Georgia Considers Opening its Border with Russia

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 6 Issue: 212

By:

On November 13, Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvili convened yet another session of his country’s National Security Council (NSC) with the participation of major parliamentary and non-parliamentary opposition parties. Boycotted by radical politicians, but highly appreciated by moderates, as a mechanism to conduct dialogue with the government and participate in the decision-making process, the so-called expanded sessions –whose topics are sometimes chosen even by the opposition– of the NSC has already become a tradition in a country facing internal and external challenges of enormous magnitude.

Russia adamantly pursues its policy of annexing 20 percent of Georgian territory in Abkhazia and South Ossetia, whose latest manifestation was the switching of telephone codes in Abkhazia from Georgian to Russian (Rustavi-2 TV, November 15), along with building concrete walls and barbwire fences to separate the occupied Georgian territories from the rest of the country (Jamestown Eurasia Blog, August 18, www.president.gov.ge, October 23). The Georgian government apparently feels that steps taken vis-à-vis Russia should be based upon broad multiparty consensus and close consultation with regional and international actors.

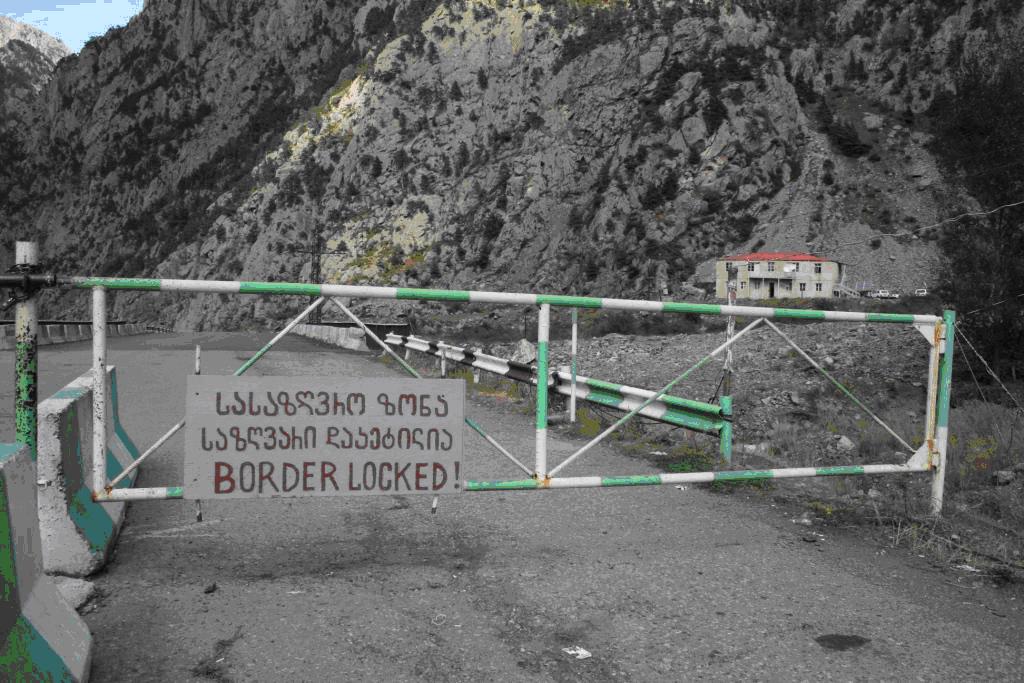

Reportedly, the opposition Christian Democrats requested that the NSC thoroughly discuss whether the only legal border crossing checkpoint with Russia at Zemo Larsi (Upper Lars) in the Kazbegi district should re-open. The Christian Democrats previously opposed opening the crossing, located at a high altitude in the Caucasus Mountains, expressing fear that Russia might use it “for new provocations against Georgia.” It was Moscow, and not Tbilisi, that shut the Zemo Larsi checkpoint in 2006 with an official explanation that the Russian side of the border needed to be renovated and re-equipped. In reality, this was part of its punitive measures imposed on a Western-leaning Georgia trying to consolidate its sovereignty.

