Ukraine as Clandestine Testing Ground for Russian Electronic Warfare

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 15 Issue: 157

By:

The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe’s (OSCE) Special Monitoring Mission (SMM) to Ukraine reported at the end of October that one of its long-range unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) had gone missing. According to an OSCE spot report (Osce.org, October 27), the drone disappeared while flying above a non-government-controlled area in Donetsk region. The UAV in question apparently experienced signal interference—which the OSCE SMM assessed to be jamming—while operating at an altitude of about 7,000 feet (2.1 kilometers).

Coincidentally or not, the UAV went missing only two days after the deputy head of the OSCE’s SMM in Ukraine, Alexander Hug, gave a telling interview to the Washington-based Foreign Policy magazine. Specifically, he stated that while the OSCE had not detected direct evidence of Russian involvement in eastern Ukraine, SMM observers had repeatedly seen various types of advanced weapons produced by Russia, including electronic warfare (EW) equipment. In fact, the SMM has already observed a number of the newest examples of Russian EW systems, such as the Leer-3 RB-341V, 1L269 Krasukha-2 and RB-109A Bylina, and an anti-UAV system—the Repellent-1 (Osce.org, August 11).

The main objectives of Russian electronic warfare in Ukraine include detecting and identifying the location and source of radio emissions; suppressing all types of mobile satellite communication (including Inmarsat and Iridium satellite systems, GSM 1900 mobile phones, and cell stations) and satellite-based navigation signals (including NAVSTAR “GPRS” navigation); intercepting and recording voice communications; gaining control over radio and TV frequencies; as well as jamming enemy UAVs. Russian EW was extremely effective during the first years of conflict in eastern Ukraine, particularly due to the widespread lack of encrypted digital communication systems used by the Ukrainian Armed Forces (see EDM, May 24, 2017; July 19, 2017; April 17, 2018).

But importantly, Russia has also used EW capabilities to conduct so called “psy-ops” and diversionary operations. In early 2014, even before Russia annexed Crimea or initiated armed separatist activities in Donbas, the website Livyi Bereh reported that some individuals in downtown Kyiv received text messages that said, “You have been registered as a participant in riots” (Livyi Bereh, January 21, 2014).

The Ukrainian State Center for Radio Frequencies (USCRF) subsequently declared in a special report that it found no evidence of penetration of Ukrainian mobile operator networks. As Pavlo Slobodyanyuk (then the head of the USCRF) told the news outlet Capital.ua, an unknown international mobile subscriber identity-catcher (IMSI-Catcher) could have been the possible source of such activity (Capital.ua, February 3, 2014). And notably, a ground-based mobile EW station was spotted in Sevastopol, Crimea, near the Ukrainian Navy’s 72nd psy-ops center, just before the annexation of the peninsula in March 2014 (Ukrainska Pravda, March 22, 2014). Some of the Ukrainian officers and commanders, speaking with this author on the condition of anonymity, revealed that their cellphone conversations had been intercepted and reported that they had received text messages with proposals that they surrender.

