China’s Other Viral Crisis: African Swine Fever and the State Effort to Stabilize Pork Prices

Publication: China Brief Volume: 20 Issue: 5

By:

Introduction

Since January, much of the international news coverage surrounding the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been dominated by the story of the COVID-19 outbreak—a previously unknown coronavirus that first manifested in the central Chinese city of Wuhan in early December, and which has since rapidly proliferated throughout China and many other countries throughout the world (China Brief, January 29; Johns-Hopkins University, ongoing). The COVID-19 pandemic has largely crowded out international attention to another viral outbreak that Chinese authorities and farmers have been battling for eighteen months: African Swine Fever (非洲猪瘟, Feizhou Zhuwen), which throughout 2018 and 2019 devastated pig populations in both the PRC and surrounding countries. The virus has caused major disruptions to both supplies and the cost of pork, the primary staple meat in Chinese society. As such, it has had a significant impact on the Chinese economy, and has also given senior officials of the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP) reason to fear the potential impacts on “social stability” (社会稳定, shehui wending)—the CCP’s perennial overriding domestic concern.

African Swine Fever Devastates China’s Domestic Pig Population

African Swine Fever (ASF) is a highly-contagious hemorrhagic viral pathogen, with a rate of lethality that often runs near 100 percent among infected domesticated pigs. The virus is harmless to humans, although humans may act as a biological vector (i.e., carrier) of the virus. Other routes of transmission include: contact with infected pigs; ingestion of contaminated material (such as food waste, feed, or garbage); and ticks of the genus Ornithodoros. The virus is difficult to eradicate, as it possesses the ability to survive for long periods in feed products, porcine flesh or bodily waste, and vehicles and facilities used to transport or house pigs (OIE, undated; USDA, May 22, 2019).

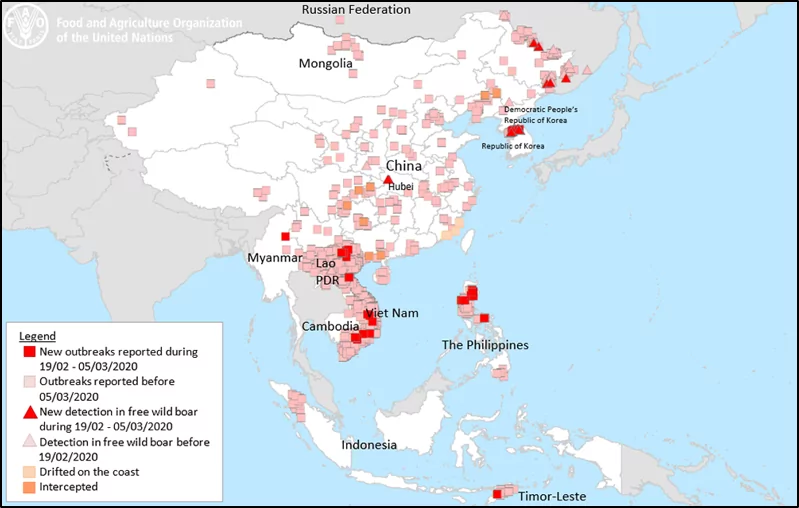

ASF first appeared in China in August 2018, with near-simultaneous outbreaks at multiple locations in central-eastern and northeastern China. The means by which the virus entered China remains a mystery; however, contaminated imported pork products, pig smuggling, contaminated feed, and tick bites have all been offered as potential explanations (Yicai Global, August 23, 2018; American Farm Bureau, September 7, 2018). ASF outbreaks have occurred in recent years in Eastern Europe and Russia (to include Siberia), with wild boar populations providing the primary vector of transmission—thereby making contact with migrating feral pig populations another plausible theory (CDC, April 2018).

Whatever the cause, the disease proliferated rapidly throughout 2018 and 2019, devastating China’s pig herds (often estimated to be half the global total). In April 2019, researchers with the Dutch firm RaboResearch predicted Chinese 2019 pork production losses of between 150-200 million pigs, or 25-35 percent of the country’s overall production (RaboResearch, April 2019). This massive figure is approximately one-and-a-half times that of overall annual U.S. pork production. [1] In December 2019, an English-language PRC press outlet indicated that “pork production declined at least 20 percent year-on-year” compared to 2018 (China Daily, December 31, 2019).

The Economic Impacts of African Swine Flu

As early as the end of August 2018, CCP propaganda authorities had reportedly begun to issue directives to media outlets and social media managers to refrain from further reporting on the ASF epidemic (China Digital Times, August 27, 2018). As with information restrictions regarding the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan (China Brief, January 17; China Brief, January 29), such restrictions likely facilitated the spread of the virus in its critical earlier stages. Other factors also played a part: many local administrations likely hid news of outbreaks for fear of negative economic impacts; and regionalized differences in market prices incentivized farmers to transport pigs (in some instances, infected pigs) to other areas, thereby further spreading the disease.

