China’s Port Investments in Sri Lanka Reflect Competition with India in the Indian Ocean

Publication: China Brief Volume: 21 Issue: 9

By:

Introduction

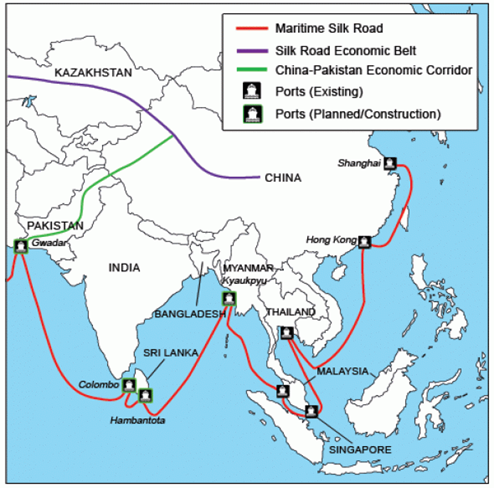

Located at the crossroads of global shipping lanes, Sri Lanka has become a significant recipient of Chinese economic and military influence in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR). For its part, Sri Lanka has largely welcomed China as a major investor and strategic partner in the past decade. China surpassed India to become Sri Lanka’s largest source of foreign direct investment (FDI) in 2011 (Gateway House, December 1, 2016). Additionally, China is Sri Lanka’s second largest source of trade imports and arms sales after India (SIPRI, accessed April 27; WITS, accessed April 27). In return, Sri Lanka has been a critical partner in China’s expansive foreign policy and infrastructure-focused Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), although the relationship has been balanced by local tensions over Chinese influence. Sri Lanka has been held up as an example of China’s so-called “debt trap diplomacy” model for foreign investment, but this narrative is insufficient to fully describe the complex situation unfolding, as well as obscuring the Sri Lankan government’s own agency in balancing neighboring powers while simultaneously seeking investments for ambitious development goals (China Brief, January 5, 2019, April 13, 2020).

Developments in Colombo

Recent news about the development of Sri Lanka’s strategically important port in the capital city of Colombo further highlights Sri Lanka’s delicate balancing act between China and India. In 2011, a consortium led by the state-owned enterprise (SOE) China Merchants Port Holdings Company signed a 35-year build, operate and transfer agreement to develop the deep water South Container Terminal, later called the Colombo International Container Terminal (CICT),at Colombo Port (Sri Lanka Foreign Ministry, accessed April 20). It promised an initial investment of $500 million in exchange for an 85 percent stake in CICT, which is now the only state of the art deep water terminal in South Asia. China Harbor Engineering Company (CHEC)—a key competitor with China Merchants, responsible for building the controversial Hambantota port project and which has also been involved in land reclamation efforts around Colombo—signed an agreement late last year to develop a financial district in Colombo Port City (Xinhua, December 18, 2020). China Harbor’s $1.4 billion investment marks the first of a $13 billion plan to develop Colombo Port City into a world-class financial and trade center (Xinhua, September 9, 2020). The agreement was promptly challenged by opposition parties, civil society groups, and labor unions alleging that the project violated Sri Lanka’s sovereignty, constitution, and labor rights (The Hindu, April 17).

Colombo Port is particularly significant for India, as it handles roughly 40 percent of transshipped container cargo bound for the Indian market. Even as the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi has sought to promote domestic transshipment hubs, it has also been determined to protect its dependence on Colombo port (Hindu Business Line, March 17). India, Japan and Sri Lanka signed a deal in 2019 for the Indian-based Adani Ports Group to lead the development of Colombo’s long-anticipated East Container Terminal (ECT), although this was quickly stalled by labor protests and then parliamentary elections in August 2020 (Livemint, November 3, 2020). According to one foreign analysis, “for the ‘Quad’ to be meaningful, India or Japan will have to have a place in Colombo port,” referring to the U.S.-India-Japan-Australia security framework that has been developed to counter China in the Indo-Pacific (Hellenic Shipping News, December 30, 2020).