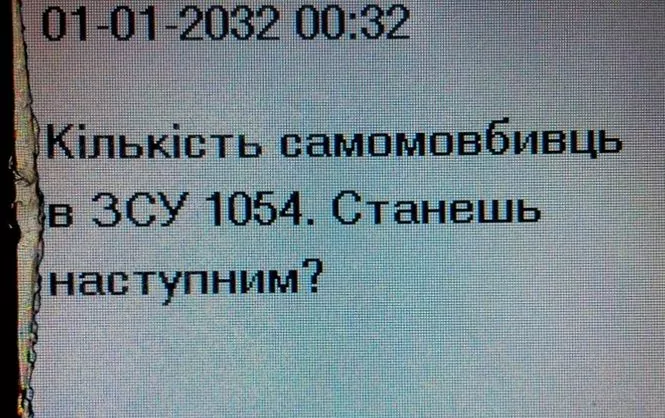

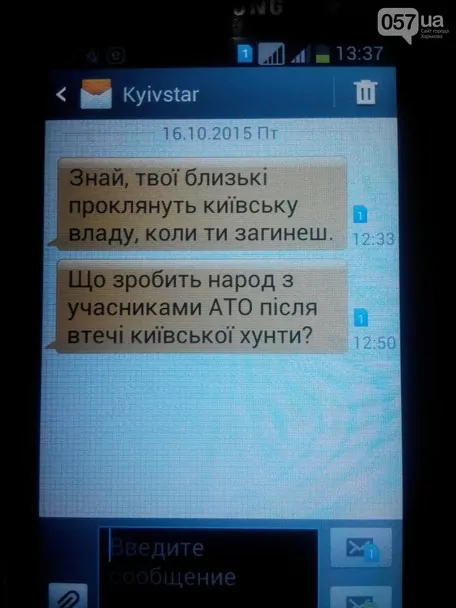

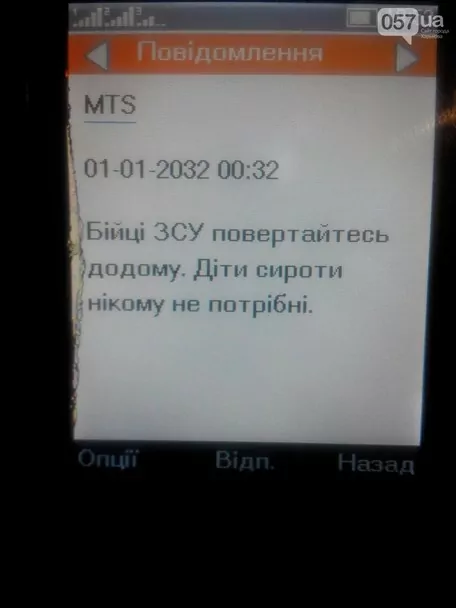

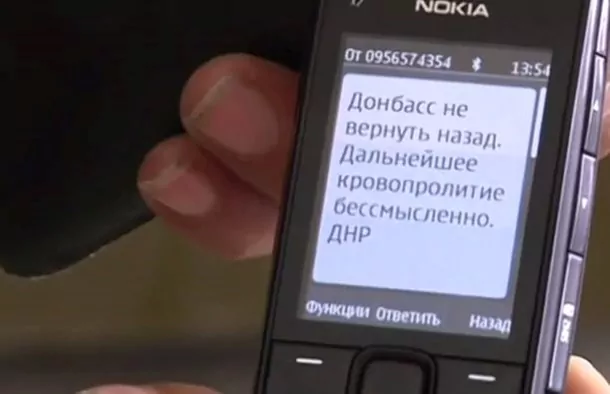

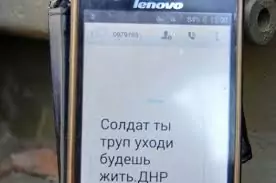

Combined Russian-separatist forces later employed similar methods on the front lines in Donbas. During the most significant battles, such as Ilovaysk (August–September 2014) or Debaltseve (February 2015), Ukrainian troops received multiple intimidating mobile phone texts designed to sow panic and mistrust (Livyi Bereh, February 6, 2015).

These messages were also found delivered to cell phones owned by civilians who were present in the combat zones at that time. Such texts continued to be sent to recipients in Donbas from time to time (UNIAN, July 22, 2015). Notably, according to Ukrainian military intelligence, soldiers from Russia’s 338th Radiotechnical Regiment (4th Air Force and Counter-Air Defense Army, North Caucasus Military District) were identified operating in Donetsk region as early as 2015 (InformNapalm, April 11, 2015).

Most recently, according to an anonymous source in the Ukrainian Navy, also interviewed by this author, Russian forces used EW systems in an attempt to suppress communication by two Ukrainian ships, the sea tow Korets and the search-and-rescue vessel Donbas, as they passed through the Kerch Strait on September 23, 2018 (Toinformistoinfluence.com, September 24; TASS, September 25). Ukraine deployed these two ships to the Sea of Azov in response to growing tensions with Russia in this shared body of water.

According to investigations carried out by the international volunteer community InformNapalm, at least 12 different Russian EW systems have been spotted and documented in eastern Ukraine (InformNapalm, accessed November 2). All of these systems are Russian-made and none have ever been purchased by the Ukrainian government or officially transferred to Ukraine. Most have been developed only in the last decade—for example, the R330Zh was introduced in 2008, and the Krasukha-2 in 2012. A number of these models were also deployed to Syria last September (Interfax, September 24), following the deadly incident when a Russian Il-20 military surveillance plane was mistakenly shot down by Syrian air-defense units. The Russian Ministry of Defense blamed the Israeli Air Force for the downing of the Russian plane because Israeli aerial operations had drawn the Syrians into trying to engage. In response, Russia sent additional anti-air as well as EW systems into the Syrian theater in order to strengthen its Anti Access/Area Denial (A2/AD) capabilities protecting Russian troops from hostile forces (see EDM, September 27). According to Russian media, these new EW systems in Syria may include the Krasukha-4, R330Zh and even the newest EW complex Divnomorye (Izvestia, September 25).

Russia has for years used Ukraine as a testing ground for its military industry and new military tactics and capabilities. This is also pointedly true in the case of electronic warfare. And the two major operations it is conducting—in Donbas and Syria—clearly help buttress one another when it comes to EW tactics and strategy. Russia’s wars in Syria and Ukraine should thus not be looked at in isolation.