The massive fatalities among pig herds caused by ASF created an attendant rise in the cost of pork. In April 2019, the PRC’s official consumer inflation index hit a six-month high, due in part to a spike in pork prices—which, per official figures, had risen 14 percent since 2018, and more than 9 points in March 2019 alone (Yicai Global, May 9, 2019). Pork prices saw a particularly high spike in summer 2019: rising 17 percent in July, 46.7 percent in August, and 69.3 percent in September (Yicai Global, October 29, 2019). Although difficult to quantify, the rise in pork prices (as a prominent part of an increase in food prices overall) has likely further contributed to the broader macro-level slowdown in China’s GDP growth.

The ongoing COVID-19 crisis has also further exacerbated shortages of pork and other staple meats. As of mid-February, large-scale shipments of imported frozen pork, beef, and chicken—many of them coming from suppliers in North and South America—were reportedly backing up at port facilities, due to the fact that quarantines and transport restrictions were complicating normal routes and schedules for delivery (Bloomberg, February 17).

Pork Prices and the CCP’s Concerns for “Social Stability”

In autumn 2019, state propaganda authorities apparently decided that a more proactive response was necessary, and began to promote positive news stories to reassure the public about the availability and affordability of pork. In October, the Shanghai University of Finance and Economics issued an optimistic report indicating that—thanks to government actions—the price of pork would decline in 2020, and lower the consumer price index for foodstuffs along with it (Yicai Global, October 29, 2019). In late December, state media announced that, effective January 1, tariffs would be reduced for certain imported foodstuffs—to include frozen pork—as part of “efforts to moderately increase the import of daily consumer goods that are relatively scarce in the country… to better meet people’s needs” (Xinhua, December 23, 2019). Albeit speculative, it is quite likely that the need for increased pork imports played at least a contributing role in the PRC’s willingness to sign a phase one trade deal with the United States in January.

At the turn of the calendar New Year, state media ran optimistic articles about the recovery of pig herds and a drop in pork prices between November and December. State media also promised that supplies would be abundant for the Lunar New Year holiday season set to commence on January 25 (China Daily, December 31, 2019; China Daily, January 1). In the first two weeks of January, state officials released large-scale supplies of frozen pork onto the market, offering a total of 50,000 tons for public sale (China Daily, January 7). This was followed a month later by the announcement that a further 10,000 tons would be released for sale after February 7 (PRC Merchandise Reserve Management Center, February 4). These steps echoed measures taken in late September—just ahead of the October 1 ceremonies to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the PRC—when 30,000 tons of frozen pork were released onto the market to hold down prices at a politically “sensitive” time (China Daily, January 1).

These messages were largely crowded out by the COVID-19 pandemic crisis, which dominated both domestic and international news about China throughout the month of February. However, this narrative was picked up again beginning in late February, with announcements on February 27 and March 5 of new market releases of 20,000 tons of frozen pork scheduled to take place in each of the following weeks (PRC Merchandise Reserve Management Center, February 27 and March 5). This was accompanied by optimistic state press articles predicting a rapid recovery of herd sizes and meat production in 2020 (China Daily, March 5); as well as announcements of a drop in the country-wide price index for pork, due to the government’s “multi-pronged measures to boost supply, including increasing subsidies to restore hog production, releasing frozen pork reserves and expanding pork imports” (Xinhua, March 10).

Conclusion

The wildfire spread of African Swine Fever in 2018-2019 has not carried the tragic human toll of the COVID-19 coronavirus, but it still reveals much about the PRC’s governance model. Both viral outbreaks were almost certainly made far more severe by government-mandated restrictions on the disclosure of information to the public, which inhibited efforts to combat the diseases in their critical early stages. The response to the ASF crisis also provides yet another demonstration of how the ruling CCP seeks to manipulate economic forces to its own advantage—and how far China is from being anything close to a true market economy. Finally, it demonstrates the CCP’s continuing obsession with “social stability”—to the extent that even the price of pork dumplings is a matter of anxiety for the regime.

John Dotson is the editor of China Brief. For any comments, queries, or submissions, feel free to reach out to him at: cbeditor@jamestown.org.

Notes

[1] Per the U.S. National Pork Producers Council, a trade association representing pork farmers, average U.S. production is 115 million hogs, with a value of approximately $20 billion; and U.S. annual exports of pork and pork-related products total approximately 2.2 million metric tons annually (26 percent of overall production). See: U.S. National Pork Producers Council, “Pork Facts” (undated). https://nppc.org/pork-facts/.