But the India-Japan-Sri Lanka deal fell through in February, with the Sri Lankan government putting the blame on Adani after stakeholder negotiations failed (Hindu Business Line, March 2). Indian media reports, which frequently raise fears of outsized Chinese control over Sri Lanka, promptly claimed that this reneging was in fact due to Chinese influence.(Hindu Business Line, February 5;Indian Express, February 4). In March, Adani Ports and its subsidiary Special Economic Zones Limited (APSEZ) received a Letter of Intent to develop Colombo’s West Container Port, pending cabinet approval, based on similar arrangement to China Holding’s agreement to run the CICT (Adani, March 15). Some news reports saw this as a sop to Adani following the failure of the ECT negotiations (The Print, February 7).

Developing the ports in Colombo and Hambantota have remained key priorities for China’s top leadership, as both are heavily linked to the Xi-driven BRI. In an early 2021 call with his counterpart, Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi called for Sri Lanka and China to cooperate in developing both ports into “twin engines” of industrial development and economic growth and to stand together to “safeguard the legitimate rights and interests of developing countries” against the pressures of “some Western countries.” The Chinese readout of the call reported that Sri Lankan Foreign Minister Dinesh Gunawardena “said that Sri Lanka regards China as its closest friend and sincerely thanks China for its long-term, selfless help for Sri Lanka’s economic development, improvement of people’s livelihood, and coping with internal and external challenges” (PRC Foreign Ministry, February 24).This notably followed media reports that Colombo was reconsidering the Hambantota deal amid concerns that “the previous government made a mistake on the Hambantota port deal” (South China Morning Post, February 25).

Just over a month later, Chinese President Xi Jinping held a telephone conversation with the Sri Lankan President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, calling on the latter to “steadily push forward major projects like the Colombo Port City and the Hambantota Port, and promote high-quality collaboration in jointly building the Belt and Road.” Xi also noted that China and Sri Lanka had deepened their ties to help each other during the past year’s coronavirus pandemic, “writing a new chapter of China-Sri Lanka friendship” (Xinhua, March 30).

The Indian Ocean’s Strategic and Regional Importance

Access to the Indian Ocean’s sea routes is critical to Beijing, as today China is the world’s top oil importer, purchasing 542 million tons of crude oil in 2020 (General Administration of Customs, January 14). Last year, 53 percent of China’s crude oil imports came from the Middle East (SP Global, June 26, 2020), and passed through the Indian Ocean on its way to China, leading one Chinese strategist to conclude that China’s energy imports transit sea lanes controlled by other countries (CNKI, 2012). Unsurprisingly, maintaining friendly ports in the IOR is among China’s top economic and security interests. China has expanded its economic and military presence in the Indian Ocean over the last decade, with a 2015 Defense White Paper explicitly confirming the link between national security and development interests for the first time. It goes on to highlight the importance of China’s maritime interests, saying, “The traditional mentality that land outweighs sea must be abandoned, and great importance has to be attached to managing the seas and oceans and protecting maritime rights and interests” (Gov.cn, May 27, 2015).

In Sri Lanka, as in other states in the IOR, China has increased its influence through two main ways. First, it has built up trade and investment ties, developing ports in Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Myanmar. Second, it has expanded its naval presence. China’s naval strength and capabilities outclass India’s by most metrics, although India maintains a dominant position in the IOR, particularly near the Andaman Sea (Naval Technology, September 9, 2020).

From India’s perspective, about 90 percent of India’s trade by volume—and all of its vital oil imports—are carried by sea, so safe seaways are a strategic and economic imperative. Even the smallest signs of military cooperation between China and Sri Lanka are deeply worrying. Alarm bells went off in 2014 when Sri Lanka allowed two Chinese submarines to dock at Colombo port around the time of a state visit by Chinese President Xi Jinping (PRC Ministry of Defense, November 27, 2014; Economic Times, November 3, 2014). The Indian Navy has also raised concerns about the presence of Chinese research and survey vessels in Sri Lankan waters, which could be gathering data vital for the conduct of future naval operations, including submarine activity (The Print, November 14, 2020). Following Prime Minister Modi’s own visit to Sri Lanka in 2017, Sri Lanka has not given permission for Chinese submarines to dock at Colombo (South China Morning Post, May 12, 2017).

Increase in Sino-Sri Lankan Military and Economic Ties

China’s military ties with the Sri Lankan government have grown over the past 40 years, regardless of which political party holds power. Following the end of Sri Lanka civil war (1983-2009), during which India backed the Tamil secessionists, China began to gain limited military influence in Sri Lanka. This was demonstrated most recently by China’s gift of a frigate to the Sri Lanka navy following a visit by then-President Maithripala Sirisena to Beijing in May 2019, which reportedly also included the signing of security protocols and a $14 million deal for counter-insurgency surveillance technologies (South China Morning Post, July 8, 2019).

