The Ural Summits: BRIC and SCO

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 6 Issue: 119

By:

On June 15-16 Russia managed to hold two major heads-of-state summit meetings in the city of Yekaterinburg. That Yekaterinburg was chosen as the site is perhaps fitting, because it marks the geographical beginning of Russian Asia. These two summits were, for the most part, about Russia’s Asia partners. The Sino-Russian relationship, however, was clearly the fulcrum for both summits. These summits provided an ideal opportunity for the Chinese and Russian leaders to advertise their close partnership, and to give the occasional gratuitous poke at Washington. Nevertheless, the inability to articulate a clear vision for either of the summit organizations, confirms that apart from disenchantment with Washington, there is little else that strategically binds the two nations.

The Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) convened its annual two-day summit on June 15. The SCO normally covers regional security issues, and this year was no different. But the leaders of the SCO nations – like last year in Dushanbe – faced challenges over reaching consensus on certain fundamental issues, such as the question of Iranian membership (Iran is an observer nation), and the type of support available for the NATO mission in Afghanistan.

Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, fresh from his controversial re-election, arrived on the second day of the SCO summit. Tajikistan has supported Iranian membership, but both Russia and China are opposed. One Russian expert said, "If the decision [to accept Iran] is made, it will indicate a wholly new vector of a confrontation between Russia [and the West]" (Nezavisimaya Gazeta, June 16). Likewise, Pakistan – also an observer – has been pushing for full membership, but Russia and the Central Asian members oppose this, keeping in mind the observer status of India (Moscow Times, June 16).

Afghanistan poses another challenge for the SCO, especially for the security of Central Asia. In March, Moscow began allowing the transit of non-military goods across Russia to U.S. and NATO partners in Afghanistan. But earlier this year, Kyrgyzstan -most likely with Russian collusion- announced that it was forcing the United States from a vital logistical airbase at Manas. At the Yekaterinburg summit, Afghan President Hamid Karzai met with Kyrgyz President Kurmanbek Bakiyev to ask him to reconsider the closure of the base. The Kyrgyz government has remained firm in its intentions, although the indications are that talks are still underway between U.S. and Kyrgyz officials (Nezavisimaya Gazeta, June 15). Furthermore, Uzbek President Islam Karimov outlined a proposal for a new U.N. peacekeeping mission in Afghanistan that would entail consultation among the primary stakeholders in the region: NATO, Russia, and the six nations bordering Afghanistan (China, Iran, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan) (RIA Novosti, June 16).

Meanwhile, for Russia the threat of the SCO becoming a Chinese Trojan horse is ever-present. On the sidelines of the summit Chinese President Hu Jintao met with the leaders of Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. The Chinese government has pledged up to $10 billion in loans to the five nations of Central Asia that are struggling through the economic crisis (The Times, June 17). Apart from a $2 billion loan to Kyrgyzstan (which some suggest is a bribe to expel the U.S. base from Manas), Russia has been AWOL to many of the states in the region that are looking for leadership amidst the crisis.

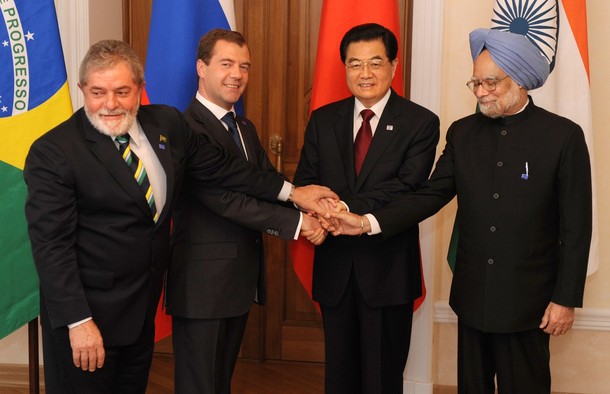

At the conclusion of the SCO summit on the evening of June 16 the four leaders of the BRIC group of nations (Brazil, Russia, India, and China) met to discuss global economic issues. Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva of Brazil, Hu, and Medevedev took turns criticizing the United States and Western financial institutions for their failed leadership during the economic crisis. The BRIC nations account for close to half the world’s population, but just one-fifth of the global economy. BRIC leaders made calls for a revision of voting rights in the IMF and a review of special drawing rights (SDR), but recent demands for the replacement of the dollar as a the premier reserve currency were somewhat tempered (Moscow Times, June 15-16).

The BRIC nations hold a combined $2.8 trillion in their reserves. At the summit Medvedev said, "The existing set of reserve currencies including the U.S. dollar, have failed to perform their functions" (Reuters, June 16). But Finance Minister Alexei Kudrin gave assurances over the preceding weekend that Russia will not reduce the proportion of U.S. government debt in Russian reserves (RBC, June 17). China is particularly wary about criticizing the dollar, as it has the largest amount of dollar-denominated debt in its reserves, and a fall in the value of the dollar negatively affects these holdings. Like the SCO, the BRIC summit, appears to be more of a photo opportunity than a venue to truly discuss and resolve pressing economic matters. The director of the Center for Russia and Eurasia at the Rand Corporation Andrew S. Weiss, commented that, "the dirty secret in Yekaterinburg is that the BRIC countries have little in the way of a common policy agenda" (Foreign Policy, June 15).

Clearly, China and Russia see eye-to-eye on any number of issues. In the first quarter of 2009 China supplanted Germany as Russia’s top trading partner. But as one Russian report suggested, they are "partners, not allies" (RIA-Novosti, June 17). Russia’s latent fear of the Chinese economic and demographic threat to the Russian Far East was reawakened earlier this year when the state-owned oil firm CNPC extended a loan of $25 billion to two Russian energy companies in return for deliveries of Siberian oil over a twenty-year period.

In a speech earlier this month Medvedev touted the SCO summit as an opportunity to "build an increasingly multi-polar world order," which might supplant the "artificially maintained uni-polar system" (Financial Times, June 15). As much as the leadership of Russia might desire the establishment of a multi-polar system, the trends seem to indicate otherwise. China’s growing economic, military, and political strength, combined with the still-preponderant power of the United States suggests that in the not-too-distant future another bipolar system might arise, and Russia could be left on the margins.