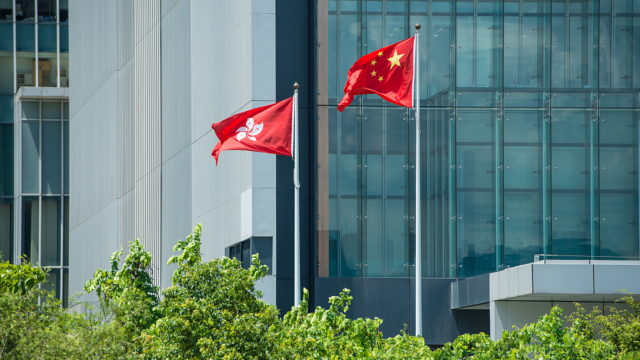

The US-China Hong Kong Sanctions Face Off

Publication: China Brief Volume: 21 Issue: 20

By:

Introduction

Since the passage of the Hong Kong National Security Law (NSL) on July 1, 2020, the US has sanctioned 42 individuals for their role in the imposition of the law. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) has responded with countersanctions targeting the US, and an Anti-Sanctions Law in the Mainland with similar legislation under discussion in Hong Kong. These tit-for-tat US-China sanctions are indicative of how Hong Kong, once a source of connectivity between the US and China, has become a growing source of contention in an increasingly fraught relationship.

Legislation and Impact

The PRC’s National People’s Congress Standing Committee directly adopted an NSL for Hong Kong based on its powers under Article 18 of the Basic Law, Hong Kong’s de facto mini-constitution that implements the Sino-British Joint Declaration, thereby circumventing any input or consultation with the Hong Kong government. (General Office of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress, June 30, 2020), thereby circumventing any input or consultation with the Hong Kong government. Although many local people (including Hong Kong politicians) opposed the NSL, they did not have the political space or tools to effectively do so.

The NSL establishes the crimes of secession, subversion, terrorist activities, and collusion with a foreign country or with external elements endanger national security. These offenses can occur if a person simply “organizes, plans, commits or participates in any of the following acts [related to secession and subversion] by force or threat of force or other unlawful means with a view to subverting the State power” and “terrorism” is strategically left undefined. Furthermore, Article 38 has raised concerns surrounding extraterritorial jurisdiction over all non-Chinese citizens, as “[t]his Law shall apply to offenses under this Law committed against the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region from outside the Region by a person who is not a permanent resident of the Region” (Hong Kong Government, June 30, 2020). If broadly interpreted, this article could criminalize any criticism of the Chinese government by anyone, anywhere in the world. Despite concerns over the NSL’s ambiguity, there has not been an official clarification or guidance on the legislation from the PRC. This had led many observers to conclude that the NSL is intended to reduce civil and political space, including critique and dissent, at home and abroad.

In the first year since the NSL’s initial passage, Beijing has successfully established new offices and committees which ensure smooth monitoring and implementation of the law. These arrangements combine mainland and Hong Kong politicians and civil servants together, increasing Beijing’s direct role in local governance, and further eroding Hong Kong’s autonomy under “One Country, Two Systems.” The High Court’s first NSL verdict found that Tong Ying-kit (唐英杰) was guilty of inciting secession and terrorist activities. Tong was given a nine-year jail sentence, for driving a motorcycle with a flag reading “Liberate Hong Kong, revolution of our times” into three police officers during a 2020 demonstration (Hong Kong Free Press, July 30). Tong’s imprisonment show that the Hong Kong judiciary is keen on strictly implementing Beijing’s NSL too. Other NSL cases, such as Jimmy Lai’s ongoing trial on national security charges, where the maximum penalty is life imprisonment (Hong Kong Free Press, June 15), reveal that many of the worst fears surrounding the NSL are becoming a reality. For example, after Lai was arrested, the International Press Institute condemned the move stating it “further confirms what we already knew: the PRC’s so-called ‘national security’ law was imposed as a tool to abolish fundamental freedoms in Hong Kong, chief among them press freedom” (IPI, June 17).

