Beijing Promotes “National Security” Measures to Seek Tighter Control Over Hong Kong

Publication: China Brief Volume: 20 Issue: 8

By:

Introduction: Beijing’s Personnel Appointments and Advocacy of “Patriotic Education”

Luo Huining (骆惠宁) was appointed in January 2020 as Director of the Liaison Office of the Central People’s Government in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (中央人民政府驻香港特别行政区联络办公室, Zhongyang Renmin Zhengfu Zhu Xianggang Tebie Xingzhengqu Lianluo Bangongshi) (hereafter “Central Liaison Office”), thereby placing him in charge of Beijing’s on-scene office for managing Hong Kong affairs. In taking up this role, Luo succeeded Wang Zhimin (王志民), who was likely replaced as a sign of Beijing’s displeasure with the failure to more effectively rein in anti-establishment protests throughout the second half of 2019 (HKFP, January 20).

Luo’s appointment was followed in February by the announcement that Xia Baolong (夏宝龙), the Vice-Chairman of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), would take up a concurrent appointment as Director of the State Council’s Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office (HKMAO). This move placed Xia in a key position for the management of policies towards Hong Kong, and also signaled a harder line by Beijing towards the restive territory (China Brief, February 20).

Throughout the widespread unrest seen in Hong Kong in the latter half of 2019, government spokesmen, state media outlets, and covert social media disinformation campaigns directed by the People’s Republic of China (PRC) have promoted a narrative that the “black hands” (黑手, hei shou) of hostile foreign powers were behind the protests (China Brief, September 6, 2019; China Brief, December 10, 2019). PRC outlets have advocated enhanced “patriotic education” (爱国主义教育, aiguo zhuyi jiaoyu) as one of the necessary solutions for the territory’s alleged problem of foreign subversion (China Brief, December 10, 2019). Some of these “education” measures are now being put into motion, as part of a wider crackdown by Beijing on dissent in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR).

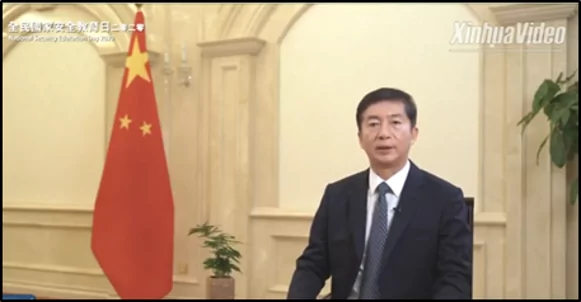

Beijing’s Representatives Send a Message on “National Security Education Day”

In mid-April, Luo Huining signaled efforts by Beijing to tighten control over the HKSAR by invoking the need for further “national security” measures in the territory. On the occasion of “National Security Education Day” (全民国家安全教育日, Quanmin Guojia Anquan Jiaoyu Ri) on April 15, Luo issued a video speech in which he stated:

In the nearly 23 years since Hong Kong’s return to the motherland, the system for safeguarding national security in Hong Kong has [revealed] shortcomings that could be fatal at critical moments. In recent years, foreign powers have deepened interference in Hong Kong’s affairs… [and thus we must] strengthen Hong Kong’s system for safeguarding national security. I believe that all friends who love the country and love Hong Kong will agree that we must take rapid steps to improve the legal governance system for upholding national security… and never allow Hong Kong to become a hazardous gap in the country’s national security (Xinhua/Youtube, April 16).

In thinly veiled comments clearly aimed at pro-democracy protestors, Luo further stated that “Many people have a rather weak concept of national security… if people are not punished when they break the law, there will be more copycat offences” in the future (RTHK News, April 15).

HKSAR Chief Executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor (林鄭月娥) (Carrie Lam) also issued a video message on April 15, in which she stated that Hong Kong “as an inseparable part of the People’s Republic of China, has a constitutional responsibility to safeguard national security, which also bears on the vital interests of Hong Kong residents…The HKSAR government must enhance its alertness against potential dangers even in times of peace” (Xinhua/Youtube, April 15).

