China’s “One Belt, One Road” Strategy Meets the UAE’s Look East Policy

Publication: China Brief Volume: 15 Issue: 11

By:

From May 8 to 15, Dubai, the second largest state of the United Arab Emirates (UAE), hosted a first of its kind seven-day trade exhibition bringing together prominent government leaders, high net worth individuals and global corporate giants in Beijing. The week intended to showcase the opportunities Dubai presents for China and to promote a deeper understanding of Dubai as relations flourish between these two global trading centers (Zawya, March 18).

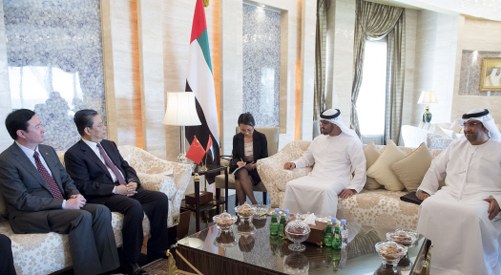

A series of high-level bilateral diplomatic visits between China and the UAE have already taken place in 2015. The latest came from a delegation led by Zhao Leji, a member of the Politburo of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Central Committee and Head of the CCP Organization Department, for a meeting with Sheikh Mohammad Bin Zayed Al Nahyan, Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi, the largest UAE emirate, and Deputy Supreme Commander of the UAE Armed Forces (Crown Prince Court, May 3). Zhao’s delegation was preceded by a visit to Beijing by the UAE’s Minister of State for Foreign Affairs Sultan Al Jaber to meet with China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi and Wang’s reciprocal visit to meet with Foreign Minister Sheikh Abdullah Bin Zayed Al Nahyan in Abu Dhabi, and Sheikh Mohammed Bin Rashid Al-Maktoum, the ruler of the emirate of Dubai (Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs [MFA], February 6; MFA, February 15; MFA, February 14).

At the top of China’s diplomatic agenda is the continued development of the bilateral strategic partnership established in 2012, and the promotion of the “Silk Road Economic Belt” and a “21st Century Maritime Silk Road,” otherwise known as the “One Belt One Road” or New Silk Road strategy, which is a “systematic project” to connect Asian, European and African countries more closely (MFA and Ministry of Commerce [MOFCOM], March 28). In concrete terms, China wants to construct an interconnected system of roads, railways, maritime transport and oil and gas facilities, cross-border power supply networks as well as other industrial, technological and economic initiatives to create an international trade and investment environment favorable to it (MFA and MOFCOM, March 28).

Beijing’s grand plan is to build this “Belt” and “Road” by seemingly integrating the development strategies of the countries along the routes (MFA and MOFCOM, March 28). Therefore, to integrate the UAE, as Foreign Minister Wang pointed out: China wants to combine its “One Belt, One Road” westward strategy with the UAE’s “Look East” policy, which seeks to increase the UAE’s share of trade and investment from Asia’s emerging economies as an attempt to diversify the local economy (MFA, February 15; MFA, February 14; Gulf News, April 8). Consequently, China is seeking to launch new fields of cooperation in the relationship, including high-speed rail, nuclear power, telecommunications and financial arrangements, in addition to existing cooperation in the energy and maritime sectors (MFA, February 14).

East Meets West in the UAE at Jebel Ali

Looking east, developing relations with China is amongst the foreign policy priorities of the UAE (MFA, February 14). As the recent Beijing exhibition shows, the UAE is actively lobbying for investment from Chinese enterprises, and whereas China is primarily interested in the UAE as an inter-regional trading and re-export hub—shipping goods from China to the Gulf and then onwards to North and East Africa and Europe—both countries’ current development strategies sync to some extent (The Zone Magazine, Issue 37, 2014). As the third largest re-export hub in the world after Singapore and Hong Kong, approximately 60 percent of China’s trade passes through Dubai’s Jebel Ali Free Zone (Jafza), the world’s largest free zone, and Jebel Ali port for re-export (Government of Dubai, 2012; Jafza CEO, November 18, 2014). Trade, including re-export between China and the UAE, reached $46 billion in 2013, a 14-percent increase on the $40 billion in 2012, which made China the UAE’s second largest trading partner after Japan. In 2014, bilateral trade volume is reported as hitting a new high of $54 billion, of which $48 billion was with Dubai (UN Comtrade Database; Chinese Embassy in the UAE, February 20). China, therefore, overtook India as Dubai’s largest trading partner last year (Gulf News, March 23).

