Moldova Narrowly Avoids Losing Presidency to Russian Trojan Horse

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 21 Issue: 162

By:

Executive Summary:

- Moldovan President Maia Sandu has won reelection in a hard-fought runoff, followed on the heels of an equally hard-fought referendum. The voting underscored chronic divisions in Moldovan society in both political and territorial terms.

- Russia and its local sympathizers seek to rehabilitate “Moldovan centrism,” a set of attitudes and policies balancing Moldova between Russia and the West. This approach predominated in Moldova until Sandu reoriented the country westward in 2020–2021.

- This presidential election was a dress rehearsal for the parliamentary elections due in July 2025. Moldova is a parliamentary republic, and those elections will determine the country’s future. Russia will aim to orchestrate a parliamentary majority of Moldovan “centrist” and Russophile groups.

Moldovan President Maia Sandu, the pivotal figure who reoriented Moldova westward four years ago, won reelection to a second term against Moscow-approved candidate Alexander Stoianoglo in a runoff on November 3. Sandu lost the vote on Moldova’s own territory, but the Moldovan diaspora’s vote in her favor in Western countries more than compensated for the in-country loss. Forcing an incumbent president into a runoff is seen as denting that president’s authority in the local political culture. All the more so when coupled with overreliance on diaspora votes to win the runoff. The inconclusive first round was accompanied by an ambiguous referendum to commit Moldova to the goal of joining the European Union (see EDM, October 31).

Sandu won the runoff by a healthy margin of 55.3 percent to Stoianoglo’s 44.7 percent in the overall vote, in a 54.1 percent turnout overall. On Moldova’s own territory, however, Stoianoglo won by 51.1 percent to Sandu’s 48.8 percent of the votes cast. Moldovan voters in Europe and North America favored Sandu by 82.8 percent versus 17.2 percent for Stoianoglo, thus deciding the election’s outcome, according to the Moldovan Central Electoral Commission’s final tabulation (Pv.cec.md, accessed November 5).

Four years ago, Sandu narrowly won the presidential election within Moldova, the diaspora vote magnifying her overall victory at 58 percent versus 42 percent for then-president Igor Dodon (see EDM, November 17, 18, 2020). Dodon’s Russian-oriented Socialist Party underwrote Stoianoglo this time, a far weaker candidate. They managed, nevertheless, to narrow the overall margin and even turn it around for an in-country win.

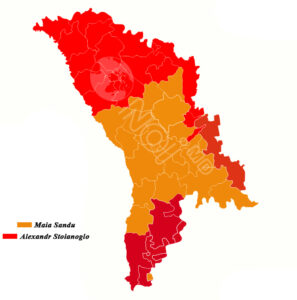

The electoral map of this runoff closely resembles that of the preceding presidential, parliamentary, and country-wide local elections in Moldova from at least 2016 to date. It shows the country divided into three compact zones by political preference: two “Red” zones in the north and south (plus Transnistria in the east) and a “Yellow” zone in the center (including Chisinau). Russophile parties, along with those balancing between Russia and Europe, predominate in the north and south. In contrast, Sandu’s Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS) and other pro-Western groups predominate in the country’s center.

Moldova’s Russophile parties are divided between two rival camps: Dodon’s Socialists with their local allies and the Pobeda/Victory bloc led by the Moscow-based tycoon Ilan Shor. Overseen by Russia’s presidential administration and Federal Security Service (FSB), respectively, the two opposition groupings differ markedly in strategies and tactics and do not cooperate politically on the ground in Moldova. Nor could the Kremlin persuade them to join forces ahead of Moldova’s presidential election.

Instead, Stoianoglo’s candidacy came about as a Socialist Party improvisation. Dodon is a habitual Kremlin visitor, and its presidential administration—most likely at the level of its deputy head, Dmitry Kozak—must have authorized Dodon to proceed with this candidacy. Stoianoglo does not need to contact the Kremlin himself. He is likely clean of any connections with Moscow in the past or present. He became, plausibly, an independent presidential candidate in Moldova, albeit running with the organizational support of the Kremlin-connected Socialist Party and counting on its electorate as his core support in the first round. He would then build upon and expand it in the runoff.