Sanctioned Individuals

From August 7, 2020, until July 16, 2021, the US Department of the Treasury sanctioned 42 individuals for their roles in the imposition of the NSL invoking the Hong Kong Autonomy Act of 2020, Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act of 2019, the Global Magnitsky act and a series of executive orders on Hong Kong

(US Department of the Treasury, August 7, 2020; US Consulate General Hong Kong & Macau, November 9, 2020; US Department of the Treasury, December 7, 2020; US Consulate General Hong Kong & Macau, January 15; U.S. Department of the Treasury, July 16). Among these, all 14 Vice Chairpersons of the National People’s Congress (NPC) of the PRC were sanctioned, while the rest were Hong Kong-based politicians and civil servants. The PRC responded that this was an “outrageous, unscrupulous, crazy and vile act” which will “trigger greater indignation” (Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the Kingdom of the Netherlands, 8 December, 2020).

The US has now sanctioned nearly all the officials directly linked to the NSL but has refrained from acting against the most senior level officials who oversee the PRC’s policy toward Hong Kong. For example, while others in the NPC leadership were subject to sanctions, NPC Standing Committee Chairman and Politburo Standing Committee Member Li Zhanshu, was not sanctioned (Bloomberg, December 10). Vice Premier and Politburo Standing Committiee Member Han Zheng who leads the Central Leading Group on Hong Kong and Macau Affairs (中央港澳工作协调小组, zhongyang gangao gongzuo xietiao xiaozu) has also evaded US sanctions, as has General Secretary Xi Jinping. The US then also issued a business advisory, emphasizing that the legal landscape, specifically that the NSL, “could adversely affect businesses and individuals operating in Hong Kong. As a result of these changes, they should be aware of potential reputational, regulatory, financial, and, in certain instances, legal risks associated with their Hong Kong operations.” (US Department of the Treasury, July 16).

Countersanctions and Anti-Sanction Laws

In response to the US sanctions, the PRC imposed sanctions on 46 American nationals (FMPRC, August 10, 2020; FMPRC, January 21; FMPRC, July 23). The PRC argues that doing so is a way of treating the US in a way that is equal, and hence reciprocal, to what it has been subjected to. However, the sanctioned people are not directly involved in the U.S. sanctions on the PRC nor are they critics of the NSL. Rather, the sanctions appear to be an opportunity for PRC retribution against to individuals that it dislikes. The PRC blamed “anti-China politicians” and “selfish political interests and prejudice and hatred against China” as the reasons for US sanctions (FMPRC, January 20) and claimed that the US “severely violates basic norms governing international relations” and interferes in the PRC’s internal affairs (Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in Finland, August 8, 2020). However, the PRC has never directly responded to the critiques of the NSL or its human rights violations in Hong Kong.

Additionally, on June 10, the Standing Committee of the NPC passed an Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law (The National Congress of the People’s Republic of China, June 10) which was domestically framed as a necessary countermeasure against unfair sanctions on the PRC (Xinhua, June 11). The law provides for three categories of countermeasures, which are related to visas, entry into the PRC, and deportation; sealing, seizing, and freezing property and assets; and prohibiting sanctioned individuals from conducting transactions with domestic organizations or individuals (The National Congress of the People’s Republic of China, June 10). The passage of the Anti-Sanctions Law also furthers the PRC’s narrative that Western countries are unfairly and unjustifiably smearing their policies, which explains this reaction. However, the impact is small due to the number and type of people affected.

Beijing also drafted an Anti-Sanctions Law for Hong Kong, but the vote on the legislation was postponed (South China Morning Post, 20 August). As Hong Kong is already the subject of a US business advisory, the Anti-Sanctions Law could further squeeze the business sector by precluding Hong Kong businesses from doing business with American businesses and financial institutions.

Conclusions

The NSL violates the PRC’s obligations under the Sino-British Joint Declaration, the basic law, and international human rights law, specifically the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, September 1, 2020). Nevertheless, the international community has few tools available to compel the PRC to desist from its roll back on civil and political rights in Hong Kong, and although sanctions on individuals may sting, cannot fundamentally alter the situation in Hong Kong

However, the PRC’s response threatens to further attenuate US-China economic ties in an already increasingly strained relationship. Its targets are seemingly random, and the PRC has not provided convincing justifications for its choices. In a landscape with many other politically motivated restrictions and regulations that are already impacting U.S. businesses, the countersanctions and Anti-Sanctions Law may further constrain transactions between US businesses and their Chinese and Hong Kong counterparts.

Anouk Wear is a researcher and translator focused on human rights in the China region. She obtained her BA in Social Anthropology from the University of Cambridge and her Advanced LLM in Public International Law with a specialization in Peace, Justice, and Development from Leiden University.

Notes

[1] Constitution of the People’s Republic of China, Article 66.