What is Xi Jinping Thought?

Publication: China Brief Volume: 17 Issue: 12

By:

Ahead of the 19th Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), scheduled to begin on October 18, media attention has focused on top-level personnel changes. While the selection of China’s new group of leaders is certainly important, recent announcement that current CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping’s political philosophies—Xi Jinping Thought (习近平思想)—are to be enshrined in the Party Constitution will have a tremendous impact on the political development of the Party and country (Xinhua, September 18). Since late 2016, President Xi, who is also Chairman of the Party’s Central Military Commission, has given himself the titles of “core leader” of the Party and “supreme commander”(最高统帅) of the country’s military forces. The promotion of Xi Thought as the official guiding principle of the party and state will mark another milestone in the president’s agenda of relentless self-aggrandizement (Radio Free Asia, August 17; HKO1.com, July 15).

Resistance to the elevation of Xi Thought to party-and-state dogma seemed evident from the communique of the Politburo meeting on August 31. The Politburo meeting, which was chaired by General Secretary Xi, indicated that the Party would abide by and carry out “the essence of General Secretary Xi’s series of important remarks and the new governance concepts, thoughts and strategies of the central party authorities (中央党).” On previous occasions, Party mouthpieces often attributed “governance concepts, thoughts and strategies” to Xi, the “core of the leadership.” By pointing out that these concepts, thoughts and strategies were those of the “central party authorities,” the Politburo seemed to endorse collective decision-making rather than the personal contributions of paramount leader Xi (BBC Chinese, September 1; Apple Daily [Hong Kong], September 1).

It is important to note, however, that changes in either personnel or dogma are still possible until the last one or two weeks before the Congress opens. Xi Jinping Thought has been cited officially or unofficially by top-ranked Xi protégés such as Politburo member and Director of the General Office of the Central Committee Li Zhanshu (栗战书) as well as the newly promoted Beijing party secretary Cai Qi (蔡奇). Moreover, the authoritative journal Party Construction Research (党建研究) stated in July that the party’s ideological and policy-related innovations since 2012 can be summarized as Xi Jinping Thought (Ming Pao [Hong Kong], August 5; Beijing Daily, August 4; HK01.com, July 15). Equally important is the fact that Xi has again asserted his formidable grip over power by engineering a reshuffle at the top echelons of the People’s Liberation Army. In August, he installed protégés and allies, Generals Li Zuocheng, Han Weiguo, Miao Hua, Ding Laihang as respectively the Chief of the Joint Chiefs Department, Commander of Ground Forces, Director of the Political Work Department, and Commander of the Air Force. Xi also sacked two top generals promoted by his predecessor, ex-president Hu Jintao. Former Chief of the General Staff Department Fang Fenghui and Director of the General Political Department Zhang Yang, were last month put under investigation for alleged disciplinary violations (Ming Pao, September 2; SingTao Daily [Hong Kong], September 1; South China Morning Post, August 23).

