Uzbekistan Balances Nuclear Energy Cooperation with Russia and PRC

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 22 Issue: 134

By:

Executive Summary:

- Uzbekistan is pursuing nuclear power cooperation with both Russia and the People’s Republic of China (PRC), aiming to become a nuclear energy hub in Central Asia.

- Tashkent is hedging against risks in working with Moscow due to Russia’s weakened economic position amid international sanctions placed on the country over its full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

- Cooperation with the PRC as an alternative to Russia holds risks, as access to resources could hinge on the status of Tashkent’s relationship with Beijing. Such dependencies could pose security and sustainability risks to nuclear power projects.

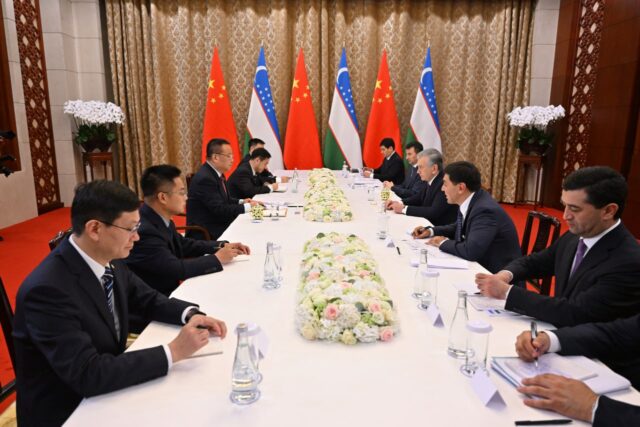

On September 2, Uzbek President Shavkat Mirziyoyev met with Shen Yanfeng, the chairman of China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC), on the sidelines of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization summit held in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Mirziyoyev and Shen explored expanding cooperation in the nuclear energy sector. The Uzbek president’s office said, “Particular attention was paid to the Chinese company’s participation in the transfer of modern technologies and the development of uranium deposits, geological exploration in promising areas, and the expansion of cooperation in the peaceful use of nuclear energy” (President of Uzbekistan, September 2).

Uzbekistan aims to become a nuclear power hub in Central Asia as it pursues an ambitious nuclear energy strategy in collaboration with Russia and the PRC (Kun.uz, April 23). According to an announcement made during the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum in June, Rosatom, Russia’s state-owned nuclear energy company, will construct four nuclear power reactors in Uzbekistan (Interfax, June 12; Telegram/@uzatom_info, September 26). This plan combines agreements signed by Uzbekistan and Rosatom in 2018 and 2024, and will construct two 1,000-megawatt and two 55-megawatt reactors at a site in the Darish district of the Jizzakh Province of Uzbekistan (see EDM, July 10, 2018; Kursiv, June 23; Times of Central Asia, September 29).

Tashkent is uncertain about the progress of its deal with Moscow because of international sanctions imposed on Russia over its full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Mirziyoyev discussed cooperation with Shen as a backup in case the agreement with Rosatom stalls. By holding talks with CNNC, Mirziyoyev has conveyed to Moscow that Tashkent is unwilling to delay work on the construction of its nuclear reactors and will seek alternative partners if Russia is unable to deliver (Eurasia Net, September 3; Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, September 14). Tashkent’s deal with Russia could be a risky path to nuclear energy, given the international sanctions and geopolitical tension that Moscow’s war against Ukraine has incurred.

