Examining China’s Organ Transplantation System: The Nexus of Security, Medicine, and Predation / Part 1: The Growth of China’s Transplantation System Since 2000

Publication: China Brief Volume: 20 Issue: 8

By:

Editor’s Note: For many years, stories have circulated about alleged instances of involuntary organ harvesting in the People’s Republic of China—to include alleged instances of prisoners of conscience being first medically screened and then executed for their organs, with senior Chinese Communist Party (CCP) officials acting as either the medical or financial beneficiaries of organ transplant procedures. Many, though not all, of these accounts have been connected to alleged abuses directed at members of the Falun Gong spiritual movement, or other groups repressed by state authorities. Due perhaps to the lurid and disturbing nature of these accounts, and the difficulty of confirming them amid government suppression of information on the issue, the veracity of these alleged accounts of organ harvesting has long been left as an unresolved question.

Matthew P. Robertson, research fellow with the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation (VOC) and a PhD candidate in political science at the Australian National University, is engaged in an effort to direct analytical rigor towards this controversial topic, which has long been a marginalized issue on the sidelines of diplomatic and human rights discourses connected to the PRC. Mr. Robertson is the author of a detailed report on the topic published in March 2020 by VOC, available here.

In this article, the first part of a planned three-part series in China Brief, Mr. Robertson details the development and expansion of China’s policy architecture and medical infrastructure for organ transplants over the past two decades. The second part, to appear in our next issue, will examine the available evidence as to whether prisoners of conscience and targeted ethnic minorities in the PRC have been made subject to extrajudicial killing as part of this system of organ harvesting and transplantation. The third and final part, to appear in a near-future issue, will examine the ways that PRC authorities have sought to leverage influence over international medical organizations in order to suppress broader exposure of this issue.

Introduction

In late February and early March this year, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, official Chinese media reported two impressive medical feats: the Wuxi People’s Hospital near Shanghai, and the Zhejiang Medical University’s First Affiliated Hospital, both performed dual lung transplants for coronavirus patients. This was indeed a “World First!”, as one headline put it (Beijing Daily, March 1). While the news itself was noteworthy, so were the extremely short waiting times for the organs: Dr. Chen Jingyu, China’s most well-known lung transplant surgeon at the Wuxi People’s Hospital, managed to acquire compatible lungs from a healthy donor in Guizhou Province within five days of the patient being transferred to his hospital (China News, March 1). Similarly, surgeons at Zhejiang Medical University’s First Affiliated Hospital acquired lungs within three weeks for a March 2 transplant, after “scouring the country for a donor” (Beijing News, March 2).

These extremely short waiting times for procuring organs are unusual when compared to other countries, where waiting times are often measured in months or years. They speak either to an extremely efficient matching system from hospital-based, voluntary donors in the People’s Republic of China (PRC)—something that countries with advanced organ donor systems are often unable to achieve, let alone achieve in the midst of a pandemic—or else they indicate a captive population able to be executed on demand to provide organs. Based on the information at present, it is impossible to tell which explanation is true for these two cases. However, there are many reasons to find the rapid nature of such organ procurements suspicious.

For most of the last two decades, China’s transplantation system has been tightly linked with its security apparatus: nearly a quarter of authorized transplant hospitals are military or paramilitary (NHFPC, February 11, 2018). China is also the only country to systematically source organs almost solely from prisoners (Human Rights Watch, August 1994; Lancet, March 3, 2012). In 2015, the PRC claimed that it had reformed its transplant system, and officials promised that prisoners would never be used again (New York Times, December 4, 2014). Prior to that, it was clear that prisoners were being killed on demand: waiting times for transplants were only weeks, days, and sometimes even hours, meaning that execution and transplantation were being closely choreographed. There has been intense controversy about the identity of those prisoners—whether death row prisoners only (as claimed by China since 2006), or prisoners of conscience also.

Given that an organ transplant surgery can cost tens of thousands of dollars (TV Chosun, July 16, 2018), there is an obvious incentive for transplant hospitals and surgeons to perform transplants. The use of prisoners as an organ source involves only minimal expenditure for medical examinations. Thus, while some prisoners may be funneled to labor camps and in-prison sweatshops, a smaller number can be directly monetized via the procurement and trafficking of their organs. Furthermore, access to organ transplants appears to be one of the medical benefits available to officials in the ranks of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s nomenklatura. [1]

The central questions when examining China’s organ transplantation system at present include: Is the trade in human organs in China still continuing? At what scale? How successful has the PRC been at reforming its abusive practices? How strong is the evidence that prisoners of conscience have been, and continue to be, exploited as an organ source? And how deeply involved in these activities is the CCP itself—including its armed components of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and the People’s Armed Police (PAP)?

