The Age of the Warlord Is Coming to an End in Afghanistan

By:

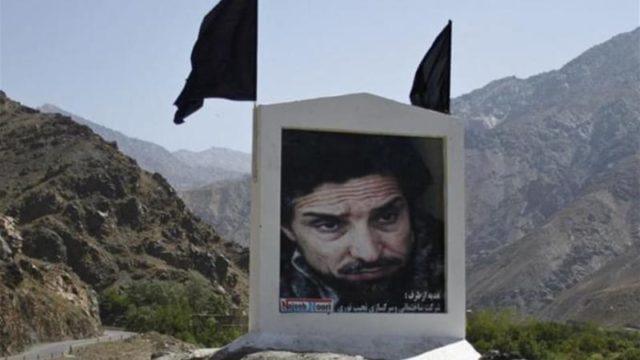

The age of warlords in Afghanistan may finally be ending. The beginning of the end started before Afghanistan attracted the world’s attention on September 11, 2001: thus, September 9, 2018, marked the death, 17 years ago, of Ahmad Shah Masoud, a Tajik commander who was assassinated by members of al-Qaeda posing as journalists (Tolo News, September 9, 2018). And as a bookend of sorts for this period, Jalaluddin Haqqani, another commander, died earlier last month, on September 3, 2018.

Both men were important figures in the war against the Soviet Union in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Haqqani rose to prominence as a beneficiary of support from the United States’ Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), the Saudi government, and Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) (Afghanistan Online, September 18, 2008). Whereas, Massoud repeatedly thwarted Soviet plans to invade the Panjshir Valley, north of Kabul (Afghanistan Online, November 18, 2007).

Although the two men were affiliated with national groups like the Northern Alliance and the Taliban, respectively, they were also quasi-independent warlords with their own following. During the Soviet occupation and subsequent Afghan Civil War in the 1990s, Massoud built up a personal army of fighters loyal to him (Afghanistan Analyst Network, May 30, 2014). Haqqani similarly built up his own network. In 1996, the latter man became an ally of the Taliban and provided this militant group with an important base in southeastern Afghanistan, where few of its members had connections (Afghan Analysis Network, September 20, 2012).

The two men’s deaths are representative of a long-term shift occurring in Afghanistan: throughout the country, warlords are becoming obsolete. Over the past two years, the Afghan government has acted against them, including the dismissal and forced exile of important northern commanders. General Abdul Rashid Dostum left Afghanistan for Turkey last year, after allegations of kidnapping and assault on a political rival (Tolo News, August 13, 2018). The Afghan Attorney General’s Office filed charges against him in court for the offense (Tolo News, July 28, 2017). And Atta Mohammad Noor, dubbed the “King of the North” for ruling Balkh Province as governor for 14 years, reached an agreement with the Afghan government to step down (Gandhara, March 21, 2018). President Ashraf Ghani ordered Noor to vacate the governor’s office in December 2017, but Noor initially refused to leave his power base (Tolo News, March 21). Abdul Karim Khudam, a Noor ally and member of a powerful political party, likewise refused to step down after being sacked by Ghani (Tolo News, February 19). Nevertheless, he eventually resigned days later after an agreement between his political party (Jamiat), and the national government (Tolo News, February 20). It is noteworthy that two northern governors were dismissed within months of each other.

The country’s remaining warlords are also losing their grip on power due to factionalism and their inability to control it. Although General Dostum returned to Afghanistan recently this year, he has lost control of his own political party. Dissidents from his faction, Jombesh, formed their own political grouping, New Jombesh, last year (Afghanistan Analysis Network, July 19, 2017). This formation is significant because Dostum had previously reacted violently to dissent within Jombesh. In one instance, his militia kidnapped and tortured another political rival who was preparing to mount a challenge to Dostum’s leadership within the party (Afghanistan Analysis Network, July 19, 2017). The only reaction to the break between old and new Jombesh has been public scorn from the former against the latter. Dostum supporters and “old” Jombesh members called the new party “Agents of the Palace” and accused them of being “affiliated with the government” (Afghanistan Analysis Network, July 19, 2017).

Independent agencies in Afghanistan have also contributed to the demise of the warlords by taking away an important source of their power—national office. Afghan warlords were once considered among the country’s most influential elites, having gained access to government facilities and jobs in the bureaucracies (Asia Times, May 14, 2018). Nonetheless, the Independent Election Commission of Afghanistan (IECC) recently announced that warlords will not be allowed to stand for elections (Tolo News, July 26). Already 25 candidates with links to non-governmental armed groups were removed from the list of parliamentary candidates (Tolo News, August 4).

Lastly, international organizations and European states have stepped up calls for justice against Afghanistan’s warlord class. In mid-August, the ambassadors for the European Union and Norway in Kabul said, in a joint conference, that the case against Dostum (for the assault on a political rival mentioned above) should be concluded via legal channels since he returned to Afghanistan (Tolo News, August 13). They added that “nobody should be above the law” and it is important that all Afghans work together peace, stability, and democracy throughout the country, based on full respect for the rule of law of all citizens (Tolo News, August 4, 2018).

The above actions are a dramatic turnaround in the government’s previous policy toward the warlords. Heretofore, the Afghan state utilized indigenous warlords as powerful allies against the Islamist insurgency. Thomas Rutting, a co-director of the Afghan Analysts Network, noted that private militias and strong men have flourished in modern Afghanistan because of their usefulness in the war against the Taliban (Afghan Analysts Network, March 20, 2015). Warlords were given money, governorships, cabinet positions, and even vice presidencies. In addition, they were afforded access to government facilities and jobs, as mentioned above.

The decline of warlordism is helping to strengthen state sovereignty and boosting President Ghani’s domestic authority. Last year, he pledged that his people will celebrate the sovereignty of law. The law is not sovereign when certain officials consider themselves untouchable or beholden only to the power of the gun, Ghani pointed out (Tolo News, March 15, 2017). The removal of Dostum, Noor and Khadim thus offers him an opportunity to appoint new loyal government officials who will contribute to consolidating Kabul’s control over the wider country. Now, there are fewer strongmen with militias and guns to prevent the writ of the government, especially in former warlord-held areas.

The end of the warlords will almost certainly impact the civilian population the most, promising to dramatically increase overall security. The United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) noted, in its 2014 “Annual Report on the Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict,” that there was a 194 percent increase in civilian deaths caused by warlord militia groups from the previous year (Afghan News Network, March 4, 2015). Most of those casualties were caused by fighting between rival pro-government militias (Afghan News Network, March 4, 2015). The UNAMA also noted the “impunity enjoyed by pro-government armed groups, which permitted them to commit criminal acts including assault, intimidation, and lack of protection for civilians and communities” (Afghan News Network, March 4, 2015).”

With the Ghani administration determined to remove warlords from power and the IECC’s use of legal tools to prevent them from gaining power at the national level, the chapter on Afghanistan’s warlords seems to be closing. Once powerful actors, they are increasingly being held accountable for their actions and can no longer wholly ignore the writ of the government or the chorus for justice by the international community. The recent twin deaths of Ahmad Shah Masoud and Jalaluddin Haqqani may thus come to symbolize the end of an era.