Tbilisi recognized some economic damage as its trade with Russia was reduced, and the benefits from transit revenues for the use of Georgian territory were dramatically cut. Cross-border interaction between the local Russian and Georgian communities was stopped at Moscow’s will without warning. Armenia, Moscow’s only ally in the South Caucasus, suffered most. This was an unintended result of Russian measures against Georgia and was interpreted as unfriendly in Yerevan.

The Georgian public remains divided over the border issue. Some, like the Christian Democrats within parliament, fear that re-opening the border with a country that waged war against their homeland in August 2008 would create additional problems. Tbilisi has no diplomatic relations with Moscow and Georgians who oppose the move wonder how their government would be able to solve problems stemming from the regulation of transit and border crossing. Others believe that any issue in relation to Russia should be solved within a complex framework aimed at de-occupation of the two Georgian territories and the restoration of Georgia’s full sovereignty. Meanwhile, some fear that Moscow might be trying to penetrate into regions adjacent to the zone of occupation in Tskhinvali, namely, the Truso Valley located in Georgia’s Kazbegi district, to which Russia’s “South Ossetian” proxies have repeatedly extended their claims (Jamestown Eurasia Blog, September 29).

Tbilisi, on the other hand, has tried to alleviate such fears by saying that re-opening Zemo Larsi would not create any additional threats. Foreign Minister Grigol Vashadze, who emerged as the key speaker on the issue during the November 13 session of the NSC, has long argued that “in case of Russian aggression… [the Zemo Larsi border crossing] would have no role whatsoever,” pointing instead to economic advantages that opening the border would create for both Georgia and Armenia (Regnum, November 4).

The discussion within the NSC was preceded by consultations in Yerevan between the Georgian, Armenian and Russian delegations, although Tbilisi strongly denied Russian claims that the Georgian delegation held direct talks with the Russians on the border issue. The Georgian foreign ministry issued a special statement saying that “Georgian diplomats had no talks with their Russian colleagues in Yerevan” but “since the opening of the checkpoint at the Russia-Georgia border is very significant for the Armenian side, the consultations were held in Yerevan and we are ready to make a certain compromise to solve this issue to the benefit of Armenia” (Rustavi-2 TV, November 2; Regnum, November 3).

Following the debates in the NSC on November 13, Saakashvili’s National Security Advisor Eka Tkeshelashvili, said that the opening of the customs checkpoint at Larsi “will not pose threats.” She added that being “appropriate from the economic and social standpoints”…“this will serve both Georgian and Armenian interests” (Regnum, November 16). Although a final decision has yet to be taken, it seems the opening of the Zemo Larsi border crossing is only a matter of time and depends on how fast the trilateral technical and other issues will be resolved.

Unlike Armenia continuously expressing its desire to see the border crossing at Zemo Larsi opened, Moscow has until very recently strictly opposed the move and the dramatic change in its attitude deserves attention. One way to explain this shift might be a nascent Turkish-Armenian rapprochement and Moscow’s fear that without meeting Armenian requests concerning the opening of the border between Georgia and Russia it would be difficult to convince Yerevan that its alliance with Russia has no alternative. Moscow might also want to demonstrate to the West that it is moving toward normalizing its relations with Tbilisi and the occupation and de facto annexation of Georgian territories should not be seen as an obstacle that the Georgians might not eventually accept.

Zemo Larsi is located at the very beginning of the strategically important Georgian military highway leading to the capital Tbilisi. The highway itself is usually closed in wintertime when heavy snow and frequent avalanches impede safe passage. Interestingly, for reasons that are difficult to interpret, the Russians did not use the highway to advance their troops and armor during the war last year, while they moved deep into Georgia in the western and central parts of the country. But this does not mean that Moscow underestimates the significance of this passage now or in the past. It is worth recalling that both in 1801 and 1921 when Russia sent its troops to occupy Georgia the north-south Georgian military highway was heavily used for military purposes.