Directions Forward for Chinese Rare Earths After the Two Sessions

Publication: China Brief Volume: 21 Issue: 5

By:

Following heightened U.S.-China tensions last year, the Chinese Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) issued the “Draft Regulations on Rare Earth Management” (稀土管理条例(征求意见稿), xitu guanli tiaolie (zhengqiu yijian gao)) on January 15. The new regulations propose stricter management of China’s rare earths industry, including quota management for mining, smelting and separation; stricter enforcement of environmental protection, new project investment approval procedures; and import and export management, describing rare earths as being “of irreplaceable significance for the transformation of traditional industries…and the advancement of national defense science and technology industries” (Xinhua, January 22). Shortly after the public comment period for the Regulations ended, MIIT issued its first batch of total control indexes for rare earths in 2021, mandating an 84,000 ton quota for mining, which marked a 27 percent increase from 2020 (MIIT, February 19). In 2020, China’s rare earth exports hit a five-year low amid the ongoing pandemic and increased demand from domestic industries.

Analysts were quick to note that whereas previous regulations were mostly focused on production, the new regulations seek to centralize Beijing’s control over the “entire industrial chain,” from production and refining to product transport and export. The regulation establishes a tracking system for rare earth products and states that companies shall abide by national laws and regulations for foreign trade, including a new national Export Control Law aimed at regulating the export of sensitive materials and technologies that went into effect on December 1, 2020 (Nikkei Asia, January 16; China Briefing, February 25).

Background

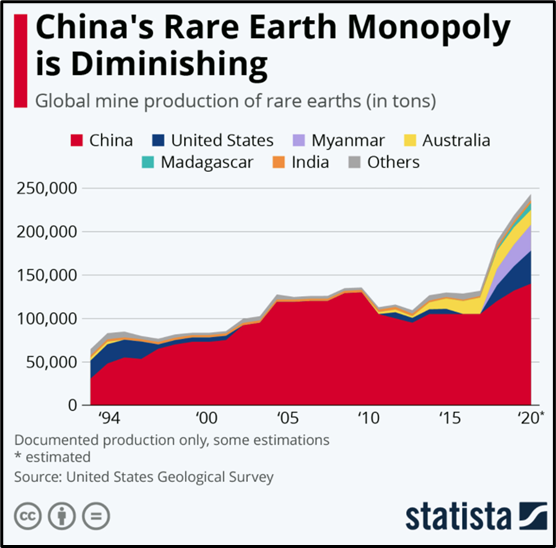

Rare earths, which usually refer to a basket of 17 minerals that are vital for high-tech manufacturing, have applications in emerging technologies such as high-powered magnets used in wind turbines, drones, electric vehicles (EVs), and energy-efficient batteries. They are also critical to the defense industry’s manufacturing of hypersonic aircraft, missiles, and radiation-hardened electronics. Heavy rare earths, defined as having a comparatively higher atomic weight, occur less commonly in nature—in particular dysprosium, yttrium and terbium face low supply even as they become increasingly important in the development of strategic technologies such as laser, satellite communications, and military control systems. China today accounts for more than 60 percent of global rare earth production, following decades of state investment in this strategic sector (China Brief, October 8, 2010). In addition to investing heavily in mine production around the world, China also dominates the rare earth refining process, with one Japanese analyst estimating that no currently operating rare earths processing facility does not involve Chinese investment of some kind (Nikkei Asia, January 16). In 2019, China produced roughly 85 percent of the world’s rare earth oxides and approximately 90 percent of all rare earth metals, alloys, and permanent magnets (China Power, September 24, 2020). But China’s position in the rare earths supply chain is neither absolute nor secure. Although China has the largest known deposits of rare earths, Brazil, Vietnam, and Russia also possess significant untapped resources. Both the United States and Australia have ramped up their production of rare earths since 2010, although the U.S. still exports raw materials to China for processing after closing down its last domestic rare earths processing facility in 2002 (Defense News, November 12, 2019). Myanmar and Madagascar have also started to produce significant amounts of rare earths, and China relied on Myanmar for more than half its heavy rare earth concentrates in 2020 (Reuters, February 10).

