Russia Seeks China’s Support on Libya Crisis

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 8 Issue: 88

By:

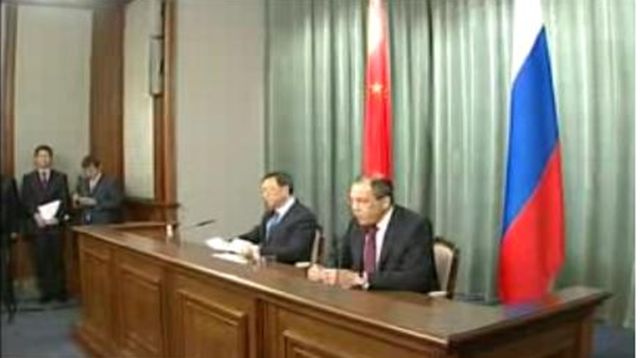

On May 6 in Moscow, President Dmitry Medvedev and Foreign Affairs Minister Sergei Lavrov each received Lavrov’s Chinese counterpart, Yang Jiechi. According to Lavrov at the concluding news conference, Russia and China would “coordinate their actions” in the UN Security Council and beyond to support the “soonest possible stabilization of the situation” in North Africa and the Middle East (Interfax, RIA Novosti, May 6).

Lavrov spoke more abundantly and aggressively than Yang during this event. Reasserting Russia’s known objections to NATO’s intervention in Libya, Lavrov added for the first time negative comments about Arab states and organizations that support that intervention in one way or another.

Utmost among Moscow’s concerns is the retention of its veto power, via the UN Security Council, over NATO or US operations. It was Medvedev who started the litany of complaints that NATO’s operation was exceeding the mandate of Security Council resolution no. 1973 on Libya. The Russian president used his visit to China on April 14 to air those complaints, hoping to draw support from the Chinese hosts in the first place. Moscow insists that any military measures that, in its view, overstep the UN mandate must first be submitted to the Security Council for Russian consent.

As Lavrov indicated again during Yang’s Moscow visit, Russia does not rule out its consent. It simply hints that its consent via a new resolution is subject to negotiation. Moscow professes concern that NATO countries may be planning a military operation on the ground in Libya. The Kremlin does not necessarily oppose a ground operation in principle. It does oppose NATO/US actions undertaken without prior negotiations in the Security Council with Russia, implying strategic trade-offs. Consequently, Medvedev and Lavrov are warning against “usurpation of the Security Council’s authority” – by NATO in this case.

Moscow’s next concern is to rehabilitate its own interpretation of state sovereignty and noninterference in the internal affairs of states. Russia and China are traditionally on common ground with this principle, although applying it differently. While Beijing accepts the self-restraint this principle implies, Moscow seeks to use it as a restraint on the West. In Libya’s case, Moscow criticizes those “taking sides” in favor of the Benghazi rebels and against Colonel Muammar Gaddafi, the two parties to a civil war. While stopping short of defending Gaddafi’s legitimacy, Russia objects to the calls for his removal from power. As Lavrov insisted during Yang’s visit, the UN mandate does not authorize Gaddafi’s removal or any regime change through “interference from the outside.”

In this context, Lavrov specifically criticized the Libya Contact Group’s May 5 decisions. The Contact Group’s meeting called for Gaddafi and his close circle to give up their power, decided to finance the Benghazi civilian authorities, and approved shifting funds from the Tripoli government’s frozen accounts abroad to the Benghazi authorities (“NATO Clarifies Goals In Libya,” EDM, May 6).

Such complaints can put Russia at odds with some influential Arab states on this issue. The Libya Contact Group includes, in one way or another, the Arab League, the Gulf Cooperation Council, the Islamic Conference Organization, and the African Union, alongside the UN, the US, NATO, and the EU. While the Western participants pushed through the Contact Group’s May 5 decisions, and although the Arab countries’ views are far from uniform on this issue, many Arab and other Muslim countries supported the Contact Group’s May 5 decisions. Lavrov cautioned the Contact Group against trying to substitute the UN Security Council or taking sides in this civil war.

Yang agreed with Medvedev’s and Lavrov’s calls for an immediate ceasefire and political negotiations between the Libyan sides, “without external interference.” Beijing is careful to endorse Libya’s territorial unity, unlike Moscow which remains ambiguous on this point (apparently seeing another possible bargaining chip in this issue).

China, like Russia, had abstained in the UN Security Council’s April 17 vote that authorized a limited military operation to protect Libya’s civilian population. On May 2, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs expressed concern over the operation’s escalation and a growing number of civilian casualties. It stated Beijing’s objections to any action not authorized by the UN Security Council, and it expressed hope for an undelayed ceasefire and negotiations (Xinhua, May 2).

Moscow and Beijing share an interest in protecting their UN Security Council veto powers from any erosion. Their common interests do not go far beyond this issue in the Libya crisis. Russia seeks to exploit the crisis against NATO (EDM, April 29, May 3). China, however, does not appear to be pursuing any such objectives.