Trade volume between Jafza and Chinese companies has also been increasing rapidly. In 2002, it stood at $934.3 million, and by 2011, it had reached $10.1 billion (The Zone, Issue 36, 2013). Consequently, today, China ranks amongst Jafza’s top trade partners, with growth in the relationship constant and set to continue as discussion is underway to further enhance trade ties (Jafza, March 12, 2014). A visit from the Chinese Consul General in Dubai, Tang Weibing, to Jafza last year was succeeded by a visit from a Chinese delegation of 20 businessmen representing diverse sectors of China’s economy (Jafza, March 12, 2014). Jafza currently hosts over 7,300 companies from 125 countries around the world, of which 238 are Chinese (Jafza, December 15, 2014). This latter figure is a substantial increase on the mere 15 Chinese companies established in the zone in 2002 (The Zone Magazine, Issue 39, 2014). In recent years, the number of new Chinese companies entering annually has been growing at a phenomenal rate. 22, 27 and 79 companies entered in 2012, 2013 and 2014, respectively (Jafza, December 15, 2014; The Zone Magazine, Issue 39, 2014). In 2014, of the 679 new companies that entered, 29 percent came from the Asia Pacific region, including 6 percent from China, compared with 7 and 20 percent from the United States and Europe, respectively (Jafza, May 3, 2015). Contrarily, in 2012, the biggest number of new investors came from the developed world, including 9 percent from the Americas and 27 percent from Europe, which compares to 21 percent from the Asia Pacific region, of which 5 percent were Chinese (The Zone, Issue 34, 2013).

With a long-term vision, expansion and global growth in mind, numerous leading state-owned enterprises (SOEs) are amongst the Chinese companies (The Zone Magazine, Issue 25, 2010 and Issue 29, 2011). These include China State Construction Engineering Corporation (CSCEC), China Railway Engineering Middle East, China Ocean Shipping Corporation (COSCO) and Haier, China’s largest home appliance brand (The Zone Magazine, Issue 36, 2013). One Chinese business man described the strategy as follows: “establish our Dubai branch; appoint a team to run the branch; find local people for local markets; and […] provide support to distributors and customers through Dubai” (The Zone Magazine, Issue 29, 2011). Hence, it is ambition that is driving Chinese investment. For Chinese companies, a presence in Jafza is viewed as a step out of the competitive domestic market, a stable gateway with little political risk to Middle Eastern markets and a good place to position themselves between East and West (The Zone Magazine, Issue 29, 2011).

Approximately 60 percent of Chinese companies present in Jebel Ali, including China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) and its subsidiary Petrochina, as well as SINOPEC Group and its first listed company Sinochem International, deal in the oil and gas sector (Zawya, April 7, 2014). Hardly surprising given that, in 2013, the Middle East supplied 52 percent of China’s crude imports, of which 4 percent came from the UAE (EIA, February 4, 2014). Following the signing of a strategic partnership between state-run Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC) and CNPC in January 2012, CNPC obtained a concession equating to a 40 percent share in a joint venture with ADNOC to work on upstream projects in the UAE (The National, April 29, 2012). This deal, while upending a decades’ long status quo of Western oil companies as the dominant foreign players in the UAE oil concession system, is demonstrative of the UAE’s “Look East” policy, which includes oil export market diversification and is thus well-matched to China’s growing energy needs (The Telegraph, April 29, 2014).

Developing an Alternative to the Hormuz Oil Chokepoint

In Fujairah Free Zone, at the eastern end of the Emirates, Sinopec, taking a 50-percent share in a joint venture with Singaporean Concorde Energy and Fujairah emirate, has constructed an oil-storage facility with a capacity of 1.16 million cubic meters, making it the largest oil storage facility in the Gulf; Sinopec will lease half (The National, March 14, 2013). The terminal’s location, adjacent to the port of Fujairah on the Gulf of Oman on the UAE’s Indian Ocean coast, lies 160 kilometers (100 miles) south of the Strait of Hormuz at the mouth of the Persian Gulf (The National, March 14, 2013). This geography makes it appealing to oil traders and tank operators as exports can circumvent the Hormuz chokepoint, reducing war risk shipping premiums levied for entering the strait as well as shipment times to Asia (Bloomberg, February 19; The Robert S. Strauss Centre, 2008).