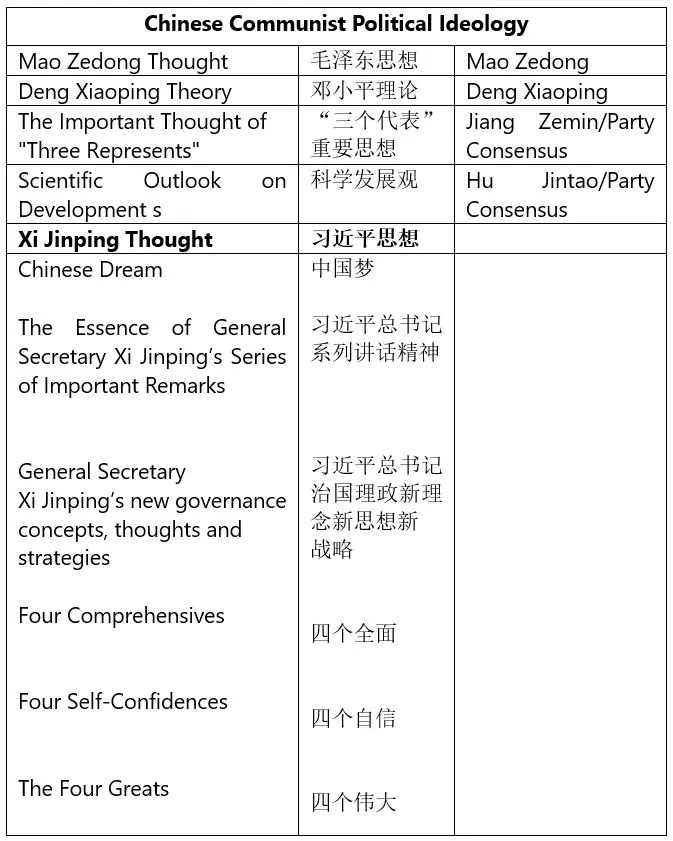

For a “leader core” who seems to be pulling out all the stops to consolidate his powers, the enshrinement of Xi Jinping Thought in the CCP Charter is a long-cherished goal. In the CCP’s 96-year history, the dictums and aphorisms of leaders ranging from Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai to Deng Xiaoping and Jiang Zemin have invariably been praised in the state media as “great, brilliant and monumental” contributions to official dogma as well as guiding principles for the party’s future. Yet only Mao’s ideas and pronouncements have been put together as Mao Zedong Thought, which is deemed on par with Marxism-Leninism. While Deng, the Great Architect of Reform deserved much of the credit for the “Chinese economic miracle,” his sayings were compiled as Deng Xiaoping Theory. In Party parlance, “theory” is at least one rung below “thought” in terms of authoritativeness and weight. While ex-president Jiang’s theoretical innovations, particularly the admission of private businesspeople into the party, are referred to in the party charter as “the important thought of the ‘Three Represents’,” Jiang’s name did not show up in the document. The “Three Represents” was thus considered to be a product of the collective leadership under Jiang. Ex-president Hu Jintao’s governance philosophy was cited in the CCP Constitution as the “Scientific Outlook on Development” but his name was also omitted. Also significant is the fact that while the theoretical contributions of various leaders are put into the CCP Charter only after their retirement, Xi Jinping Thought has been given this high honor at the end of his first five-year term (Citizen News [Hong Kong], August 23; Apple Daily [Hong Kong], August 19).

But what, exactly, is Xi Jinping Thought? And will its elevation the loftiest set of guiding principles for the Party-State spell a significant direction for major policies? Xi Thought is a compendium of dictums and slogans that the supreme leader has given since he took power at the 18th Party Congress in late 2012. Official media’s first summation of Xi’s ideology and statecraft, “the Essence of General Secretary Xi Jinping’s Series of Important Remarks” (hereafter “Important Remarks”), provides some useful insights. The authorities indicated at the Fourth Plenum of the Central Committee that party members must “deeply implement the spirit of General Secretary’s Important Remarks.” “Important Remarks,” said Party mouthpieces, encompass “new concepts, new ideas, and new strategies” in areas including political, economic and social construction, party and army construction as well as the cultivation of “environmental civilization.” But what exactly is new? Xinhua has noted that “Important Remarks” comprise “one core idea, and two fundamental points.” The core idea is Xi’s “Chinese dream,” which is a super-nationalistic narrative about China becoming a superpower. The “two fundamental points” refer to “comprehensively deepening reform and upholding the mass line” (China.com.cn, November 6, 2015; People’s Daily, July 17, 2014). Given the lack of concrete political or economic reforms in the past five years, as well as the gaping rich-poor divide among the populace, it is difficult to avoid the impression that Xi’s publicists are merely regurgitating hackneyed slogans. For example, the Chinese dream about the “renaissance of the Chinese nation” has been talked about by intellectuals since China’s first effort at Western-style political reform in the 1890s. “Upholding the mass line” or similar slogans such as “serving the people,” were first coined by Mao in the 1950s (Sichuan Daily, May 25; Thepaper.com [Shanghai], October 24, 2014).

Befitting a leader with no formal higher education and who likes to talk in populist tones, Xi’s words of wisdom are often expressed as catchy rallying cries. Specifically, Xi Dada—as he is fondly identified—likes to encapsulate his instructions in terms of four-fold criteria or objectives. In the wake of the Chinese Dream and Important Remarks, the propaganda machinery has since 2015 gone into overdrive extolling Xi’s “Four Comprehensives:” comprehensively building a moderately prosperous society, comprehensively deepening reform, comprehensively governing the nation according to law, and comprehensively governing the party in a strict manner. While this simple-to-remember dictum has been praised by the People’s Daily as a “strategic scheme for spearheading the renaissance of the [Chinese] people,” it breaks no new ground in Party ideology (Outlook Weekly, August 20; People’s Daily, September 8, 2015).

Instead of advocating new-fangled and sometimes controversial goals such as Deng’s revival of private enterprise or Jiang’s decision to seek fast-track accession to the World Trade Organizations, Xi is more interested in ways and means to preserve the party’s “perennial ruling status.” The “core leader” has repeatedly underscored the imperative of party cadres possessing Four Self-confidences” (四个自信), namely self-confidence in the path, theories, systems and culture marked by socialism with Chinese characteristics. Apparently inspired by the Maoist principle that the quality of cadres and soldiers was a matter of life and death for the Party, Xi demanded that officials must be cadres with Four Iron Qualities (‘四铁’干部) (People’s Daily, September 26, 2016; CCP News Net, December 14, 2015). This means that their faith and belief [in Chinese-style socialism] must be hard as iron; they must have ironclad discipline and a sense of responsibility as unshakeable as iron. In addition to the anti-corruption campaign, Xi has launched an ideological crusade against the “Four Evil Winds” or aberrant lifestyle among officials. This is a reference to combating formalism, bureaucratic work style, hedonism and a decadent lifestyle (Xinhua, September 9, 2016; People’s Daily, May 3, 2013).