After the civil war, then-Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa explained the attractions of Chinese investment: “China helped us for the sake of development, that is all. Our war had shattered our country, we needed help to develop; they were ready, so why not?”(The Print, February 9, 2020). While affirming its commitment to a foreign policy that prioritizes “India first,” Sri Lanka has simultaneously maintained its right towards a so-called “policy of neutrality” with development as the top priority under the current president, Gotabaya Rajapaksa (brother of Mahinda Rajapaksa) (Colombo Page, September 30, 2020). Chinese investments in port capacity have enabled Sri Lanka to enhance its strategic position in the Indian Ocean and become a regional trading hub, with future plans to develop its ability to become a financial center as well (Hindu Business Line, December 16, 2014; Observer Research Foundation, July 22, 2019). However, it is important to note that Chinese investments in port facilities do not necessarily translate into military advantages (China Brief, April 13, 2020).

In addition to ports, China has invested in several other key economic sectors, including infrastructure, roads, and power, as well as dramatically ramping up its foreign aid and trade imports to Sri Lanka. By 2015, Chinese aid to Sri Lanka amounted to $12 billion, compared with $1.9 billion from India. Chinese FDI comprised 35 percent of Sri Lanka’s total FDI, compared to India’s 7 percent (Gateway House, December 1, 2016). In 2019,the value of cumulative Chinese infrastructure investment in Sri Lanka was equivalent to 14 percent of Sri Lanka’s GDP, surpassing India’s comparable $1.2 billion in investment (Chatham House, March 2020; Indian Ministry of External Affairs, September 2019). At the same time, Chinese imports to Sri Lanka have grown consistently since 2011, and in 2019 were roughly comparable with India’s (The Diplomat, August 1, 2019). In short, while Indian economic relations with Sri Lanka have either remained steady or weakened, trade, investment and foreign aid ties with China have grown rapidly in the last decade or so.

Last fall, President Rajapaksa once again denied that Chinese money created a “debt trap” subordinating Sri Lankan interests in the bilateral relationship, while also announcing that the two countries will move to restart free trade negotiations that have been on pause since 2017 (South China Morning Post, October 9, 2020). In October 2020, Rajapaksa asked Beijing for a $90 million aid grant, which was personally delivered by Chinese Communist Party Politburo Member Yang Jiechi. The Chinese embassy in Colombo lauded the “timely grant,” to be used for medical care, education and water supplies in Sri Lanka’s rural areas and “contribute to the well-being of [Sri Lankans] in a post-Covid era” (South China Morning Post, October 12, 2020).

Conclusion

Although Sri Lanka’s recent decision to grant the Adani Group the rights to develop Colombo port’s WCT reflects the government’s wish to balance between India and China, it is unlikely that the project signals a substantial increase in Indian investment in Sri Lanka. To put it bluntly, India even before the coronavirus pandemic was facing an economic slowdown that would have impacted its ability to prioritize foreign policy goals and make it “vulnerable to adventurism from adversaries” active in its traditional regional and maritime spheres of influence (Observer Research Foundation, December 6, 2019).

In contrast, China’s rising influence in the IOR stems from 40 years of sustained effort, buoyed by a top-down prioritization of its massive infrastructure-focused BRI. It has strengthened economic and military ties with Sri Lanka and other littoral and island states across the IOR. The effects of the recent pandemic mean that China’s economic and military presence in Sri Lanka—and concomitant presence in the Indian Ocean—are likely to increase.

Anita Inder Singh, a citizen of Sweden, is a Founding Professor of the Center for Peace and Conflict Resolution in New Delhi. Previously, she was a Fellow at the National Endowment for Democracy and has taught the international relations of Asia and Europe at the graduate and doctoral levels at Oxford and the London School of Economics and Political Science. Her articles have appeared in many publications, including The Guardian, The Far Eastern Economic Review, The Wall Street Journal Asia and Nikkei Asian Review. Her books include The United States, South Asia and the Global Anti-Terrorist Coalition (2006). She is currently writing a book on the United States and Asia. More of her work may be viewed at: www.anitaindersingh.com.