Leung Chun-Ying (梁振英), Carrie Lam’s predecessor as HKSAR Chief Executive and a current Vice-Chairman of the CPPCC (Xinhua, March 13, 2017), was also cited in PRC state media as voicing support for these measures. As presented in a Xinhua commentary, Leung stated that “it is necessary to strengthen national security education as Hong Kong residents’ consciousness of the state was still weak;” and that “the HKSAR is also the country’s weak point in national security… Hong Kong’s opposition figures have become a pawn used by some Western countries in their rivalries with China” (Xinhua, April 15).

Aspects of Luo’s and Leung’s statements—in which Hong Kong is referred to as a weak link in China’s national security—are noteworthy in what they reveal about the mindset and anxieties of senior leaders of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Senior CCP officials likely believe their own propaganda about foreign subversion in Hong Kong (China Brief, December 10, 2019), and are clearly concerned that unrest (and the example of open protest) could spread to other regions of China. These anxieties have grown particularly acute in connection with the ongoing COVID-19 epidemic—which has seen both popular anger regarding the government response, and a CCP campaign to shore up the loyalty of security forces (China Brief, April 13).

Beijing Revives Controversies Surrounding Articles 22 and 23 of the Basic Law

A draft “Extradition Bill” was the major proximate factor animating the Hong Kong protest movement in 2019, but lurking in the background was another major political and legal controversy: the question of follow-on legislation to implement Article 23, an anti-sedition component of the Hong Kong Basic Law (China Brief, June 26, 2019). [1] This step has been advocated by pro-Beijing political actors dating back to the early 2000s, but has been feared by pro-democracy activists and civil society groups as a move that would provide pro-Beijing authorities with sweeping powers to suppress (and even criminalize) opposition political activity. [2]

“National Security Education Day” was accompanied by a renewed campaign to promote implementation of Article 23. In an April 17 article, Global Times asserted that “external forces have utilized the freedom in Hong Kong to concoct many anti-government protests to render Hong Kong anarchy [sic] and materialize it as a base for destabilizing the central government’s rule of the whole of China;” and that the “black hands” of the United States in organizing the unrest meant that “enactment of Article 23 is of great urgency” (Global Times, April 17). On April 23, Erick Tsang (Tsang Kwok-wai, 曾國衞), the HKSAR’s newly-appointed Secretary for Constitutional and Mainland Affairs, stated that “Article 23 is a constitutional duty of the HKSAR… it is not a matter of whether it should be done, it is a matter of when” (HKFP, April 24).

At the same time that pro-Beijing actors were playing up one article of the Basic Law, they were downplaying another. Article 22, which is intended to ensure Hong Kong’s autonomy, states that “No department of the Central People’s Government… may interfere in the affairs which the [HKSAR] administers on its own in accordance with this Law” (Hong Kong Basic Law, adopted April 4, 1990). On April 17, the Central Liaison Office issued a statement that Hong Kong’s autonomy was “authorized by the central government”—and that the central government, as “the authorizer,” maintained “supervisory powers over the authorized.” It further asserted that the Central Liaison Office (under direction of Luo Huining) and the PRC State Council Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office (under direction of Xia Baolong) are “authorized by the central authorities to handle Hong Kong affairs,” to include the correct interpretation and implementation of the Basic Law and of the “One Country, Two Systems” framework. Per this statement, the two bodies “are not what is referred to in Article 22 of the Basic Law, or what is commonly understood to be ‘departments under the Central People’s Government’” (VOA, April 18). Therefore, the Liaison Office effectively declared Article 22 null and void, and asserted an unlimited right to intervene in the territory’s affairs.

