Ukrainian Minerals Deal Must Balance Energy Independence with International Commitments

Ukrainian Minerals Deal Must Balance Energy Independence with International Commitments

Executive Summary:

- Ukraine holds Europe’s largest reserves of uranium and aims to become self-sufficient in domestic uranium production by 2027.

- Ukraine and the United States are debating how a critical minerals deal could factor into potential security guarantees or a peace settlement in Russia’s war against Ukraine.

- Any critical minerals deals involving uranium will require Ukraine to balance its domestic nuclear fuel needs with commitments to export uranium abroad.

On February 28, Ukraine and the United States were poised to sign a landmark deal on critical minerals in Ukraine. The “Bilateral Agreement Establishing Terms and Conditions for a Reconstruction Investment Fund” would have created a fund jointly held by the United States and Ukraine, with 50 percent of the financing coming from the “future monetization” of Ukraine’s natural resources (See EDM; Kyiv Independent, February 26). Uranium has been one of the key minerals under discussion, and thereby represents a potential mechanism by which Kyiv may be able to achieve its goals in reaching a lasting peace agreement with security guarantees. If such an agreement is reached, Ukraine will need to balance between its own domestic nuclear fuel supply goals as well as any new uranium export commitments to partners abroad.

The signing of the deal was canceled after the public dispute between Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy and U.S. President Donald Trump in the White House. This has created uncertainty over whether or not a new deal will be signed or if alternative partners may now express interest (See EDM, March 3). Zelenskyy stated in a press conference on March 2 that Ukraine remains ready to sign the minerals deal with the United States (BBC News, March 3). On March 6, U.S. Special Envoy to the Middle East, Steve Witkoff, told reporters that Zelenskyy has offered to sign the deal (RBC-Ukraine, March 6).

Ukraine’s uranium reserves are the largest in Europe and represent 2 percent of estimated global reserves (Ukrainian Geological Survey, accessed March 6). Enriched uranium is primarily used as fuel for nuclear reactors. This involves undergoing a process to increase the isotopic proportion of U-235 from 0.72 percent to up to 20 percent (International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), September 3, 2024). Conversely, highly enriched uranium, which has an isotopic proportion beyond 20 percent, is mostly used for military and research purposes (IAEA, September 3, 2024). U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has included uranium among the strategic minerals that are of American financial interest, saying that the deal overall represents an “economic security guarantee” for Ukraine (Fox News, February 24). This is in line with the Executive Order on “Unleashing American Energy,” signed by U.S. President Donald Trump on January 20, to potentially add uranium to the U.S. Geological Survey’s list of critical minerals (The White House, January 20).

Prior to Russia’s full-scale invasion, Ukraine’s nuclear reactors produced 51 percent of the country’s electricity supply (IAEA, 2022). Nuclear energy is a major part of Ukraine’s energy mix and a mechanism for balancing against reliance on Russia for domestic energy needs (Davis, 2022).

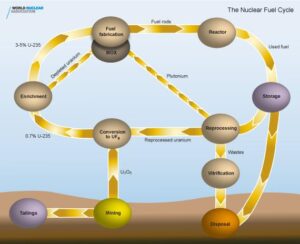

Figure 1: The Nuclear Fuel Cycle

Uranium supply is essential to ensuring Ukrainian energy independence in its nuclear sector. Kyiv aims to become self-sufficient in supplying its uranium needs by 2027 (World Nuclear News, January 5, 2022). Since 1994, Ukraine has officially sought to establish a domestic nuclear fuel cycle (see Figure 1), which includes “uranium ore mining to disposal of radioactive waste” (President of Ukraine Leonid Kravchuk, 1994). At that time, then-President Leonid Kravchuk issued a decree to pursue nuclear fuel “independence from external factors” (President of Ukraine Leonid Kravchuk, 1994). Petro Kotin, president of Ukraine’s nuclear corporation Energoatom, announced in 2023 that completion of a domestic nuclear fuel cycle could be achieved by 2026, although an exact deadline has not been set (Energoatom, Accessed April 11, 2024). The latest “Energy Strategy of Ukraine of the period until 2035” envisages Ukrainian self-sufficiency in the manufacturing of nuclear fuel, emphasizing the importance of reducing dependence on foreign suppliers, including but not limited to Russia (Rada, August 18, 2017).

The question remains as to whether Ukraine is capable of meeting its own goal of supplying 100 percent of its nuclear fuel needs in addition to being able to export uranium to its partners abroad. If the latter factor is not achievable, this complicates the inclusion of uranium in any mineral deals with the United States or other partners. The answer to this question, according to a high-ranking Ukrainian energy expert, is “potentially, yes” (Original Interview Conducted by the Author, February 28). Today, Ukraine operates a total of three uranium mines (Ingulskaya, Smolinskaya, and Novokonstantinovskoye) through the state-owned company VostGOK. Data from 2024 reveals that these mines supply 20 to 40 percent of fuel needs for Ukrainian nuclear power plants (NPPs) (Ukrainian Geological Survey, accessed March 2). In 2020, Ukraine’s 15 nuclear reactors required 2,480 metric tons of uranium (tU) (IAEA, 2022). At present, 6 of these reactors are under Russian occupation at the Zaporizhzhia NPP. If Ukraine needs 2,480 tU per year for 15 reactors (using U-235) and in 2021 Ukraine met 30 percent (744 tU) of this need with domestic uranium supply, we can therefore assume that Ukraine needs to be able to produce an additional 1,736 tU per year in order to be self-sufficient. This estimate represents an absolute minimum, as it focuses only on the final product of the time-intensive process of turning mined uranium into ready fuel assemblies, which would necessitate additional production. This might mean, for example, that Ukraine must be able to have the ability to mine and process 2,000 tU a year before it has any additional uranium to export abroad.

