Tiangong-1 Launch Makes China’s Space Station Plans a Reality

Publication: China Brief Volume: 11 Issue: 19

By:

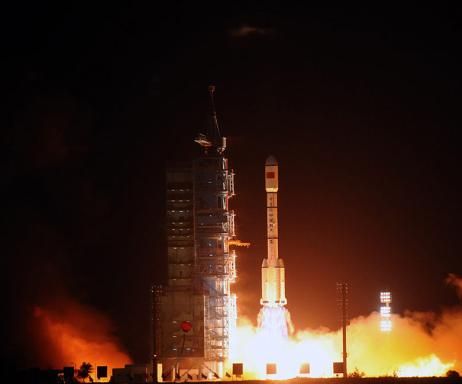

China’s successful launch of a space station on September 29 marks an important new phase in China’s human spaceflight program as it takes steps to establish a long-term manned presence in space. Tiangong-1—which means Heavenly Palace in Chinese—is China’s first space station that is intended to serve as a test bed for the eventual orbiting of a much larger space station. Tiangong-1 will be used to conduct docking experiments and to accumulate experience in the operation of space stations. Beyond scientific and technical value, the Tiangong-1 mission, if successful, also will demonstrate China’s ability to reach its goal of becoming a first-rate space power.

Basics of the Tiangong Program

Tiangong-1 is described as a simplified space station with a service life of two years. It weighs 8.5 metric tons, is 10.4 meters long, has a maximum diameter of 3.35 meters and can house up to three astronauts (China Manned Space Engineering Office (CMSE), Press Release, September 2011). By way of comparison, the International Space Station (ISS) weighs 450 metric tons, is 51 meters long, can support a crew of six and will continue in operation until 2020 when it will have been in service for 21 years. Even Skylab, the United States’ first space station launched in 1973, weighed 77 metric tons and was 26.3 meters in length, but like Tiangong-1, housed three astronauts and only operated for two years. Nevertheless, Chinese sources describe developing Tiangong-1 as a challenging endeavor, which took six years and involved overcoming 234 critical technology challenges (PLA Daily, September 30).

The launch of Tiangong-1 from the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center will be followed by the launch of the unmanned Shenzhou-8 space capsule in November to conduct docking experiments. Within two days after launch, Shenzhou-8 will dock with Tiangong-1 and will stay docked for approximately 12 days after which they will separate and dock again. After this second docking, Shenzhou-8 will separate from Tiangong-1 and return to earth (PLA Daily, September 30). Two more follow-on docking missions are planned for 2012. Shenzhou-9 will dock with Tiangong-1 and, depending on the results of the Shenzhou-8 docking experiments, may be manned. The manned Shenzhou-10 mission will follow. Each manned mission will carry two or three astronauts to the space station for short periods of habitation. During these missions, astronauts will conduct space science and medical experiments and learn how to live in space for extended periods of time.

The primary mission of Tiangong-1 is to practice using the technologies and techniques for rendezvous and docking. To align with Tiangong-1 properly, Shenzhou-8 will have to conduct five orbital adjustments. When it is within 52 kilometers of Tiangong-1, ground controllers using microwave radar, laser radar and optical imagers on Shenzhou-8 will guide it into position. During this approach, the spacecraft cannot exceed 0.2 meters per second and cannot veer more than 18 centimeters laterally from Tiangong-1. To conduct docking procedures, ground controllers will use two data relay satellites, domestic ground systems and two international ground systems in France and Brazil to control the space station (PLA Daily, September 30).

The Contours of the China’s Space Station Program

The launch of Tiangong-1 brings China closer to the ultimate goal of China’s human spaceflight program, which is to establish a long-term human presence in space with the launch of a 60-metric ton space station. The genesis of this program lies in the strategic situation of the 1980s. During the mid-1980s the Soviet Union had launched the Mir space station while the United States was planning for the development of Space Station Freedom, the precursor to the International Space Station. At that time, Chinese scientists believed major powers had space stations and to be a major power a country must have a space station. They justified such a large and expensive endeavor on the political, economic, scientific and military benefits it would provide. After a tortuous six-year process of feasibility analysis, the program was finally approved on September 21, 1992 and dubbed the 921 Project after the month and the day of its establishment. In its approval, China’s top leadership mandated a “three step” strategy for China’s human spaceflight program.