Xi’s latest edict for strengthening the party and the country is described by official mouthpieces as the “Four Greats” (四个伟大).This is a reference to “waging great struggles, building great projects, promoting great enterprises, and realizing great dreams.” While the focus on great projects, enterprises and dreams are somewhat platitudinous, “waging great struggles” is reminiscent of Chairman Mao’s famous saying that “it is great fun to struggle against heaven, struggle against earth, and struggle against human beings.” According to Han Qingxiang, a professor at the Central Party School, “the four greats are a major theoretical innovation at the critical historical juncture of [China] developing a moderately prosperous country and launching a new great leap forward in socialist modernization” (Nanfang Ribao, August 21; People’s Daily, July 28).

According to a group of propagandists who use the collective pen-name of “Notes on Studying Xi” (学习笔记) “waging struggles” is nothing less than the quintessence of the supreme leader’s worldview regarding both Party and foreign affairs. Thus, Xi has raised the moral level of officials through his anti-graft operations and through political movements consisting of “ideological struggles” among senior cadres. In yet another genuflection to Mao, the “leadership core” also wants to wage struggles against colonialists and imperialists as well as against trade protectionism. Equally significantly, the Xi administration is committed to struggles against separatism, which includes pro-independence movements in Taiwan, Hong Kong, Tibet and Xinjiang (Qiushi [Beijing], August 17).

The emphasis on “great struggles”—or what Xi himself repeatedly calls “brandishing the sword”—could mean that the CCP administration might adopt more aggressive tactics toward handling its disagreements with the United States, Japan and ASEAN members which have territorial disputes with the PRC. Moreover, the new-found emphasis on fighting “Hong Kong separatism,” which was first mentioned by Xi when he visited the Special Administrative Region on July 1 to mark the 20th year anniversary of the handover of sovereignty to China, could mean that Beijing would redouble efforts to muzzle dissent in Hong Kong (Post852.com [Hong Kong], August 24; South China Morning Post, November 11, 2016).

Overall, it is not expected that the elevation of Xi Jinping Thought to official state dogma would augur well for political, economic or social reforms. The personality cult being built around the “core leader” as well as the emphasis on ideological purity among party cadres go against basic tenets of Deng Xiaoping. After having absorbed the lessons of the Cultural Revolution, the Great Architect of Reform insisted in the early 1980s that the party and country be run by a collective leadership, and that ideological hair-splitting should take a back seat to economic construction. Xi, however, has reiterated that “ideological and thought work”—a reference to brainwashing and Mao-style ideological campaigns—is “an extremely important task of the party” (BBC Chinese, June 27, 2014; People’s Daily, August 21, 2013).

Even more disturbing for reformers is Xi’s warning against “subversive errors” in the political or economic field. This was a reference to Gorbachev-style liberalization that might end up vitiating the power of the Communist Party. The fear that an overly reformist policy could indirectly lead to the party’s demise is behind Xi Dada’s famous “Theory of the Titanic.” Xi said in 2013 that a country as big as China could be compared to the Titanic: “if the Titanic really sinks, it will sink just like that.” On another occasion, Xi and his advisers were at pains to point out that irrespective of how effective or perspicacious a new idea or policy is, it could not be adopted if it was proven to be detrimental to the CCP’s monopoly on power. “If our Party becomes weak, scattered and [if it were to] even break down, what good will policy achievements do?” asked Xi (Southern Weekend, December 4, 2015; Jinghua Times, October 9, 2014).

Perhaps the biggest difference between Mao Zedong Thought and Xi Jinping Thought is that the former is oriented toward the future, and the latter is consumed with self-preservation. Mao, who compared himself to the proverbial foolish man who wants to move the mountain, wanted to “open up new heaven, new earth.” It is a supreme irony that despite China’s having emerged as a fire-spitting quasi-superpower, Xi’s obsession is to preserve the “perennial ruling party” status of the CCP as well as his status as undisputed leader. One of Xi’s most significant speeches was made in 2008, one year after his unexpected induction to the Politburo Standing Committee. The heir-apparent told a graduating class of the Central Party School, of which he was president, that the CCP’s ruling party status cannot be taken for granted. Xi had this to say about the fickleness of power: “Whatever we possessed in the past we may not no longer possess them now; and whatever we have now doesn’t mean we will have them forever” (Southern Metropolitan Daily, September 9, 2008). Instead of speeding up thorough-going reforms, Xi Jinping Thought could mainly serve as a rationale for the party to uphold its Leninist roots, and for its supreme leader to tighten his grip on power. Thus while the enshrinement of Xi Thought in the CCP Charter testifies to his ever-expanding power, it could also significantly bolster the essentially conservative nature of the strongman’s statecraft.

Dr. Willy Wo-Lap Lam is a Senior Fellow at The Jamestown Foundation. He is an Adjunct Professor at the Center for China Studies, the History Department and the Program of Master’s in Global Political Economy at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. He is the author of six books on China, including Chinese Politics in the Era of Xi Jinping (Routledge 2015) and most recently editor of the Routledge Handbook of the Chinese Communist Party (2017)