Sino-Russian Strategic Partnership Boosted by Syria Crisis

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 10 Issue: 164

By:

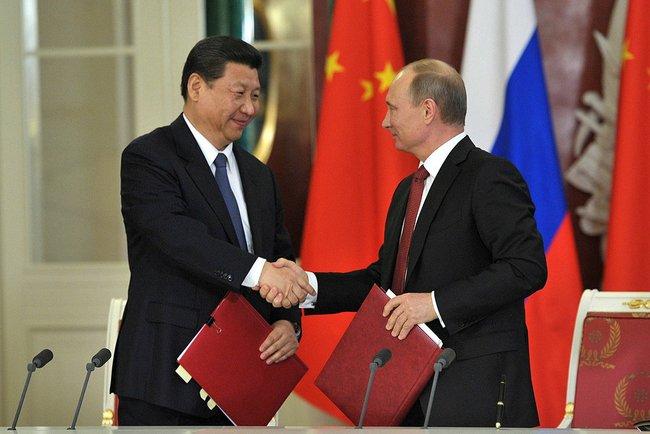

Considerable international media attention on the Syria crisis focused on the apparently deft handling of the diplomatic track by Russia’s President Vladimir Putin. Yet, Russian diplomacy, which succeeded in presenting Moscow as a critical player in the pursuit of a non-military option against Damascus, also contained an underestimated dimension: specifically the emergence of a de facto Sino-Russian alliance under cover of their strategic partnership and rooted in opposing unilateral action by the United States. Levels of coordination between Beijing and Moscow extended beyond repeatedly standing shoulder-to-shoulder in the United Nations Security Council in order to prevent a UN mandate for a military strike on the Bashar al-Assad regime. Evidence of this coordination also surfaced in the Bishkek Declaration issued at the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) summit on September 13 (RIA Novosti, September 15).

Russia’s apparently principled position during the crisis in Syria, following the use of chemical weapons in the suburbs of Damascus on August 21, yielded little surprise. Doctrinal and political opposition to US unilateral military action and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s (NATO) out-of-area operations have been persistent themes in Russian security thinking since the allied intervention in Kosovo in 1999. Moscow also adopted a very critical interpretation of the Arab Spring in terms of its expression of concern about stability in the Middle East and North Africa, as well as arguing that no foreign power possessed a right to intervene in the civil war in Syria. These themes were all present in the numerous official statements from the Russian political leadership in the aftermath of August 21, 2013 (Interfax, August 22–September 15). The second- and third-order consequences of Moscow’s successful forestalling of the strike option through its diplomacy will have a lasting impact on global affairs: these relate to the appearance of a virtual Sino-Russian alliance against the US on key issues.

On September 13, Putin used the opportunity afforded by the SCO summit in Bishkek to praise Syria’s decision to join the 1997 Chemical Weapons Convention. “We should welcome the decision of the Syrian leadership. I would like to express the hope that it will be a very serious step on the road to settlement of the Syrian crisis,” Putin told the summit. Unlike his experience of discord over the issue of options on Syria during the St. Petersburg G20 gathering earlier in the month, Putin could rely on the unity of the SCO and its core strengthening of Russia’s stance on the crisis by China (RIA Novosti, September 13).

On September 9, Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Igor Morgulov confirmed that Syria would feature on the SCO summit agenda. Morgulov added, “The positions of the SCO member states on the issue are very close; we all believe that a foreign military operation without the UN Security Council’s sanction is a violation of international law. I believe the Bishkek final declaration will include a consolidated position of the SCO states on the issue” (Interfax, September 9).

Consequently the heads of state of the SCO members (China, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan) gathered for the summit in Bishkek alongside the SCO’s observers (Afghanistan, Iran, Mongolia and India) and were joined by the secretary generals of the Eurasian Economic Community (EurAsEC) and the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), the executive secretary of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) and the UN deputy secretary general. On the sidelines of the summit, Putin met his counterparts from Afghanistan, Kyrgyzstan and Iran. The SCO Council of Heads of State approved a plan of action for 2013–2017 to implement the provisions of the Treaty on Long-Term Good-Neighborly Friendship and Cooperation between the SCO states and also signed the Bishkek Declaration. However, the summit was overshadowed by the Syria crisis, and occurred while the talks between US Secretary of State John Kerry and Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov were in progress in Geneva. Interestingly, Russian media, including the defense ministry’s Krasnaya Zvezda, emphasized that all members of the SCO, including China, support the early convening of a peace conference on Syria and the “initiative of the Russian Federation on the transfer of chemical weapons in Syria under international control” (Interfax, ITAR-TASS, September 13).

The Bishkek Declaration stated that the SCO stands for “the speedy overcoming of the crisis in Syria by the Syrians themselves, subject to the sovereignty of the Syrian Arab Republic,” and “launching a broad political dialogue between the authorities and the opposition without preconditions on the basis of the Geneva communique of June 30, 2012.” It added support for “the initiative to support the transfer of Syrian chemical weapons under international supervision with its subsequent destruction and the accession of Syria to the Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons and on Their Destruction” (https://redstar.ru/index.php/component/k2/item/11483-po-prioritetnym-napravleniyam).

Although Russia and China maintain a “strategic partnership,” they have eschewed any move toward forming a political-military alliance with mutual security guarantees. However, it is revealing to note carefully the chronology of how the initiative to disarm Syria’s stockpile of chemical weapons became known as “Russian,” as well as the Sino-Russian dialogue occurring prior to August 21 and as a precursor to the SCO summit. In fact, the idea was first advanced by Polish Foreign Minister Radoslaw Sikorski in late August, discussed by Putin and Obama in St. Petersburg on September 5 at the G20 summit, and not until September 8 did Moscow throw its full support behind the idea. On August 15, in Moscow, Nikolai Patrushev, the secretary of Russia’s Security Council, and Yang Jiechi, a member of China’s State Council, held the ninth round of consultations on strategic security. Several days before the chemical attack in Damascus, they exchanged views on North Korea and Syria and formulated plans to reach a joint position on the latter at the SCO summit (politikom.ru, September 5). Putin was able to exploit the gamble on mooting Syrian disarmament, knowing that Sino-Russian unity on Syria was guaranteed.

After the public backing of the disarmament plan by Putin, Patrushev said the US Congress had no authority to back strikes on Syria and again upheld the importance of the UN Security Council. “If a strike is delivered, then we can say that it is aggression against another state,” he added. Patrushev reiterated that Russia insisted on the need to resolve the situation in Syria by political diplomatic means and stated: “I believe that our position will be heeded in the end” (Interfax, September 9). It was ultimately the opportunism afforded by the Polish idea, and the Sino-Russian coordination in the background, that emboldened Putin to take the risk.