Fortunately, Ukraine’s recoverable uranium supplies are extensive. The relative feasibility of extracting uranium supplies is generally classified by how expensive the ore is to extract into four categories: <$40/kgU (meaning less than $40 per kilogram of uranium metal mined), <$80/kgU, <$130/kgU, and <$260/kgU. According to the latest IAEA “Red Book” on global uranium resources, production, and demand, Ukraine’s identified recoverable uranium classified as reasonably assured and inferred was 185,389 tU at costs of <$260/kgU tU and 71,841 tU at costs of <$80/kgU, as of 2021 (see Figure 2) (IAEA, 2022). Additionally, estimated undiscovered in situ uranium resources amount to 277,500 tU, including deposits on the flanks of identified deposits and those based on prognostic data (IAEA, 2022). These numbers are promising when considering both Ukraine’s domestic uranium needs and interests in exporting uranium, including via any potential mineral deals.

Figure 2: Cost Ranges of Ukrainian Uranium Reserves (in tU)

| <$40/kgU | <$80/kgU | <$130/kgU | <$260/kgU |

| 0 | 71,800 | 107,200 | 185,400 |

(Source: IAEA, 2022)

Increasing the amount of uranium mined domestically, however, is not enough to achieve self-sufficiency because the uranium must first be enriched and then assembled into fuel rods before it can be used in a reactor. Ukraine does not currently have these capabilities. At present, Russia and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) account for more than half of the global uranium enrichment capacity, while Russia alone accounts for 40 percent (International Energy Agency, January; Ukrainian Geological Survey). Prior to Russia’s full-scale invasion, Ukraine sent its uranium to Russia for fuel fabrication (the process of assembling enriched uranium into fuel rods), which would then be sent back to Ukraine’s nuclear power plants for use inside the country’s reactors. Since the full-scale invasion, Ukraine has halted procurement from Russia and instead has partnered with Westinghouse, a U.S.-based company, and Cameco, a Canadian company, for its nuclear fuel needs.

Ukraine has long cooperated with international partners to diversify its nuclear fuel needs. One of the most promising early instances of this was in August 2005, when the first trial operation of six Westinghouse fuel assemblies was started at Unit 3 of the South Ukraine NPP (Westinghouse Nuclear, July 19, 2018). In 2006, the “Energy Strategy of Ukraine for the period up to 2030” outlined the need to diversify Ukraine’s nuclear fuel sources from Russia to incorporate other foreign suppliers who could create fuel assemblies capable of fitting into Ukraine’s VVER reactors (the hexagonal design shape of VVER fuel rods is a design trademark) (Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine, 2006; Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, 2022). Additional Westinghouse fuel assemblies were loaded in 2009 after problems were resolved over manufacturing defects and errors in fuel loading (World Nuclear Association, March 25, 2024). In September 2023, non-Russian nuclear fuel was loaded into a VVER-440 reactor at Ukraine’s Rivne NPP for the first time (Energoatom, September 10, 2023). According to Halushchenko, this demonstrated that “Russia’s monopoly on this fuel type is over” (Pravda, September 10, 2023). In 2024, Ukraine and Westinghouse announced plans to construct a facility to produce nuclear fuel for VVER-1000 reactors (designed by Russia’s state-owned nuclear corporation, Rosatom) (Interfax, October 17, 2024). According to one high-ranking Ukrainian energy expert, the construction of such a facility is expected to take three years (Original Interview Conducted by the Author, February 28).

In 2023, Energoatom and Cameco signed an agreement to dispatch uranium mined at Ukraine’s Eastern Mining and Processing Plant (SkhidGZK) to Canada for conversion into natural uranium hexafluoride (UF6) (Cameco, February 8, 2023; World Nuclear News, September 18, 2023). It will then be sent for enrichment to Urenco (a U.K.–Dutch–German company), then to Westinghouse for manufacture, then back to Ukraine. The agreement is meant to supply fuel for Rivne NPP, Khmelnytskyi NPP, and South Ukraine NPP from 2024 until 2035 (Energoatom, Accessed June 11, 2024; Urenco, Accessed June 11, 2024).

Ukraine’s uranium reserves hold promising potential for achieving domestic energy independence and advancing its nuclear fuel cycle, in addition to serving as a possible mechanism for achieving security guarantees in any peace agreements. Any such deals would need to take into account Ukraine’s commitment to protecting against reliance on foreign actors for critical energy needs as well as the provision of necessary security guarantees to ensure Ukrainian territorial integrity and sovereignty.