As China has sought to develop its high-tech economy, its consumption of rare earths has outpaced the scale of production. Following a crackdown on illegal mining in 2018, China’s domestic rare earth output declined and the state became a net importer of rare earths for the first time since 1985 (Caixin, March 16, 2019). In a recent press briefing, Xiao Yaqing, Minister of MIIT, noted that local populations have pushed back strongly against environmental problems associated with rare earth mining and production.[1] Xiao also commented the rare earth industry was oversaturated and faced low resource utilitization, leading to systemic underpricing and an overabundance of “low-level rare earth products,” which in the long-run “is not helpful for innovation and technological progress” (State Council, March 1).

International Implications

China has proven willing to leverage its control over rare earths in international diplomacy in the past. In 2010, China temporarily cut off rare earth exports to Japan following a diplomatic spat over the contested Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands, which are claimed by Beijing but administered by Japan. In 2019 and 2020, China threatened to suspend rare earth exports to the U.S. in response to trade tensions and U.S. arms shipments to Taiwan, respectively (Caixin, May 30, 2019; Global Times, October 26, 2020).

As tensions with China have increased, countries such as the U.S., Australia and Japan have begun working on initiatives to create an alternate supply chain for rare earths. Last September, then-U.S. President Trump signed an executive order declaring a national emergency in the mining industry that aimed to reduce the country’s dependence on China. According to the order, the U.S. imports 80 percent of its rare earth elements directly from China, with portions of the remainder being indirectly sourced from China through other countries (Defense News, October 1, 2020). In late February, President Biden signed an executive order to review and strengthen the resiliency of America’s supply chains, including “critical minerals and other identified strategic materials, including rare earths” (White House, February 24). As part of ongoing efforts to “decouple” the U.S.’s rare earth supply from China, the U.S. Department of Defense has given funding to the Australian Lynas Corporation and the Texas-based Blue Line Corporation to begin work on a heavy rare earth separation facility last July and a light rare earth processing facility in February (Mining.com, July 27, 2020; Defense.gov (U.S.), February 1). The European Union has also sought to diversify its rare earths supply, funding investments valued at $12 billion into rare earth and other green energy-related projects in 2020 (Mining.com, March 10).

Conclusion

China’s prioritization of emerging technologies to boost its economic development was most recently highlighted with the passing of the 14th Five Year Plan (FYP) (2021-2025) at the annual session of the National People’s Congress (NPC) on March 11 (Xinhua, March 14). Many of these technologies are dependent on the use of rare earths. Analysts have also highlighted the possible vulnerabilities of lithium and cobalt (critical for the production of energy-efficient batteries used in green technologies and consumer electronics) supply chains as well (SupChina, January 19). Press releases and readouts from the NPC emphasized China’s need for “self-reliance and self-strength” (自立自强, zili ziqiang), and Minister Xiao mentioned in passing that China had begun “mapping key industrial chains to identify our gaps and also our weaknesses and shortcomings,” echoing Biden’s similar prescription to review supply chains in the U.S. (State Council, March 1).

The Chinese state has shown itself to be chiefly concerned with its ability to meet domestic demand for renewable and defense technology needs—and a bit defensive in the face of repeated Western concerns about the threat of Chinese rare earth export controls. In response to media reports that the U.S., Australia, India and Japan discussed securing the rare earths supply chain at a recent Quad meeting, the Chinese tabloid Global Times wrote, “China has no intention to use rare earths as a countermeasure against any country, which would only accelerate development of rare earths in other markets” (Global Times, March 12). With an eye towards securing sustainable growth and development in the long term, the Chinese government has recently cracked down on mining sector excesses that have hurt output. While it is likely that the importance of rare earths will continue to loom large in China’s strategic and trade relationships with the rest of the world, the continuing reform of its domestic rare earths mining and production capabilities should also not be overlooked.

Elizabeth Chen is the editor of China Brief. For any comments, queries, or submissions, feel free to reach out to her at: cbeditor@jamestown.org.

Notes

[1] For more discussion on the toxic environmental impact of China’s rare earths production and refining, see: Michael Standaert, “China Wrestles with the Toxic Aftermath of Rare Earth Mining,” Yale Environment 360, July 2, 2019, https://e360.yale.edu/features/china-wrestles-with-the-toxic-aftermath-of-rare-earth-mining