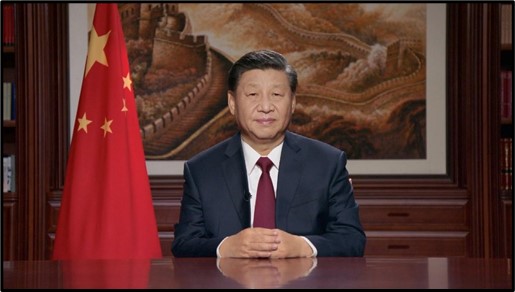

Xi Jinping Boosts the Party’s Control and His Own Authority

Publication: China Brief Volume: 21 Issue: 1

By:

Introduction

Under Xi Jinping, the leadership of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has initiated multi-pronged measures to ensure the success of celebrations marking the centenary of the establishment of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in July this year and planning for the 20th CCP Congress, scheduled for the second half of 2022. The accent is on preserving political stability and further consolidating the apparently unassailable authority of President Xi, who is also CCP General Secretary and Chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC).

“Be wary of dangers in the midst of stability” was the key theme of a Politburo Standing Committee meeting called on January 7. Xinhua noted that with this year being the centenary of the party’s establishment in 1921, cadres and party members must raise their levels of “political judgment, political awareness and [the efficacy of] political execution.” “[We must] in terms of ideology, politics and action maintain a high degree of unison with the party center (党中央, dangzhongyang) with Xi Jinping as the core,” Xinhua cited the Politburo communique as saying. It also quoted Xi urging CCP members to “use superior results to celebrate the party’s centenary” particularly in the areas of “administering the party with severity, ceaselessly building clean governance …and maintaining a good spiritual and work attitude” (People’s Daily, January 8; Xinhua, January 8).

Censorship of Party Members and the Media

In early January, the CCP passed a “Regulation on Safeguarding the Rights of Chinese Communist Party Members” (中国共产党党员权利保障条例, zhongguo gongchandang dangyuan quanli baozhang tiaoli) (hereafter “CCP Regulation”). The CCP Regulation would supposedly contribute to “intra-party democracy” by ensuring that the party center—headed by “core leader” Xi—would respect the individual rights of party members, including their freedom to critique policies and the working style of the leadership. Yet the CCP Regulation also warns that criticism of the party leadership must be made through designated channels. Members exercising their supervision function should do so “through channels of organization [departments]” (应当通过组织管道, ying dang tongguo zuzhi guandao) The CCP Regulation adds that party members are forbidden to “openly express views and suggestions that run counter to the theories, lines, objectives and measures of the party or the implementation of major policies of the party center” (Xinhua, January 5).

At the same time, The Cyberspace Administration of China published an updated draft version of its “Regulation on Internet Information Service” (互联网信息服务管理办法 [修订草案征求意见稿], hulianwang xinxi fuwu guanli banfa [xiuding caoan zhenqiu yijian gao]) (hereafter “CAC Draft Regulation”), which was first published in 2000. The CAC Draft Regulation clearly defines the proper functioning of an array of products such as search engines, instant messaging, websites, online payments, e-commerce and software downloads. New clauses have been added to target rampant forms of fraud on the internet, including identity theft and fake news (CAC.gov.cn, January 8; SCMP, January 8).

The publication of the updated CAC Draft Regulation coincided with the prosecution of several citizen journalists and professionals who exposed the origin of the Wuhan coronavirus in early 2020. The most famous and effective of these reporters, Zhang Zhan (张展), was recently sentenced to four years in jail for “picking quarrels and provoking trouble.” The unusually hefty sentence drew criticism from the United States and several other countries (Voachinese.com, January 5; BBC Chinese, December 29, 2020). Combined, these new censorship regulations signal that the regime’s control over civil society seems to have been unequivocally strengthened.

Enhanced Anti-Corruption Drive and Crackdown on the “Monopolistic Behavior” of Giant Private Firms

Compared with his first five-year term (2012-2017), when Xi established his reputation as a killer of “tigers” among corrupt officials, the recent anti-graft drive has been relatively quiet. Politburo Standing Committee (PSC) member Zhao Leji (赵乐际), who heads the country’s highest-level anti-corruption agency, the Central Commission on Disciplinary Inspection (CCDI), has assumed a much lower profile than his predecessor, Vice-President Wang Qishan (王岐山). From the last quarter of 2020 onwards, however, several officials and state-owned enterprise (SOE) chiefs with the rank of vice minister or above have been nabbed for taking ill-gotten gains from associates and friends seeking favors. They include the vice-mayor of Chongqing Deng Huilin (邓恢林); vice-governor of Qinghai Wen Guodong (文国栋); chairman of the China State Shipbuilding Industry Corp (CSIC) Hu Wenming (胡问鸣), and chief account of China Oil and Foodstuffs Corp (COFCO) Luo Jiamang (骆家駹). The four were kicked out of the party at the beginning of this year following investigation for economic crimes (China Daily, January 5; Caixin, October 27, 2020). On January 5, the nation was shocked when Lai Xiaomin (赖小民), former chairman of the state-controlled financial giant China Huarong Asset Management Corp., was given a death sentence for pocketing bribes totaling 1.8 billion RMB (a little under $278 million). Since the era of Reform and Opening, Lai’s case represents one of the very few instances of a vice ministerial-level cadre being sentenced to death for corruption (People’s Daily, January 6; RTHK, January 5).