Arrests of Hong Kong Opposition Leaders

The announcement of the “national security education” drive was also followed in quick succession by punitive measures taken against Hong Kong opposition figures. On April 18, fifteen prominent figures from the territory’s democracy movement were arrested by police for involvement in “illegal assemblies” during the protests of 2019. In reference to the arrests, PRC state media stated that “months-long violent protests in Hong Kong severely hurt social stability and hindered economic development in the region, for which these riot leaders and [their] behind-the-scenes puppet masters should be held mainly responsible” (Global Times, April 18).

The arrested persons were: Jimmy Lai Chee-Ying, publisher of the Apple Daily newspaper; barrister Martin Lee Chu-ming; Legislative Council (LegCo) member Leung Yiu-chung; former LegCo members Yeung Sun, Lee Cheuk-yan, Albert Ho Chun-yan, Leung Kwok-hung, Au Nok-hin, Sin Chung-kai, Cyd Ho Sau-lan, and Margaret Ng Ngol-yee; and activists Richard Tsoi Yiu-cheong, Raphael Wong Ho-ming, Figo Chan Ho-wun, and Avery Ng Man-yuen (SCMP, April 20).

The arrests have drawn broad international condemnation. Chris Patten, the last British colonial governor of Hong Kong prior to the 1997 handover, stated that “the arrest of some of the most distinguished leaders over decades of the campaign for democracy and the rule of law in Hong Kong is an unprecedented assault on the values which have underpinned Hong Kong’s way of life for years” (HKFP, April 21). The U.S. State Department issued a statement that “the United States condemns the arrest of pro-democracy advocates in Hong Kong… Beijing and its representatives in Hong Kong continue to take actions inconsistent with commitments made under the Sino-British Joint Declaration that include transparency, the rule of law, and guarantees that Hong Kong will continue to ‘enjoy a high degree of autonomy’” (U.S. State Department, April 18).

Conclusion

The rapid succession of developments in mid-April should not be viewed in isolation; rather, they are part of a pattern of increasingly assertive steps by Beijing to tighten its control over Hong Kong, and to suppress the anti-administration, pro-democracy opposition movement. In the wake of last year’s protests—which sometimes turned violent in terms of property destruction, clashes between protestors and police, and assaults on citizens by pro-administration triad gangs—the narrative of “national security” may be expected to play a greater role in the central government’s efforts to assert tighter control over the territory.

Following the mid-April actions, Beijing may make a brief tactical retreat—as it has often done before— to gauge reactions in both Hong Kong and the international community. However, longer-term, the CCP will maintain its steady campaign to erode the HKSAR’s independent institutions, to assert selective and self-serving interpretations of the Hong Kong Basic Law, and to pressure the opposition into silence. The April campaign for “national security education” in Hong Kong is likely a harbinger of further actions to come.

John Dotson is the editor of China Brief. For any comments, queries, or submissions, feel free to reach out to him at: cbeditor@jamestown.org.

Notes

[1] Article 23 states that the HKSAR “shall enact laws on its own to prohibit any act of treason, secession, sedition, subversion against the Central People’s Government, or theft of state secrets, to prohibit foreign political organizations or bodies from conducting political activities in the Region, and to prohibit political organizations or bodies of the Region from establishing ties with foreign political organizations or bodies” (Hong Kong Basic Law, adopted April 4, 1990).

[2] In an op-ed published in the Washington Post after his April 18 arrest, barrister Martin Lee Chu-ming warned that the “vague standards” regarding sedition in Article 23 “are designed to protect the Chinese Communist Party and undermine core freedoms of Hong Kong, such as freedoms of religion, assembly and the press—including the reporting of pandemics that embarrass Beijing.” He further warned that implementation of the law could threaten international freedom of the press, on grounds that “under the Article 23 national security legislation, international publications operating or just distributing in Hong Kong could face prosecution for sedition.” [See: Martin Lee, “I Was Arrested in Hong Kong. It’s Part of China’s Larger Plan.” Washington Post, April 21, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2020/04/21/i-was-arrested-hong-kong-its-part-chinas-larger-plan/.]