Tiangong-1 represents the second step of this strategy. The first step began with the launch of unmanned space capsules and ended with the completion of the second manned mission, Shenzhou 6, in 2005. The second step is composed of two phases. The first phase, completed with the Shenzhou 7 mission, involved a multi-day mission with multiple astronauts and a space walk. The second, current phase involves the testing and operation of small space stations. The third step involves the launch of a larger space station designed for long-term habitation ("Human Space Flight Development Strategy," Cmse.gov.cn).

In keeping with this three-step strategy, Tiangong-1 will be followed by two more small space stations. Tiangong-2 will be launched in 2013 and will be able to support a crew of three for 20 days. It will concentrate on earth remote sensing, space and earth system science, new space application technologies, space technologies and space medicine. Tiangong-3 will be launched in 2015 and will be able to support three astronauts for 40 days. The Tiangong-3 mission will focus on regenerative life support, living in space, the transportation of supplies to the space station and limited space science and space medicine experiments. The three Tiangong space stations will pave the way for a much larger 60-metric ton space station with a planned service life of 10 years that will be launched in the 2020 timeframe (PLA Daily, September 30; People’s Daily, September 27, 2001).

China has developed or is developing a number of systems to support a long-term manned presence in space. . For example, Tiangong-1 was launched on the Long March-2FT1, a variant of the Long March-2F used to launch Shenzhou space capsules. . The Long March-2FT1 has more than 170 modifications and is described as nearly a completely new rocket (China Space News, September 28). These modifications include a larger payload faring and reshaped boosters to allow for greater fuel capacity (“Mission Introduction by Tiangong/Shenzhou VIII Rendezvous and Docking Mission Headquarters,” Cmse.gov.cn, September 28, 2011). China also is developing the Long March-5, a heavy lift rocket that will be able to launch a 25-ton payload into low earth orbit. This rocket is designed, in part, to transport the long-term, 60-metric ton space station into orbit. Due to the difference in the maximum payload capacity of the Long March-5 and the mass of the space station, the space station will be constructed in pieces, with a core module being launched first, followed by separate launches for two laboratory units (Nanjing Morning News, September 30). In addition, China is developing a cargo vessel to resupply their space station (PLA Daily, September 30).

Leadership Attendance Highlights Significance to China’s Image

Although Tiangong-1 is described as a simplified space station, nearly all of China’s top civilian and military leaders observed the launch of Tiangong-1 . The presence of the top leadership not only demonstrates top level support for China’s human spaceflight program, but also for China’s space program overall. Their presence also directly links the Chinese Communist Party with China’s rise as a modern, high technology state and serves to buttress the Party’s reputation after high profile accidents, such as the crash of a high speed rail train, called into question the soundness of massive government projects. While Premier Wen Jiabao and Central Commission for Discipline Inspection Secretary He Guoqiang were on hand at the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center in Gansu Province; President Hu Jintao and the other four Politburo Standing Committee members witnessed the launch from the Beijing Aerospace Control Center. In addition, all military members of the Central Military Commission with the exception of Air Force commander Xu Qiliang witnessed the launch at the Jiuquan launch site or in Beijing (PLA Daily, September 30). The reason for Xu’s absence is unknown and is peculiar considering that China’s astronauts are Air Force pilots and the Air Force has expressed interest in taking over the space program [1]. Xu’s controversial remarks in a November 2009 interview that were widely interpreted as advocating for space warfare, raises the possibility that the Chinese leadership feared that his presence could put the launch in an unfavorable light (PLA Daily, November 1, 2009).

The presence of nearly all of China’s top military leadership to witness the launch is a reminder that China’s space program, including its human spaceflight program, is managed by the military through the General Armament Department (GAD). Indeed, GAD head General Chang Wanquan is the commander of China’s human spaceflight program. The Chinese Ministry of National Defense defends the military’s involvement in China’s human spaceflight program as both a necessity brought about by the size and complexity of the space program and as a common trait of all countries with space programs (Xinhua, September 30). The program’s military leadership, however, raises questions about whether China’s space stations will have military utility. For example, the technology and techniques used to rendezvous and dock with Tiangong-1 could be applied to the use of co-orbital satellites in a counter-space role. Chinese writings refer to parasitic satellites that can attach themselves to an adversary’s satellites during peacetime and then are activated to interfere with, damage or destroy the host satellites during wartime. Other satellites conducting legitimate peacetime activities can be deployed during wartime to attack an adversary’s satellite through self-detonation or through the use of kinetic, directed energy or chemical spray weapons [2].