Moreover, the State Administration for Market Regulation recently launched its potentially largest-ever anti-monopoly campaign against private enterprises, targeting in particular highly successful internet companies such as the Alibaba Group (China Brief, December 6, 2020). Last month, a commentary in People’s Daily pointed out that “monopolization impedes fair competition, distorts the distribution of resources, harms the interests of the market [economy] and consumers, [and] snuffs out technological progress.” The party mouthpiece added that China, which is a world leader in the digital economy, has a special need to “fight monopoly and ensure the healthy development of the [IT] sector by laying down regulations for the digital field so as to build a solid foundation for its further development” (People’s Daily, December 24, 2020). Yuan Jiajun (袁家军), party secretary of Zhejiang Province, which is the home base of Alibaba and a host of private tech companies, revealed that the anti-monopoly drive was “a policy made by the party center with Xi Jinping as its core.” “Zhejiang is relatively more developed in platform economics, online economy and fintech,” said Yuan, who is seen as a Xi protégé. “We must on the one hand demonstrate our innovativeness and vigor in these sectors and at the same time be at the front rank in their supervision and administration” (Zhejiang Daily, December 29, 2020; Apple Daily, December 29, 2020).

Intense speculation exists that the Xi leadership favors some form of the integration of SOEs and private enterprises, echoing the kind of “public-private co-management” (公私合营, gongsiheying) that was practiced by Mao Zedong in the 1950s (CGTN.com, October 20, 2020) This is partly driven by the increasing levels of debts accumulated by both SOEs and regional administrations. In the past year, Beijing has boosted the number – and power – of party cells in non-state firms (China Brief, September 28, 2020). Central authorities have also forced a number of profitable private firms to invite SOEs to acquire sizable chunks of their shares at below-market prices or at no cost at all. The best-known example took place late last year, when the famous Kweichow Moutai Co. Ltd. gave 4 percent of its shares—worth some 90 billion RMB ($13.8 billion)—to an SOE in Guizhou Province (The Paper [Shanghai], December 24, 2020; Finance.sina.com, December 23). Apart from securing a bigger share of the profits of private tech giants, such activities also boost the Xi leadership’s direct control over key sectors of the economy.

Conclusion: Dubious Efficacy of Beijing’s Tactics at Home and Abroad to Boost Nationalism and Party Control

Xi’s insistence on heading off dangers related to instability also includes ways and means to defuse challenges from the U.S., which is purportedly sponsoring an “anti-China containment policy.” Beijing has taken advantage of the partial power vacuum in American politics created during the transition of power from the Trump to Biden presidency to project both hard and soft power. In view of Biden’s widely anticipated strategy of forging a common front among democratic countries and regions such as the EU, Australia and several Asian countries to rein in Chinese expansionism, the CCP administration has quickly consolidated its economic collaboration with a host of nations through multilateral treaties such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) (China Brief: December 10, 2020; December 23, 2020). On December 31, 2020, Beijing and the EU concluded final negotiations for a EU–China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI). The CAI, which has yet to be ratified by European parliamentary authorities, is widely seen as an effort to drive a wedge between the U.S. and the EU, particularly in regards to the formation of a common policy against China (New York Times Chinese Edition, January 7; BBC Chinese Edition, December 31, 2020). The RCEP and CAI are also seen as a fillip to China’s potentially joining the Comprehensive and Progression Agreement on the Transpacific Partnership (CPTPP) (Ming Pao, January 3; Deutsche Wells Chinese Edition, December 30, 2020). Beijing’s apparent success in projecting power on the global stage is also geared toward promoting nationalism and pride in the country’s achievement, which is expected to be highlighted during celebrations of the CCP centenary this year as well as the upcoming 2022 Party Congress.

In the final analysis, however, much depends on the trajectory of the domestic economy, which has been hard hit by the pandemic. Even though the projection for GDP growth in 2020 by international organizations (including rating agencies) is between 1.8 percent to 2.5 percent, persistent unemployment issues coupled with high debt by overleveraged SOEs and local administrations remain a threat to continued recovery (Guangming Daily, December 15, 2020; Xinhua, September 18, 2020). Nearly two years ago, Xi warned in an early 2019 speech against “black swan” events breaking out in the country (China Brief, February 20, 2019). After the COVID-19 pandemic, the propensity for large-scale social unrest remains relatively high. Moreover, Beijing’s ability to invest in global projects like the Belt and Road Initiative, which is a major means for China to boost its international profile, has been badly hit by the country’s depleted central coffers (Radio French International, December 9, 2020; Ming Pao, December 9, 2020). Whether the CCP administration can use major events such as the party’s centenary or the 20th Party Congress to boost its prestige – and the authority of the party center’s “core” – remains a big question mark.

Dr. Willy Wo-Lap Lam is a Senior Fellow at The Jamestown Foundation and a regular contributor to China Brief. He is an Adjunct Professor at the Center for China Studies, the History Department, and the Master’s Program in Global Political Economy at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. He is the author of five books on China, including Chinese Politics in the Era of Xi Jinping (2015). His latest book, The Fight for China’s Future, was released by Routledge Publishing in July 2019.