Neither Moscow, the Socialist Party, nor the candidate himself could have possibly expected to win the presidential election. Stoianoglo’s candidacy was announced belatedly in July, with little time to gain traction before the October 20 first round. Stoianoglo speaks faulty Romanian, has limited political experience, and no network of local supporters—not even in his native Gagauz autonomous territory, since he is a Chisinau Gagauz who built his career as a state prosecutor in the capital city. Had Moscow intended to capture Moldova’s presidency at this time, it would have sought a more serious candidate, first and foremost, a Moldovan from the titular nationality. Yet, despite those electoral handicaps, Stoianoglo came somewhat closer to success than anyone had expected.

Rather than a genuine candidate, Stoianoglo was cast as a Trojan Horse in the sense of introducing Russia’s geopolitical agenda into Moldovan elections. That agenda focuses on undermining public support for Moldova’s candidacy for EU membership. It could most effectively be undermined through politicians not identified with outright Russophile attitudes but, rather, with moderate, “balanced,” and “centrist” positions. In this sense, Stoianoglo acted as a typical representative of “Moldovan centrism,” which predominated in the country’s domestic and foreign policies until 2020. Several minor candidates also used this campaign to speak in that “centrist” vein.

Stoianoglo called for Moldovan “balanced policies between West and East,” first and foremost by restoring dialogue with “neighboring” Russia. He argued that Moldova needs Russian natural gas and Russia’s market for Moldovan agricultural products, notwithstanding that Moldova has broken those risky dependencies. Stoianoglo would reinstate direct flights between Moldova and Russia in the interest of Moldovan citizens regardless of international sanctions on Russia. He stood ready to meet with Russian President Vladimir Putin if the meeting’s agenda served Moldova’s interests. He would also readily go to Kyiv, Bucharest, Brussels, other European capitals, as well as Washington and Beijing. Professing to favor Moldova’s European course, he called for a boycott of the relevant referendum (see above). The candidate deplored “the conflict in Ukraine” as a humanitarian tragedy without criticizing Russia. He also called for strengthening Moldova’s neutrality by seeking international recognition (supposedly to safeguard against security arrangements with the West). Stoianoglo would initiate a dialogue with Transnistria’s leadership to restore confidence and establish a “fair status for the Transnistria region within Moldova.” He called for reforming the education system to ensure bilingualism in Russian and Moldovan/Romanian for all citizens—a throwback to the tenets of Soviet nationality policies in Moldova and elsewhere.

The candidate refrained from criticizing Shor and his tentacular organization during the campaign. Equally, he distanced himself from the Socialist Party “ideologically,” although recycling many of that party’s views. Stoianoglo’s campaign became effective after being joined by the highly resourceful Mark Tkachuk, formerly the gray eminence of Communist President Vladimir Voronin. Yet, Stoianoglo was never able to present a team of advisers or shadow cabinet to the public (Tribuna, July 15; Noi.md, October 27; Exclusiv TV, October 28; Reuters, October 29; Newsmaker, November 1; TASS, November 1, 4; Unimedia, November 3).

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and Moldova’s candidacy for EU membership made “Moldovan centrism” even more of an anachronism, yet it seems to have retained a sizeable audience that Moscow addressed via the Socialist Party and its presidential candidate in this campaign. Russia, the Moldovan government, and multiple opposition politicians viewed this presidential election as a dress rehearsal for the parliamentary elections due in July 2025. Moldova is for all intents and purposes a parliamentary republic, whereby the parliamentary majority forms the government. The president’s competencies are limited and, for the most part, ceremonial. When the pro-presidential party holds the parliamentary majority, however, the president can wield executive and moral authority informally, as is currently the case.

Russia will undoubtedly aim to change the Moldovan parliament’s composition in 2025 by supporting “centrist” and Russophile parties in the upcoming elections. Forging a parliamentary majority of Russophiles and centrists and a corresponding coalition government will be Russia’s main political objective in Moldova in 2025.