Uzbekistan Resists Falling Under Russia’s Economic Hegemony

Uzbekistan Resists Falling Under Russia’s Economic Hegemony

In an unexpected move, Uzbekistan signed an agreement on joining the Russia-driven Free Trade Zone (FTZ) of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) on May 31, 2013. The agreement, seen as a precursor to more serious regional integration, such as joining the Customs Union and Eurasian Union, seems like a reversal of Uzbekistan’s policy of maintaining its independence from Russian hegemony. Uzbekistan has yet to ratify the FTZ to make it a full member. Full membership in the FTZ would entail abolishing Uzbekistan’s existing bilateral agreements with CIS countries that have been guiding regional trade since the breakup of the Soviet Union. The FTZ agreement will reduce the number of goods affected by import tariffs and will set a ceiling for the gradual cancellation of export duties (https://www.e-cis.info/zst.php). The FTZ already has six full members: Russia, Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Moldova and Ukraine. Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan have joined the agreement but, like Uzbekistan, have not yet ratified it.

Russia-wary Uzbekistan’s accession to the FTZ agreement can best be explained Tashkent’s fears that the free trade area’s current members might eventually act to restrict trade and labor migration on non-members while easing it for members (https://www.profi-forex.org/novosti-mira/novosti-sng/uzbekistan/entry1008166774.html). Indeed, Uzbekistan’s largest individual trade partner remains Russia, making up 18.1 percent of the Central Asian republic’s total trade volume. Moreover, Uzbekistan exports 48 percent and imports 42 percent of its goods to and from the CIS, collectively (https://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2006/september/tradoc_113461.pdf). Finally, according to the Russian Federal Migration Service, around 2.5 million migrants from Uzbekistan live and work in Russia. And the Central Bank of Russia estimates that, in 2012, Uzbekistani guest workers sent home $6 billion (around 10 percent of Uzbekistan’s GDP) (https://www.news.tj/ru/news/rossiya-vvedet-trudovye-vizy-dlya-migrantov-iz-sng). Therefore, tightening intra-CIS migration flows and trade between the regional bloc’s members would seriously impact Uzbekistan’s economy.

The United States, in the meantime, has been busy promoting regional trade in the framework of the New Silk Road Initiative, which by design includes Afghanistan. Matthew Murray, Deputy Assistant Secretary for Europe and Eurasia, at the US Department of Commerce’s International Trade Administration, visited Tashkent earlier this year. During his visit, Murray stated that in the fall of 2013, the Central Asian countries and the US will meet in Ashgabat to discuss mutual trade issues—in particular, the reduction of transaction costs that exist due to different customs rules and product certification issues (https://review.uz/ru/article/734). Whereas, in September 2013, the media reported that US companies with Uzbekistani partners are working on $4 billion dollars’ worth of investment and trade projects in areas of agricultural product processing and food production, the supply of breeding cattle from the US, the export of US equipment and technologies, as well as natural resource exploration in Uzbekistan. All this is a tangible indication of the United States’ growing involvement in Uzbekistan (https://www.gazeta.uz/2013/09/17/amerikanskie-kompanii-naraschivayut-investitsii-v-uzbekistan/).

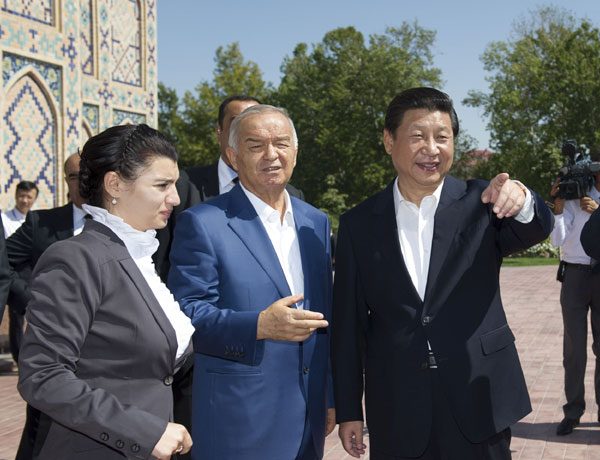

Intra-regional trade initiatives are supported and encouraged by the US. And though Russia does not openly hinder them, the financial support for significant infrastructure buildup across Central Asia will come from neither Moscow or Washington, but rather from Beijing. Indeed, China is now Uzbekistan’s second largest trade partner after Russia. Illustratively, Chinese President Xi Jinping proposed to develop a “Silk Road Belt” during his last visit to Tashkent on September 9, 2013, to boost economic cooperation, and stated that the resurrection of the Silk Road is a historic mission for Uzbekistan and China. President Xi added that Beijing is ready to cooperate in railroad, highway and air transportation projects to modernize the Silk Road (https://vesti.uz/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=38870). An important section of the Silk Road Belt, to which the Chinese president referred, would connect China by railroad with Uzbekistan via Kyrgyzstan. However, China and Kyrgyzstan failed to sign a final agreement on this project so far (see EDM, October 2). A recent plan by Uzbekistan to build a 129-kilometer Angren-Pop rail system is a missing link in this route but is planned to be completed in 2016. This route will allow China to open up additional transport links through Central Asia to access Europe.

No matter what initiatives Uzbekistan will take up in the long-run—whether it is ratifying the FTZ or jointly developing Silk Road trade routes to access Europe and Southeast Asia—it seems that Tashkent will be playing a greater role in accelerating international trade through regional economic cooperation. Uzbekistan, which does not want to limit itself to trading within the CIS, is looking for ways to develop economic links with countries outside the post-Soviet space. For example, this year, Uzbekistan requested to resume its accession process with the World Trade Organization (https://www.ustr.gov/countries-regions/south-central-asia/central-asia). In the meantime, however, as a signatory to the FTZ, Uzbekistan undoubtedly sees the CIS free trade area as an immediate economic benefit due to the country’s pre-existing, concrete ties with the region. For the near term, therefore, the CIS, as Uzbekistan’s biggest trade partner, will remain vital in the absence of any clear quick alternatives. Issues of infrastructure, along with transportation and trade procedure harmonization will not change overnight. But, as such alternatives appear, Uzbekistan may gradually try to substitute some of the historical links with its CIS partners. It is thus premature to predict that the country will succumb to Russia’s economic dominance merely through Tashkent’s accession to the CIS Free Trade Zone.