Türkiye’s Heterodox Economic Policy Requires More Foreign Financing

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 19 Issue: 128

By:

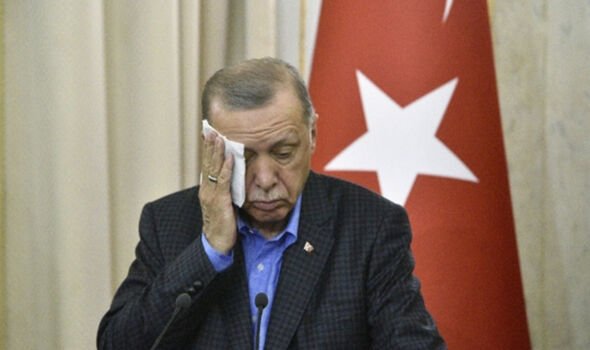

In less than a year, parliamentary and presidential elections will be held in Türkiye. Nevertheless, this time the odds will be quite different for the ruling Justice and Development Party. Current economic indicators do not favor Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s government due to skyrocketing inflation and the dramatic depreciation of the Turkish lira. The inflation rate was at 79.6 percent in July 2022, and the Turkish lira has been in free fall since November 2021. Naturally, polls show that the top issue on the agenda for Turkish electorates is the current economic situation (Hürriyet, July 22).

One main reason for the current negative outlook in the Turkish economy is the deteriorating global economic balances in the post-pandemic period. Coupled with regional crises, such as the war in Ukraine, commodity prices have hiked up and increased the burden on national economies. Beyond these factors, double-digit inflation in Western economies resulted in a shift to orthodox monetary policies by most central banks. In this respect, the US Federal Reserve’s decision to increase the interest rate consecutively for four rounds since March 2022, from 0.25 percent to 2.5 percent, strengthened the US dollar against other currencies.

The repercussions of these developments have weighed heavily on the Turkish economy. Ankara decided to promote growth rates and exports in the economy under the label, “new Turkish economic model” in the post-COVID-19 era. The main objective of this model was introduced as solving the chronic account deficit problem in the Turkish economy while promoting production and employment. The cost of this model would be merely the depreciation of the Turkish Lira. In parallel, the Central Bank of the Republic of Türkiye (CBRT) gradually decreased the policy rate (one-week repo auction rate) from 19 percent in August 2021 to 14 percent in December 2021 with the expectation of decreasing the cost of borrowing. Subsequently, Türkiye faced a currency shock. Depreciation of the Turkish lira was so rapid that power parity plunged from 9 lira per US dollar to 18 lira in two months.

Reactively, the Erdogan government adopted a heterodox approach and developed alternative instruments to prevent further depreciation of the lira (Valdai Club, March 3). Despite the CBRT’s intervention, the parity rebounded back to 18 lira per dollar in August 2022. Moreover, the inflation rate has swelled to 80 percent, as the current account deficit problem lingers and increased to $32 billion in the first half of this year.

Yet, despite negative indicators in the monetary sphere, the Turkish economy has been growing for seven quarters since the second half of 2020. Looking at the performances of Turkish companies, they outperformed in the second quarter of 2022 by taking advantage of the current economic environment (Türkiye, August 17). It seems that the current model does promote economic growth. Yet, without structural reforms, the growth hardly converts to welfare or economic transformation in emerging sectors. Overall, the terms of trade have been decreasing despite the new economic program’s expectations. In other words, Turkish exports are growing in nominal terms, but their share in foreign trade continues to decrease.

Seeking protection from the high inflationary environment, Turkish households opt for keeping their savings in foreign currencies. This increases demand for US dollars and euros at the expense of domestic currency—known as “dollarization.” Despite new instruments introduced by the government, such as foreign exchange–protected lira deposits, it is hard to talk about a permanent reverse trend in dollarization. After peaking in December 2021, foreign exchange deposits decreased from $232 billion to $213 billion in February 2022. However, this trend reversed after April and once again reached $218 billion in August 2022.

Coupled with the growing account deficit issue, dollarization causes continuous depreciation of the Turkish lira. The CBRT uses its reserves actively to try and prevent further depreciation. On November 9, 2021, gross reserves were equal to $128 billion but depleted by $19 billion in two months. The downward trend shows that the CBRT continues to use its reserves to defend the lira against further depreciation even after the currency shock in December 2021.

Nevertheless, the downward trend relatively reversed after plunging to $98 billion in July 2022. The reserves rapidly recovered in two weeks and reached $113 billion on August 12. Economists, such as Uğur Gürses, claim that this increase is mainly linked to incoming Russian funds to Türkiye as part of the Akkuyu Nuclear Power Plant project (T24, August 8). Recently, it was also reported that Akkuyu’s main shareholder, Rosatom, has raised funds estimated at $6.1 billion and pledged “Turkish dollar bonds to secure the credit line” (Middle East Eye, July 30).

In fact, Ankara is expecting an additional $55 billion in funds from Saudi Arabia, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates and Russia (Yetkin Report, August 15). The estimated value of Russian funds, linked with the Akkuyu project, is between $2.1 billion and $7.5 billion. Indeed, somehow Türkiye has received a decent amount of financing in August to supplement the Akkuyu funds. The $15 billion increase in the reserves, since the end of July 2022, indicates that Türkiye managed to attract more funds from elsewhere.

On August 18, the CBRT cut the policy rate by 100 base points to 13 percent. Such a decision reflects that the Turkish government will not compromise on its heterodox policies despite the unfavorable indicators. Nevertheless, the sustainability of this policy depends on financing the needs of the Turkish Ministry of Treasury and Finance by printing more money or borrowing from abroad.

Since the pandemic, money supply has been increasing steadily in parallel with expansionist policies. Moreover, the currency shock in December 2021 shows that the economy can easily spiral into another crash. Despite the floating exchange rate regime, the CBRT tries to prevent this scenario by actively using its reserves and easing the pressure on markets. The sustainability of this strategy is questionable, but before the upcoming elections, austerity policies will be riskier for the government’s popularity.

Thus, the above scheme requires borrowing money from abroad to fine tune instruments. Acquiring funds from conventional mechanisms is too costly considering Türkiye’s current credit default swap premiums. Rather than looking for financing from traditional sources, the Turkish government pushes political channels instead. Recently, Russia seems to have played a critical role by injecting money into the Turkish system. Pursuing a normalization policy with the Persian Gulf states, Ankara also tries to attract more funds from the region. Obviously, the risks in the commodity markets linger as the Ukrainian conflict continues. Thus, securing more funds from abroad is more critical than ever before as elections appear on the horizon for Erdogan and his government.