Also with the Asian market in mind, the International Petroleum Company (IPIC), the investment arm of the government of Abu Dubai, which holds most of the UAE’s oil reserves, financed a 380-kilometer (230-mile) crude pipeline from Habshan onshore oil facilities in Abu Dhabi across land to Fujairah for export via the sea (Gulf News, July 16, 2012). With a contract valued at $3.9 billion, the line, including the oil terminal at Fujairah and offshore loading facilities, was constructed jointly by China Petroleum Engineering and Construction Corporation (CPECC), an affiliate of CNPC and China Petroleum Pipeline Bureau (Gulf News, July 16, 2012; hydrocarbons-technology). The pipeline was completed in March 2011 and reached its full capacity in 2012, transporting 1.5 million barrels per day (Gulf News, June 16, 2012; hydrocarbons-technology).

China Shipping Makes Waves in UAE Seas

Also on the Gulf of Oman, in 2014, privately owned Khorfakkan Container Terminal (KCT) received the first vessel of China Shipping Container Lines’ (CSCL) expanded joint service with the United Arab Shipping Company (UASC), co-owned by the UAE, Kuwait, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Iraq. The two carriers have signed a number of joint service agreements over the past few years connecting Asian ports with ports in the Middle East and Europe (UASC News, September 9, 2014). Khorfakkan is the only fully fledged operational container terminal in the UAE located outside the Strait of Hormuz, and having underwent expansion, CSCL’s increased usage of it similarly reduces the geopolitical risk factors associated with a strait closure, including pricing and transit times between North East Asia, Singapore, the Gulf and Northern Europe (Zawya, August 18, 2014; Gulftainer, September 2, 2009). Demonstrating further the importance attributed by China to its maritime trade with the UAE, the seventh of CSCL’s recently acquired 14,000 twenty foot equivalent unit (TEU) container ships also made its maiden call to Jebel Ali port, positioned at the western end of the free zone bordering Abu Dhabi emirate. As an addition to the Far East–Middle East service, it will serve the Jebel Ali-Tianjin trade route, which is the busiest route between the Far East and the Gulf region (The Shipping Tribune, March 15, 2012; Arabian Gazette, April 9, 2012).

Since 2001, CSCL has also been a partner of Dubai Ports (DP) World, a global terminal port operator that was previously Dubai Port Authority and currently the international arm of Jafza. [1] In 2014, a visit from the Chairman of Qingdao ports, Zheng Minghua, to Jafza led to the announcement of a strategic framework agreement between Qingdao Port Group and DP World, deepening further an existing partnership (Jafza, November 18, 2014). The agreement focused on continued collaboration in Jebel Ali port, the mothership port of DP World, and Mina Rashid port, located at the eastern end of Jebel Ali zone close to Sharjah emirate (DP World Press Release, November 23, 2014). The two marine terminal operators intend to increase trade between their respective ports by studying current liner services and trade volumes and by establishing a systematic approach to information sharing regarding port planning (Port Technology, November 24, 2014). A further objective is to connect the two ports by means of a railway that would pass through the Jebel Ali Free Zone, which adds another facet of multi-modal connectivity for Chinese exporters to use the UAE as a hub for distribution within the Gulf region (Jafza, March 12, 2014; Zawya, January 12, 2015).

The Limits of China’s Ambitions

The UAE has become an important commercial focal point for Chinese companies, and the recent high-level diplomacy has showcased China’s intensions to strengthen further ties (MFA, February 14). Yet with the Emirates having own corporations integrated into the global economy, the feasibility of China’s plans to incorporate the UAE into its “One Belt, One Road” initiative has some limits despite the UAE’s “Look East” policy. China Harbour Engineering Company previously failed to obtain the bid for construction of terminal four of Jebel Ali port and development of Chinese high-speed rail has generated little interest, as there are only short distances to be covered in the Emirates (Meed, September 17, 2013; Meed, March 25, 2013; Financial Times, July 31, 2013). Chinese companies have been described locally as focusing only on export and import activities and as wanting government contracts without connection to the local market and culture. Abdullah Al Saleh, undersecretary to the UAE’s Ministry of Economy said: that “is not the way we are doing business here” (Gulf Business, February 14). These criticisms will not stop Chinese companies from ambitiously pursuing their thriving trade relationship with the UAE, nor the Chinese government from positioning the UAE as a key node in its “One Belt, One Road” plan.

Notes

- Arang Keshavarzian. 2010. Geopolitics and the Genealogy of Free Trade Zones in the Persian Gulf. Geopolitics, 15(2): 271.