The Growth of the Transplant System—Without Growth of a Known Source of Organs

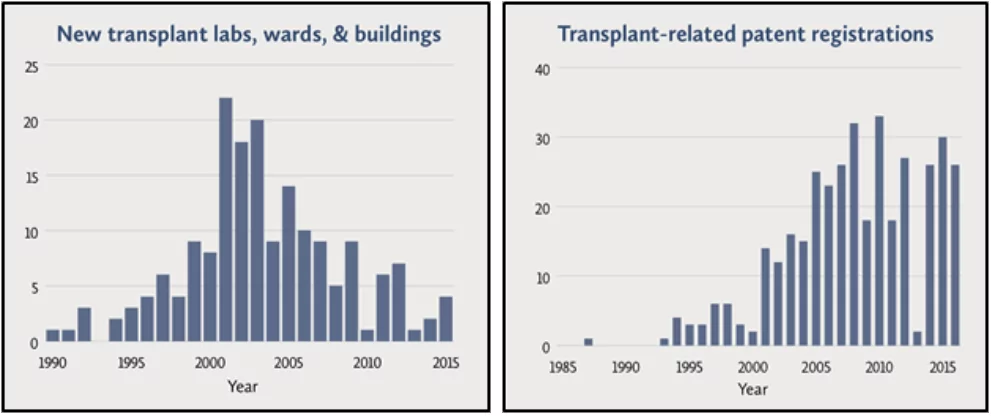

When examining the trajectory of China’s organ transplantation system over the last 20 years, a number of key findings emerge. The first is that the system began a precipitate expansion in the year 2000. This is clear both from anecdotal statements by Chinese transplant surgeons, as well as in the raw data able to be gathered from Chinese hospital websites. A leading Chinese surgeon with state ties told domestic media that the year 2000 was a “watershed” for China’s transplant sector, with liver transplants growing by ten times between 1999 and 2000, and tripling again by 2005 (Southern Weekend, March 26, 2010). A recent report by this author, commissioned by the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation, gathered nearly 800 data points from over 400 hospitals that confirmed such growth (VOC, March 10).

This data shows that the number of hospitals performing transplants grew from less than 100 in 1999, to nearly 600 in 2004, to a maximum of 1000 in 2007, according to Chinese media reports. Thousands of new transplant surgeons were also trained, with a total of nearly 10,000 documented transplant personnel by 2014. New patent registrations on transplant technologies grew rapidly after the year 2000, as did the number of hospitals reporting their first ever liver, lung, and heart transplants. (The growth in hospitals reporting new kidney transplants was more modest, because death row prisoners had long been used as a kidney source.) In the early 2000s, dozens of hospitals built new transplant research laboratories, wards, or entire buildings. The government also began subsidizing its domestic immunosuppressant industry.

The second finding, as mentioned above, is that transplants began being performed on-demand. This is evident in the country’s own liver registry annual reports, which were removed from the internet after researchers found the information. The 2005 and 2006 versions of these reports show that, respectively, 29% and 26.6% of all liver transplants (where the timing of surgery was noted) were performed on an emergency, rather than elective basis (2005 CLTR, February 12, 2006; 2006 CLTR, December 31, 2006). This means that after the patient presented at hospital with liver failure, a new liver—healthy and with a compatible blood type—was procured within one to three days. The removal of a liver attends the death of the donor. In the absence of a voluntary donation system, this can only plausibly be explained by the pre-screening of prisoners who are executed on demand.

The third finding is that China’s official explanation for the source of its organs does not account for what we are able to observe through a direct, if necessarily incomplete, study of the transplant system itself. Indeed, the official explanation for the source of organs has shifted as international pressure has increased. In 2001, a PRC spokesperson said the claim of organ sourcing from prisoners was “vicious slander” (New York Times, June 29, 2001). In 2006, this denial was softened to a revised claim that death row prisoners were used “in only a few cases” (Xinhua, April 10, 2006). By 2012, the authorities claimed that organs had been coming almost solely from death row prisoners all along (Lancet, March 3, 2012). Since 2015, the claim has again been that organs come from voluntary donors only.

When comparing the growth of the transplant system with the characteristics of the death penalty system, however, it emerges that there is a significant disconnect. The PRC is highly secretive about its death penalty numbers, but scholars who study the issue agree almost unanimously that the number of official executions in the criminal justice system has been in a long-term decline since the early 2000s, and that major reforms to the approval process for executions led to a precipitous decline in sentences beginning in the year 2007. [2] This took place when the PRC Supreme People’s Court resumed authority to review and approve every death sentence, rather than leaving the matter in the hands of provincial courts. Judicial insiders told Chinese media outlet Caixin that the drop in executions was so large that they dared not report it, lest the public think they were lying (Caixin, December 18, 2016).