Russia’s Rosatom, which is currently facing financial difficulties partly because of sanctions, has been playing a key role in developing Uzbekistan’s nuclear energy facilities. In 2017, Rosatom and the Uzbek Nuclear Energy Agency (Uzatom) signed a general cooperation agreement on nuclear energy. This agreement led to a September 2018 agreement to construct two VVER-1200 pressurized water reactors, each with a 1,200-megawatt capacity, at a cost estimate of $11 billion (The Times of Central Asia, September 29). The project aimed to reduce dependence on fossil fuel imports and support Uzbek industrial growth (Kursiv, September 5). In May 2024, during Russian President Vladimir Putin’s visit to Uzbekistan, Rosatom and Uzatom signed a new agreement to build a nuclear power plant (NPP) comprising six small reactors with a capacity of 55 megawatts each. The plant, as per the 2024 agreement, was to produce a total of 330 megawatts in the Jizzakh region and was scheduled for completion by 2033. When the Jizzakh deal was signed, the head of Uzatom, Azim Akhmedkhodjayev, praised Rosatom’s experience in implementing similar nuclear power projects (Kursiv, October 16, 2024). The updated 2025 agreement between Rosatom and Uzatom, which combines elements of the 2018 and 2024 plans, will involve the construction of two large VVER-1000 reactors and two small modular RITM-200N units in the Farish district of Jizzakh Province, Uzbekistan.

Globally, Russia is the key contractor offering assistance in the construction of nuclear power plants and nuclear fuel supply (see EDM, January 23, 29, June 25, July 15, September 5). The 2024 World Nuclear Industry Status Report showed that Rosatom was the leading builder and exporter of reactors at that time, operating in countries such as Bangladesh, the PRC, Egypt, India, and Türkiye (World Nuclear Industry Status Report, September 19, 2024; Cabar, November 20, 2024).

The PRC also cooperates with Uzbekistan to develop its nuclear energy facilities. The PRC’s small modular nuclear reactors have been the center of attention for Uzbekistan. In November 2024, the PRC’s CNNC and Uzbekistan’s Uzatom agreed to assess the possibility of deploying the PRC’s small modular nuclear reactors in the Central Asian country. They discussed cooperation in expanding uranium ore extraction, processing capacities, and the use of fuel in NPPs. In August 2024, a delegation of Uzatom officials visited the PRC, where they held meetings with energy companies and discussed acquiring PRC equipment used for cooling NPP equipment without water evaporation (Gazeta, November 6, 2024). In April, a trilateral meeting of the representatives from Russia’s Rosatom, the PRC’s CNNC, and Uzbekistan’s Uzatom assessed the capabilities of Shanghai Electric—one of the PRC’s leading manufacturers of power and turbine equipment for nuclear and thermal power plants. The meeting explored adapting the company’s turbine equipment to Uzbekistan’s nuclear power plant (Kun.uz, April 23).

Russia’s involvement in Uzbekistan’s nuclear projects and cooperation in nuclear energy could have repercussions and risks for Tashkent in the current geopolitical climate. Moscow’s war of attrition against Ukraine, its growing tensions with the United States and the European Union, and crippling sanctions imposed against it could create risks for Tashkent if it primarily depends on Russia for the construction and operation of nuclear energy facilities (Cabar.Asia, November 20, 2024).

Uzbekistan’s potential shift to cooperation with the PRC as an alternative to Russia would not be without risks. Frank Maracchione, an expert on the PRC’s engagement with Central Asia at the University of Kent, claims that “the PRC is now completely integrated into the region. There is no denying its overwhelming presence in Central Asia” (Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, September 14). If Tashkent depends on the PRC for its supply of spare parts, equipment, and technology for NPPs, access to those resources could hinge on the status of its relationship with Beijing. Such dependencies could pose security and sustainability risks to nuclear power projects (Cabar.Asia, November 20, 2024).

Russia is rapidly losing its influence and contracts in Central Asian countries due to sanctions and its distraction with its war against Ukraine. Questions are being raised about the reliability and sustainability of Moscow’s nuclear energy cooperation deals with Uzbekistan. The PRC is positioning itself as an alternative to Russian assistance with nuclear energy to increase its influence in Central Asia. Uzbekistan’s nuclear power capabilities face a precarious path ahead as Tashkent grapples with its cooperation with Moscow and Beijing amid the two powers’ shifting influence in Central Asia.