明), the Deputy Chief of the Joint Staff Department of the Central Military Commission of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), traveled to the Islamic Republic of Iran for rare high-level military meetings. These meetings were held for the purpose of organizing a series of unprecedented joint naval drills between China, Iran, and Russia, which were held in the Indian Ocean and the Sea of Oman from December 27–29. The drills took place just as escalating tensions between the United States and Iran reached a crisis point at the end of 2019. The exercise also signified a deepening relationship between Iran and the PRC in economics, diplomacy, and security affairs.

China and Russia have both increased military and economic cooperation with Iran in the year and a half since the U.S. government pulled out of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). However, while Iran’s government has repeatedly touted its deepening relations with China and Russia as a show of diplomatic strength, its allies have been less public about the growing relationship. In December, Iranian officials lauded the trilateral exercises—titled “Marine Security Belt”—as proof that Iran can outlast crippling sanctions with aid from its non-Western allies, and declared that the drills signaled a new triple alliance in the Middle East (Tasnim News, December 29, 2019). [1] By contrast, officials from Russia and the PRC were more restrained, framing the joint exercises as part of routine anti-piracy operations, highlighting their peacekeeping priorities and seeking to depoliticize the drills (South China Morning Post, September 23, 2019; Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Russia), October 2, 2019).

Participating Vessels and Exercise Activities

The major naval units participating in the exercise were:

- China: Type-052D (Luyang III)-class guided missile destroyer Xining (DDG-117).

- Russia: Neustrashimy-class frigate Yaroslav Mudry (FF-777) was the lead Russian unit. It was accompanied by two smaller auxiliary vessels—the tanker Elnya and the tugboat Viktor Konetsky—from Russia’s Baltic Fleet (TASS, December 26, 2019).

- Iran: Islamic Republic of Iran Navy (IRIN) frigate Alborz (FF-72) was the most prominent Iranian surface unit involved in the exercise. Secondary roles were played by the frigate Sahand; the corvette Bayandor; the hovercraft Tondar; and the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps Navy (IRGCN) vessels Shahid Naserinejad and the catamaran Shahid Nazeri (Mehar News, Dec 29, 2019).

Video and photos of the exercise indicated a series of relatively simple tactical operations, including: live fire drills; an anti-piracy exercise involving Iranian commandos fast-roping onto a surface vessel; a drill to extinguish flames on a burning ship; and a pass-in review of participating naval vessels on the final day (Moscow Times, December 27; Mehr News, December 29; Tasnim News, December 30).

Iran and China Report Mixed Messages on the Trilateral Exercises: A “Golden Triangle” vs. “Routine Exercises”

The Iranian Armed Forces (IAF) flotilla commander in charge of the exercises, Rear Admiral Gholamreza Tahani, said after the drills that “the message of this exercise is peace, friendship and lasting security through cooperation and unity…[and] to show that Iran cannot be isolated” (Mehr News, January 2). An Iranian state television report heralded the drills as signaling a “new triangle of sea power” in the region, and quoted IAF Rear Admiral Hossein Khanzadi’s bold declaration: “Today, the era of American free action in the region is over, and [U.S. forces] must leave the region gradually” (Tasnim News, December 29, 2019). [2]

Notably, Rear Admiral Tahani also discussed collective naval security arrangements, asserting that countries that share security, economic, and political interests should cooperate to restore collective security in the region. He described this as particularly important for what he termed the Indian Ocean’s “Golden Triangle” of strategic straits (the Strait of Hormuz, the Strait of Malacca, and the Bab al-Mandeb), saying: “[N]o single country can guarantee the security of the oceans. For this purpose, a collective effort is needed. To secure the ocean, countries are seeking synergy and convergence while holding joint naval exercises in oceanic waters” (Iran Press Agency, December 27, 2019).

This language contrasted with the more muted tone offered by PRC officials: when PRC Ministry of Defense spokesperson Wu Qian spoke just ahead of the drills, he said that “The joint exercise is a normal military exchange arrangement of the three countries. It is in line with related international laws and practices and has no connection with [the] regional situation” (Xinhua, December 26, 2019). PRC officials also did not explicitly endorse the “Golden Triangle” concept, but they did endorse the idea of new alignments for collective maritime security (see further discussion below). In the same press conference, Spokesperson Wu said, “The naval drills aim to deepen exchange and cooperation among the navies of the three countries, and display their strong will and capability to jointly maintain world peace and maritime security, while actively building a maritime community with a shared future” (CGTN/Youtube, December 27, 2019).

The Deepening Strategic Relationship Between China and Iran

The trilateral drills could be viewed as a step towards deepening Iran’s strategic relationship with China, which until now has been predicated primarily on economic ties. After China’s secondary sanctions waiver expired in May 2019, it continued to buy Iranian oil in defiance of the United States. [3] In July, the United States sanctioned the Chinese oil processing company Zhuhai Zhenrong and its chief executive Youmin Li, and imposed sanctions in late September on other Chinese nationals and entities accused of flouting secondary sanctions on Iran—including two subsidiaries of the Chinese giant COSCO Shipping Corporation (SCMP, July 23, 2019; SCMP, September 26, 2019).