An optical sensor on Tiangong-1 and the plan to equip Tiangong-2 with remote sensing technology also raises the possibility that Chinese space stations will conduct intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) missions (Xinhua, September 29, 2001). Indeed, Chinese writings on space warfare discuss the use of manned spacecraft, including space stations, and some describe manned platforms as more responsive than unmanned platforms [3]. Chinese researchers also state space stations could serve as a command and control base, a communications node, a surveillance and reconnaissance platform, a logistics and maintenance hub and a platform for weapon systems that can be used against space and terrestrial targets [4].

Opportunity or Challenge?

China’s space station plan presents both opportunities and challenges for the United States. For example, the launch of Tiangong-1 could present increased opportunities for international cooperation. Although Chinese space officials told NASA Administrator Charles Bolden during a 2010 visit to China “We don’t need the United States and you don’t need us,” China is open to both technical cooperation and cooperation in spaceflight (Space News, November 19, 2010). France and Brazil have allowed China to use their telemetry, tracking, and control (TT&C) facilities for the Tiangong mission and China is also cooperating with Russia on joint exploration of Mars. Moreover, an article in China Space News assessed China’s success in developing space station technologies will make it a more attractive partner for participation in the ISS (China Space News, September 30). Yang Liwei, China’s first astronaut and deputy director of the China Manned Space Engineering Office, also voiced support in April for cooperation with the United States (Reuters, April 29). In addition, Zhou Jianping, the Chief Designer for China’s human spaceflight program, stated in an interview “We [China] are willing to engage in international cooperation with any country, on the principles of mutual respect, equality, and mutual benefit, on human spaceflight in order to propel world human spaceflight to a higher level” (PLA Daily, September 30).

China’s space station missions, if successful, also may further fuel the perception of China as a rising power and the United States as a super power in decline. In this respect, Tiangong-1 is an important symbol of China’s technological power and a reminder that as the United States has terminated its Space Shuttle program with no immediate replacement, China remains committed to becoming a first rate space power. China’s space stations, even the 60-metric ton space station to be launched around 2020, will still be less advanced than the ISS. China disagrees with such analysis, stating China’s space station is built solely by China and not an international partnership like the ISS and, even though the ISS may be larger, the technologies on the Tiangong-1 are just as advanced (China Space News, September 30). Nevertheless, NASA’s plan to build the Space Launch System and the Orion Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle could mean the United States will have the capability to send humans into deep space, including Mars, while China is still stuck in low Earth orbit. Reaching these destinations however will require vision and political will on the part of the United States. Qualities China has not been shy about demonstrating. Indeed, although no official decision has been made for a manned lunar program, China now is conducting preliminary feasibility studies to send humans to the moon [5].

Notes:

- See, for example, “China Should Build a Mighty Air Force," China Military Online, August 29, 2009; Cai Fengzheng and Deng Fan, "Kongtian zhanchang yu guojia kongtian anquan tixi chutan [Introduction to the Air and Space Battlefield and National Air and Space Security System],” Zhongguo junshi kexue [China Military Science], 2006/2, p. 50.

- Jiang Zhibao, Zheng Bo, and Hu Wenhua, “Xin gainian wuqi de yanjiu xianzhuang yu fazhan qushi [Current State and Trends in Development of New Concept Weapons],” Feihang daodan [Winged Missiles Journal], Issue 11, 2005, pp. 16, 25.

- Li Yiyong, Li Zhi and Shen Huairong, “Linjin kongjian feixingqi fazhan yu yingyong fenxi [Analysis on Development and Application of Near Space Vehicle],” Zhuangbei zhihui jishu xueyuan xuebao [Journal of the Academy of Equipment Command and Technology], 2008/2, p. 64 and ; Chang Xianqi, Junshi hangtianxue [Military Astronautics], Beijing: National Defense Industry Press, 2002, pp. 118-119.

- Cai Fengzhen and Tian Anping, Kongtian zhanyang yu zhongguo kongjun [The Air-Space Battlefield and China’s Air Force], Beijing: Liberation Army Press, 2004, pp. 123 and 131.

- Presentation by China Manned Space Engineering Office representative Zhang Haiyan at the International Astronautical Federation’s 62nd International Aeronautical Conference on 6 October 2001 accessed at https://www.iafastro.org/index.html?title=IAC2011_Late_Breaking_News_2