Continued Growth of the Transplantation Medical Architecture

Despite this, China’s transplant apparatus continued to grow. In 2007 the largest organ transplantation center in Asia, a 14-story building, opened at the Tianjin First Central Hospital. It was originally planned to hold 500 transplant beds, but this was expanded to 700 even before it opened. It then reported operating at full capacity, before adding a further 300 beds in 2013 (Chinese Journal of Integrated Traditional and Western Medicine in Intensive and Critical Care, February 2006; Tianjin Daily News Online, September 5, 2006; China Construction Network, October 21, 2009; enorth.com.cn, June 25, 2014). The transplant surgeon leading this expansion, Dr. Shen Zhongyang, also founded the transplant center of the People’s Armed Police General Hospital in Beijing (Armed Police General Hospital, September 11, 2006).

From 2010 to 2012 the PLA’s 309 Military Hospital, which treats the CCP elite, expanded its transplant bed capacity by 25%, and grew its profits by 800% (Xinhua Military, February 28, 2012; 309 Military Hospital, November 17, 2010). Other major transplant centers also expanded, such as the Third Affiliated Hospital of the Sun Yat-sen University in Guangdong, which nearly tripled its transplant beds between 2005 and 2016 (Health News, December 4, 2005; The Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University, probably March 2016); while the Shanghai Renji Hospital doubled its transplant beds from 2004 to 2006, then tripled them again by 2016 (People’s Daily Online, June 23, 2006; Renji Hospital, probably 2016). These are only a few cases, which illustrate a much larger trend.

It is difficult to reliably estimate the volume of organ transplants implied by all this activity. Researchers have adopted a variety of approaches, primarily in the form of extrapolating from limited available data, or assuming that mandated minimum transplant volumes are upheld. These estimates suggest transplants in the range of 60,000 to 100,000 annually from the period of 2000 to 2015. [3] Another approach is simply to triangulate official public claims, which results in an estimate of 30,000 transplants annually in many of the years during this period (VOC Report Appendix 4, March 10). While the actual number is unknown, it appears to be far greater than can be accounted for by death row executions, which were estimated at a few thousand in 2013 (Dui Hua, October 20, 2014).

This apparent discrepancy leaves open a critical question: If a system of voluntary donations cannot explain the availability of healthy organs on short notice, and if the number of death row executions is significantly lower than the number of transplants, then what is the source of these organs?

This article will continue with “Examining China’s Organ Transplantation System: The Nexus of Security, Medicine, and Predation / Part 2: Evidence for the Harvesting of Organs from Prisoners of Conscience,” to appear in our next issue.

Matthew P. Robertson is a research fellow in the China Program at the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation and a doctoral student in political science at the Australian National University. His dissertation research examines the political logic of state control over and exploitation of the bodies of Chinese citizens, with a focus on the case of the organ transplantation industry.

Notes

[1] The CCP’s Healthcare Committee (保健委, Bao Jian Wei) has often maintained a leading organ transplant surgeon as chair or vice-chair since the 1960s. Most recently, Dr. Huang Jiefu has served as chair of the committee (Phoenix News, March 14, 2013). More generally, see: Wen-Hsuan Tsai, “Medical Politics and the CCP’s Healthcare System for State Leaders,” Journal of Contemporary China 27, no. 114 (2018): 942–55.

[2] This literature is reviewed in Matthew P. Robertson, “Organ Procurement and Extrajudicial Execution in China: A Review of the Evidence” (Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation, March 10, 2020), 27–30; 32–34, https://www.victimsofcommunism.org/china-organ-procurement-report-2020. Specific sources to consult include Susan Trevaskes, “The Death Penalty in China Today: Kill Fewer, Kill Cautiously,” Asian Survey 48, no. 3 (June 2008): 393–413; Hong Lu and Terance D. Miethe, China’s Death Penalty: History, Law and Contemporary Practices (Routledge, 2009); and Moulin Xiong, “The Death Penalty after the Restoration of Centralized Review: An Empirical Study of Capital Sentencing,” in Death Penalty in China: Policy, Practice, and Reform, ed. Bin Liang and Hong Lu (Columbia University Press New York, NY, 2016), 214–46.

[3] Kilgour, David, Ethan Gutmann, and David Matas, Bloody Harvest/The Slaughter: An Update (International Coalition to End Transplant Abuse, April 30, 2017). https://endtransplantabuse.org/an-update/.