China faced a difficult challenge in balancing its Iranian trade alongside contentious economic relations with the United States, and some Chinese companies decreased their business with Iran after sanctions were reimposed rather than risk blowback (total Chinese exports to Iran declined by close to 40 percent at the end of 2019) (Radio Farda, December 1, 2019). [4] However, the activities of some of China’s largest state-owned enterprises indicated Beijing’s intent to continue purchasing Iranian oil. [5]

Vocal criticisms from the U.S. State Department and unconvincing secondary sanctions have largely failed to deter the PRC, which made promises in the second half of 2019 to dramatically step up its Iranian investments (China Brief, November 1, 2019). Iran’s Foreign Minister Mohammad Zarif and his PRC counterpart Wang Li reportedly signed memoranda this past August that could hallmark major new investments in the Iranian economy (Al-Monitor, September 17, 2019). [6] Iran also granted the state-owned China National Petroleum Company (CNPC) advantageous contracts to develop controlling stakes in some of its largest oil reserves (to include the North and South Azadegan oil fields and the supergiant South Pars gas field), and Chinese dealmakers were able to lock in promises for cheap crude oil and liquid natural gas (LNG) for years to come (OilPrice, December 10, 2019).

China has also long sought to increase its arms sales to the Middle East, and the current situation provides many opportunities to do so. While it is nowhere close to supplanting the United States or Russia (the region’s first and second-largest arms providers, respectively), China has increasingly become an alternative to U.S. arms for many states in the Middle East (China Military Online, September 23, 2019.) During a mid-September visit to Beijing last year, IAF Chief of Staff Major General Mohammad Baqeri said that “Iran attaches great significance to its relations with the People’s Republic of China in all areas. We have long-standing ties in the military sector as well, and hope this visit can be a turning point in the development and reinforcement of [our] relations” (Tehran Times, September 13, 2019). [7]

Trilateral Drills Reveal the Possibility of Competing Collective Security Pacts

A continuing program of Chinese-Iranian-Russian collective maritime security cooperation could pose a challenge to existing U.S.-led initiatives in the Gulf Region. In November 2019, the U.S.-led International Maritime Security Construct (IMSC) began stability and peacekeeping operations in the Arabian Gulf, Strait of Hormuz, the Strait of Bab el-Mandeb, and the Gulf of Oman. [8] IMSC was formed in the wake of a series of suspected Iranian attacks (or seizures) directed against oil tankers—as well as two September 2019 attacks on Saudi oil refineries, which the United States and Saudi Arabia blamed on Iran (Al Jazeera, September 14, 2019). The IMSC will operate out of Bahrain under the leadership of the U.S. Naval Forces Central Command, with members to include Australia, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, the United Araba Emirates, the United Kingdom, and Albania.

Russia had introduced a separate concept for collective security for the Persian Gulf just months before the formation of the IMSC, proposing an international conference that would lead to the creation of a cooperative security organization in the region. Moscow’s proposal included establishing military hotlines for communication, and rejecting the permanent deployment of military forces from states outside the region. Beijing endorsed Moscow’s vision two days after it was presented, stating that such a proposal would benefit “peace and stability in the Persian Gulf region [which] are of utmost importance to ensure safety and development of the region and the world as a whole” (TASS, July 25). If the joint military drills by Iran, Russia, and China signal a nascent maritime cooperative entity in the making, it could create another vector for naval competition between the United States and China in the Indian Ocean.

Conclusion

Under the pressure of sanctions since 2018, Iran has refused to back down in the face of rapidly escalating tensions with the United States, its confidence bolstered in large part by continued economic support from China and Russia. In early December, President Rouhani announced Iran’s 2020 “budget of resistance,” which was predicated on a $5 billion loan from Russia and Chinese promises to massively increase the total oil output of Iran’s energy reserves (OilPrice, December 9, 2019). Iran has repeatedly and overtly framed its deepening relations with China and Russia as the beginnings of a non-Western alliance system that could challenge the U.S.-led international order.

From the Chinese perspective, the relationship is more complex and less ambitious. Chinese diplomats have balanced their continuing engagement with Iran alongside the need to negotiate a complex (and also contentious) Sino-American relationship. While China needs Iranian oil to enable Beijing’s key political priorities of economic growth and domestic stability, the bilateral dynamic is asymmetric: China supplies nearly a quarter of Iran’s foreign trade, while Iranian trade represents only one percent of Chinese imports (Trading Economics, China, Iran, undated). In other words, China does not need Iran in the same way that Iran needs China. China has taken advantage of recent opportunities to invest heavily in strategic projects within Iran, but it has also hedged its bets by engaging with other regional powers. [9]

In light of tensions in the Gulf Region, the December naval drills provided a symbolic military and political show of support from Russia and China for Iran—and also reflected a strategic alignment in the making between the three countries, with an aim to protect their shared strategic interests in the Indian Ocean. Such a powerful trio would be able to exercise greater influence in the Middle East, and would present a challenge to the U.S-led IMSC maritime coalition force. A growing naval competition in the troubled waters of the Indian Ocean between the United States and China could be seen in the near future.

