Uzbekistan and Tajikistan Try to Mitigate Water Disputes

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 12 Issue: 105

By:

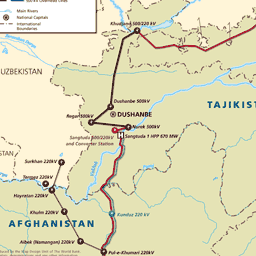

In April 2015, the parties to the CASA-1000 project (Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan and Pakistan) signed a number of important legal documents that allow them to finally break ground on the project (Casa-1000.org, April 27, accessed June 5). The construction of the large-scale electricity transmission project, which plans to facilitate the export of electricity produced via hydro-power in Central Asia to consumers in South Asia, is set to start this summer. The downstream Central Asian republics not a part of CASA-1000 (Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan) are still highly concerned by this project. However, more recent positive developments between Uzbekistan and Tajikistan now have the potential to mitigate the negative regional consequences that might arise as a result.

In January of this year, Nisha Biswal, the Assistant Secretary for South and Central Asian Affairs at the US Department of State, repeated her earlier assertions that the intention of CASA-1000 is to “bring stability and prosperity” for participating power-generating countries (State.org, January 22). The project is a part of the State Department’s New Silk Road Initiative that seeks to foster the reconstruction of Afghanistan by way of cross-border cooperation. By design, CASA-1000 does not require the construction of any new power generation capacity and does not intend to affect downstream countries. Rather, the CASA project establishes electricity transmission lines and infrastructure to sell surplus electricity to consumers in Afghanistan and Pakistan. Still, the construction of new high-capacity power transmission infrastructure is enough to cause concern among Central Asia’s downstream countries that share upstream Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan’s river resources. Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan fear that the CASA-1000 infrastructure might speed up and encourage further construction of new hydro-electric plants and hydro-dam capacities by Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. Profits that Tajikistan will receive through the project might even be used to fund the Rogun dam, whose completion has been stalled by lack of further financing.

Another reason that the downstream countries may be concerned with the project is that the electricity-buying countries, Afghanistan and Pakistan, experience chronic power shortages, which affect large numbers of their citizens. Therefore, even with the start of purchases via CASA-1000, Afghan and Pakistani leaders are may feel pressure to seek even larger imports of electricity from the upriver Central Asian producers. Pakistan, in particular, has annual shortages of around 5,000 megawatts (MW), or up to a third of the country’s total demand. Therefore, if upstream Central Asian countries are able to provide more electricity, beyond the 1,300 MW per year promised under CASA-1000, Pakistan and Afghanistan would likely not hesitate to become buyers. Indeed, Pakistan and Tajikistan, are currently studying the prospects of supplying an additional 1,000 MW—apart from CASA-1000—to the northern Pakistani district of Chitral (AsiaPlus, April 27).

Furthermore, talks on tripartite water and energy projects had been taking place among Tajikistan, Afghanistan and Iran for some time. The three sides are considering constructing a new 500-kilovolt Tajikistan-Afghanistan-Iran high-voltage power transmission line. Moreover, the partners plan to construct several medium-sized hydro power plants in Tajikistan with the use of Iranian investment funds and are discussing the possibility of exporting water from Tajikistan to Iran. The heads of Tajikistan and Iran’s electricity companies recently announced their readiness to sign an agreement on this matter (Avesta.tj, May 13).

The fact that Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan struggle to supply electricity internally during certain periods of time and face constant energy crises themselves raise questions as to how they will meet their various commercial commitments to export electricity to neighboring countries without building additional generation capacity. Moreover, the dissatisfaction of the downstream countries regarding the current state of Central Asia’s water issues is exacerbated by Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan’s failure to sign the two main United Nations conventions that regulate cross-boundary water resources: The Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes (1992) and the Convention on the Law of the Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses (1997). Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan are parties to the 1992 convention, and Uzbekistan is a party to the 1997 UN document. In particular, of all the Central Asian downstream countries, Uzbekistan has most consistently stated that the region’s water issues should be resolved through UN mechanisms.

Yet, amidst these developments, one can observe some positive steps being taken by Uzbekistan and Tajikistan following the meeting of their heads of state at the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) summit in September 2014 (Press-service.uz September 13, 2014). Dushanbe and Tashkent’s developing rapprochement promises to find common ground to resolve regional cross-border water issues, despite the CASA-1000 and other electricity trade projects that Tajikistan is planning. Uzbekistan and Tajikistan have divided all of their existing bilateral issues into three types: immediate issues that require little efforts (transportation and visa issues are among them), middle-term issues, and long-term issues, the resolution of which will require much effort. Their conflicts over water use likely fall into the latter category.

Tajikistan and Uzbekistan have already started working on the immediate issues: in particular, the heads of their respective border control agencies met in late April 2015, the first meeting of its kind since these countries’ independence (Radio Ozodi, April 27). Additionally, the two neighbors set up the Cooperation and Friendship Group between their parliaments. Notably, Tajikistan is the only Central Asian republic that Uzbekistan has such a cooperation agreement with, along with several European and Asian countries (Anhor.uz, April 27). In the midst of these developments, there is now growing potential that President Karimov’s warning of a coming regional war over Central Asian water supplies will likely be avoided.