Russian Community Extremists Becoming the Black Hundreds of Today

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 21 Issue: 148

By:

Executive Summary:

- The Russian Community, a Kremlin-backed group of far-right Russian nationalists, has increasingly been attacking marginalized communities such as non-ethnic Russians, immigrants, LGBTQ+ individuals, and abortion doctors.

- The Russian Community works with the Russian security agencies, but the government is not yet ready to take direct responsibility for the Russian Community’s acts of violence, similar to the role of the Black Hundreds movement at the end of the tsarist period.

- The Russian Community has rapidly grown from a marginal group into the largest far-right organization in Russia. Its actions are radicalizing its opponents, increasing the likelihood of violent clashes between the oppressed, on the one hand, the Russian Community, and the state, on the other

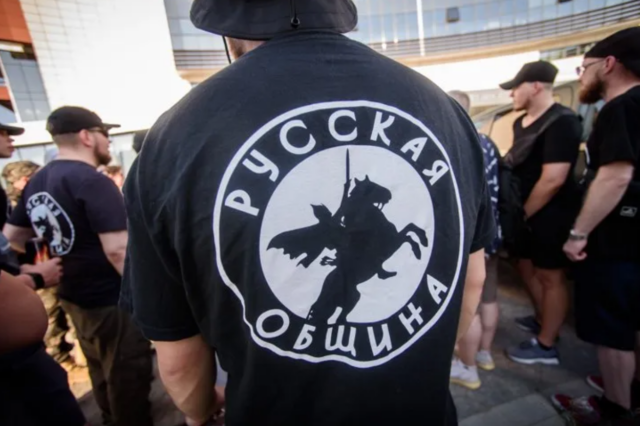

The Russian Community (Russkaya Obshchina), a radical far-right group prepared to violently attack anyone the country’s leader does not like with relative impunity, is rapidly on its way to becoming the Black Hundreds of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s Russia. The Black Hundreds was an infamous organization that was founded after the Revolution of 1905. The movement advocated for an all-Russian nationality and was particularly vocal against the influence of non-Russian groups, such as Jewish people (Encyclopedia of Ukraine, Vol 1. (1984) accessed on Encyclopediaofukraine.com). The Russian Community, a fairly new group organized in 2020, has reputed links to Konstantin Malofeyev, a supporter of Russian Orthodox conservatives and radical Russian nationalists. The group flew largely under the radar in Moscow and the West. They gained notoriety in 2023 after actively working with police across the North Caucasus to suppress ethnic protests and carry out violent attacks. Russian officials have been happy to benefit from the Community’s efforts but have not wanted to take direct responsibility for its violence. Russian specialists on far-right groups say, over the last few months, that the Russian Community has grown exponentially. The group has acquired an enormous online presence, opening increasingly active branches in major cities far beyond the North Caucasus, and attacking not only ethnic minorities but also members of the LGBTQ+ community, immigrants, and abortion doctors (Sova Center, July 11; Bumaga, September 24).

Unsurprisingly, these acts of violence are sparking comparisons with Hitler’s Sturmabteilung (SA) and their role in the rise of fascism in Germany by intimidating targeted minority groups. Simultaneously, and in a disturbing echo of the Black Hundreds, the Russian Community’s actions are radicalizing its opponents and increasing the likelihood of violent clashes between the Russian Community, the state, and these targeted groups. (On the Black Hundreds and some early parallels with the radical Russian right in post-Soviet Russia, see Donald C. Rawson, Russian Rightists and the Revolution of 1905 (Cambridge, 1995) and Walter Laqueur, Black Hundred: The Rise of the Russian Extreme Right (New York, 1993)). The Kremlin will undoubtedly exploit this kind of increased violence to mobilize the Russian people against those whom it deems as enemies. Said radicalization, however, will jeopardize the survival of the Russian Federation once Putin’s regime ends. All this considered, comparisons between the current Russian Community now and the tsarist-times Black Hundreds look less far-fetched and more accurate than many would care to believe at present.

In the last several months, clashes between members of diaspora groups, including Roma, Kurds, Central Asians, North Caucasians, and indigenous ethnic Russians (that predate Moscow’s control of their regions), have dramatically increased in frequency. Violence is the result of escalating actions by the Russian Community organization, which wants targeted groups expelled, suppressed, or assimilated. Some officials are worried that the Community’s actions could presage a full-scale ethnic war and have organized bodies to try to calm the situation (Radio Free Caucasus, August 27). Officials in many places, however, are following the Kremlin’s lead and openly cooperating with the Russian Community, viewing it as an ally that will help them control what is becoming an increasingly explosive situation (Radio Free Caucasus, August 7; Window on Eurasia, August 30, July 31).

The Russian Community’s role in such conflicts might have remained largely ignored in Moscow and the West had it not been for two developments. First, it has expanded both geographically and now victimizes a broader range of targets. Second, Chechnya’s Ramzan Kadyrov and numerous non-governmental leaders of non-Russian ethnic groups in the North Caucasus and other parts of the Russian Federation have been sounding the alarm and demanding that the Russian Community be stopped. According to the Bumaga investigative portal, the Putin regime does not like that the Russian Community is accurately described as “the largest far-right organization in the country” (Bumaga, September 24). The portal reports that the group has over 600,000 subscribers on its Telegram channel, over a million on YouTube, and another 440,000 on the social media website VKontakte. Through its social media, the Russian Community is speaking out and taking action against ever more groups, often far removed from non-Russian nationalities, who are at odds with Putin’s “traditional values.” Even though the Russian Community has become ever more closely aligned with Putin’s agenda on issues such as abortion, their alignment on certain issues has sometimes had the effect of offending more traditional Russian far-right groups who are wary of any group so obviously linked to the powers that be (Sova Center, July 11; T.me/antifaru, October 13, reposted at Doxa, October 13).

Of the areas where the Russian Community is active, their role in the increasing violence in the North Caucasus has represented the greatest cause for alarm. Kadyrov and other Chechen officials have called for the Kremlin to examine the activities of the Russian Community and possibly ban them altogether (Radio Free Caucasus, October 4; Window on Eurasia, October 11). Concurrently, Circassian activists are warning that the expansion of Russian Community activities into their homeland is destabilizing the situation. The Circassian National Front, for instance, reports that “the first branches of this nationalist group have opened in Kabardino-Balkaria (Nalchik) and Karachayevo-Cherkessia (Cherkessk)” (T.me/cirnatfront, October 3). Circassian commentaries warn of impending disaster if the Russian Community is not stopped, not only in Circassian areas but also in other non-Russian regions (Window on Eurasia, October 5; YouTube.com, October 14).

Adding to this sense of urgency is a decision by the Russian government to allow the heads of federal subjects to form their own militias (Window on Eurasia, September 27; see EDM, October 3). Many of these would likely be formed by recruiting Russian Community activists and veterans of Putin’s war in Ukraine—two groups that heavily overlap—leading to the intensification of Putin’s campaign against the non-Russian peoples. Some of the Federation’s republics, such as Chechnya, and other territories with national movements would almost certainly seek to combine such units with nationalists opposed to Moscow. This would set the stage for conflicts between ethnicities within the regions, between regions themselves, and between provincial authorities and the central government (Radio Free Caucasus, October 9). Today’s Russian Community could trigger a civil war just as the Black Hundreds movement played a key role in destabilizing Russian societies and normalizing violence ahead of the February and October Russian revolutions of 1917. Consequently, a group that has attracted little attention so far in the West deserves the closest possible security and condemnation, lest policymakers miss the potential core to a future violent uprising.