Syed Fazl-e-Haider is a contributing analyst at the South Asia desk of Wikistrat. He is a freelance columnist and the author of several books, including the Economic Development of Balochistan (2004). He has contributed articles and analysis to a range of publications including Dawn, The Express Tribune, Asia Times, The National (UAE), Foreign Affairs, Daily Beast, New York Times, Gulf News, South China Morning Post, and The Independent.

Elizabeth Chen, the Program Assistant for the Jamestown Foundation’s China Brief, contributed additional research and analysis to this article.

Notes

[1] The name of the joint exercises recalls China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), an overarching foreign policy program that aims to “construct a unified large market” that connects overland rail and road transport links, or “belts,” with maritime “roads,” including the “21st Century Maritime Silk Road.” (See: “Vision and Actions on Jointly Building the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road,” Xinhua, 2015, https://www.xinhuanet.com//english/2017-06/20/c_136380414.htm.) In light of widely reported setbacks plaguing the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), some analysts have speculated that China may be turning to Iran as an alternative partner in the Indian Ocean (China Brief, November 1, 2019).

[2] The first day of the “Marine Security Belt” exercises took place just as the U.S.-Iran conflict in Iraq began to escalate rapidly: an American contractor and two Iraqi security officers were killed in an attack on the K1 military base in Kirkuk. The U.S. military attributed the strike to Iranian-backed militias (Rudaw, December 28, 2019). Iran has denied responsibility for the attack. On January 2, a U.S. drone strike killed Qasem Soleimani, leader of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Quds Force. This action ratcheted tensions between the U.S. and Iran to an unprecedented level. At the time of publication, the U.S.-Iran Crisis is still ongoing, with China and Russia watching carefully. See: (Moscow Times, January 3; SCMP, January 3).

[3] The PRC was the largest importer of Iranian crude oil in 2019; the U.S. has estimated that it receives between 50-70 percent of Iran’s oil exports (Reuters, August 8, 2019).

[4] Beijing asked Washington to lift sanctions on COSCO, which is the PRC’s largest shipping company, during trade talks in October. (Bloomberg, October 10, 2019.)

[5] See Note [3].

[6] See also Foreign Minister Zarif’s op-ed in the Global Times, published just ahead of his August visit to Beijing: “Shared Vision binds Iran-China relations,” Mohammad Javad Zarif, August 26, 2019, Global Times, https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1162671.shtml. Foreign Minister Zarif visited Beijing a total of four times in 2019, with his last trip to Beijing taking place after the successful conclusion of Operation Marine Security Belt. Foreign Minister Zarif also visited Moscow before ending the year in Beijing, where he reportedly discussed the trilateral drills and briefed PRC Foreign Minister Wang Yi on Iran’s nuclear situation (Atlantic Council, January 6).

[7] China’s arms sales strategy in the Middle East is guided by its 2016 Arab Policy Paper, which lays out “a new type of international relations” that promotes “win-win cooperation and win-win strategy” (State Council, January 13, 2016). This language has been interpreted as a general focus on defense-oriented sales based on economic motives, not political ones. As one analyst notes: “dealing with China may be an attractive alternative [to the U.S.] that is perhaps less likely to involve political strings, complications, or potential repercussions that typically accompany arms deals with the U.S.” (SIPA, December 3, 2018.)

[8] The operation’s mandate is to “deter malign activity, promote maritime security and stability, and ensure freedom of navigation and free flow of commerce” in the Arabian Gulf, Strait of Hormuz, the Strait of Bab el-Mandeb, and the Gulf of Oman. (US Central Command, July 19, 2019.)

[9] Chinese oil imports from Saudi Arabia (with which it also has a “comprehensive strategic relationship” dating back to 2016) have increased in the last two years (EIA, July 24, 2019). Almost a month before the trilateral naval exercises between China, Iran, and Russia began, the PLA Marine Corps began three weeks of joint exercises in Jeddah with the Special Forces of the Saudi Arabia Royal Saudi Naval Forces (RSNF) (China Military Online, November 20, 2019). The publicly stated missions of Operation Marine Security Belt and Blue Sword 2019 are almost interchangeable: the director of Blue Sword 2019 was quoted saying the joint exercise “targets building mutual trust, enhancing cooperation between the Saudi Royal Navy and the Chinese PLA Navy, exchanging experiences, developing the capacity of participants to combat maritime terrorism and piracy, and improving training and combat readiness” (Arab News, November 17, 2019).