Uzbekistan Damages Regional Electricity Network

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 6 Issue: 202

By:

Uzbekistan recently officially announced that it will quit the Central Asia power system. Tashkent’s decision affects all countries in the region, with Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan suffering the most. The recent policy shift reflects the predicaments of Soviet period planning of energy supplies in the Central Asian region when –in general terms– upstream and downstream countries were presupposed to trade water for fissile fuel.

Uzbekistan will now use its new Guzar-Surkhan transmission lines that provide electricity from its domestic thermal power plants (TPP) to Surkhandarya oblast (www.stoletie.ru, December 2). While every Central Asian country wishes to separate from the Soviet-inherited regional electricity transmission network, the costs remain too high. Tashkent’s decision was mostly political and Uzbek TPP’s will experience severe problems in the delivery of the necessary amount of electricity during peak and non-peak hours. Unlike TPPs, hydropower plants in Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan are better able to regulate electricity supplies during daily fluctuations in the electricity demand.

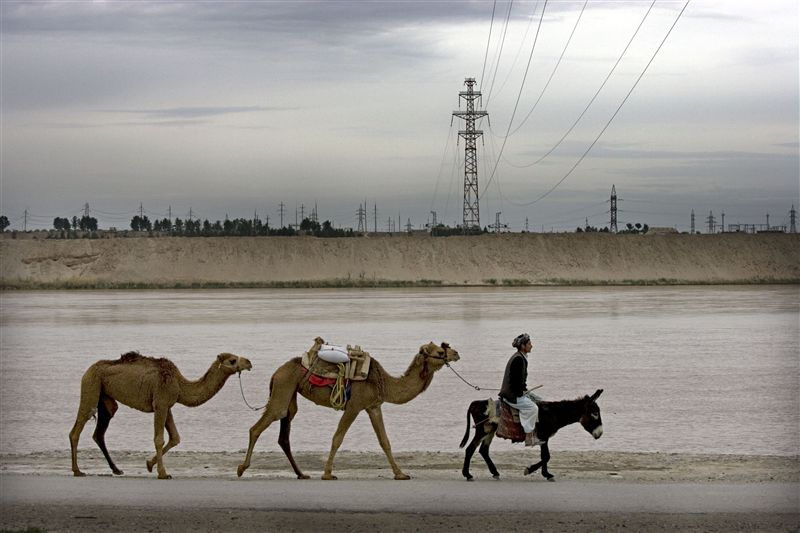

During the Soviet period Tashkent was in charge of controlling the Central Asian electricity network. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Central Asian countries were exposed to market economic conditions and each state had to survive on its own to secure sufficient energy. Upstream Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan have most of the region’s water resources, while downstream Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan enjoy natural gas and oil reserves.

Experts from the Soviet era still work in Tashkent and are able to consult the government on how to better separate national energy production from the regional network and thus gain more energy independence. Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, however, are more vulnerable and need to put greater effort into managing domestic energy security (www.prime-tass.ru, December 1). Turkmenistan, by contrast, was able to leave the regional energy network in 2003.

Tashkent has been warning its neighbors of its decision to separate from the regional network since it began the construction of several transmission lines several years ago. But real threats to cut the transmission lines were voiced only as late as the end of last summer: Tashkent warned Bishkek that it would also cut transmission lines (EDM, October 15).

Unlike most regional experts’ perceptions, Tajikistan will be unable to control water flow to Uzbekistan during the summer period, and is thus deprived of political leverage over Tashkent. Tajikistan’s Nurek dam’s storage capacity is not enough to keep more than one-third of the water flowing through Vakhsh River while other Amudarya tributary –the Panj River is not regulated at all.

Both Tajikistan and Uzbekistan have been seeking to increase independence from each other for several years. Both countries pursued the construction of high voltage transmission lines and substations. Dushanbe has also shown a clear determination to construct the Rogun dam on the Vakhsh River and, to Tashkent’s disadvantage, increase its own ability to generate power and increase control of water flows to Uzbekistan.

Tajikistan produces power in the south and used to transmit electricity to its industrial north through the Uzbek transmission system. Despite Tajikistan completing the South-North line Dushanbe still needs to connect its northern load centers to the new substation in Khodjent using 220 kV transmission lines to secure greater independence from Tashkent. Chinese investors are currently in the process of constructing these lines. Indeed, Tajikistan will experience electricity shortages this winter as earlier contracts on energy supplies with Turkmenistan through the territory of Uzbekistan are now undermined by Tashkent.

Meanwhile, Kyrgyzstan has reached an agreement with Kazakhstan on improving the reliability of its energy supplies (www.akipress.kg, December 2). Astana will supply Kyrgyzstan with humanitarian aid to buy coal from Kazakhstan in return for cheaper electricity and other business benefits. However, this agreement is rather short term. It will allow Kyrgyzstan to obtain sufficient amounts of coal for the Bishkek TPP, but not solve the country’s overall energy dependence issues.

As one expert from Tajikistan told Jamestown, “while being unable to regulate supplies of electricity during peak and non-peak hours, Uzbekistan will still manage the imperfect energy system by coercively cutting energy to its population during peak hours. Entire oblasts and cities might suffer from energy shortages” (December 2). Overall, the excess of electricity during non-peak hours and shortages during peak hours will negatively affect the entire electricity system.

However, Tajikistan has been trying to use maximum energy levels in the regional network thus provoking Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan to take swift action, while at the same time building its own lines and substations (www.ca-news.org, November 20). Unlike Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan has done virtually nothing to provide its own energy independence. Kyrgyzstan was unable to construct the Datka substation in the south, in order to increase independence from the Uzbek network. The delay in construction is caused by corruption and poor management of the energy sector, which usually relies on short term solutions.