Greenland Likely to Be Cockpit of Arctic Conflict Between Russia and the West

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 18 Issue: 77

By:

On May 15, Russia will assume the rotating two-year chairmanship of the Arctic Council, a role President Vladimir Putin has already said Moscow will use to advance his country’s interests in the High North (see EDM, February 17, March 2, April 22). Initially, Russian moves are likely to involve both efforts to attract outside investment and other forms of support for Russia’s development of the Northern Sea Route (NSR) and to impel the United Nations to ratify Moscow’s expansive territorial water claims in the Arctic Ocean (Rossiyskaya Gazeta, May 5; Boris Morgunov, “The Prospects of Evolution of the Baseline Systems in the Arctic,” Water, April 14, 2021). But at the same time, there are indications Russia is also focusing in an unexpected direction—on Greenland—both defensively, to prevent any change in this island’s status in favor of the United States, and offensively, to seek to use it as a means to expand Russian influence still further.

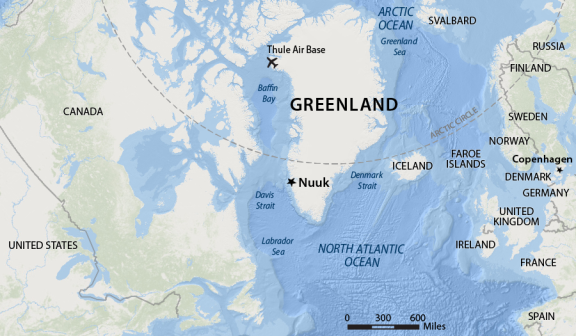

Russian analyst Sergei Sukhachev has recently suggested that Moscow is now directing new attention to a place that, as the title of John Griesemer’s 2002 dystopian novel suggests, “no one thinks about.” Moreover, according to Sukhachev, Moscow’s activities indicate that the Russian leadership may even have decided the Danish possession is now in play in the emerging international order (Profile, May 6). The Russian expert points out that even though Greenland is not as large as Mercator projections make it appear, it is still enormous and important: longer north to south than Moscow is from Jerusalem and east to west than St. Petersburg is from Copenhagen. But despite that, only 57,000 people live there, fewer than could fit in Moscow’s Luzhniki stadium and a figure that means the fate of this vast territory is likely to lie with major powers outside its borders.

The possibility that the world’s largest island really could be in play internationally was highlighted in August 2019, when then–United States President Donald Trump said he would like to “buy Greenland” from Denmark, a proposal that the Danish government promptly and unequivocally rejected (The Local, August 16, 2019). But that is hardly the end of this story, Sukhachev contends, given that “in fact, America has never been against acquiring territory” and that “as far as Greenland is concerned, the Americans even consider that they have certain rights to it” (Profile, May 6).

“On their side,” the Russian analyst acknowledges, lies geography. Greenland is clearly far more part of North America than of Europe. Second, there is exploration: Americans were among the first explorers of that island. And third, there is history. When the US purchased Alaska in 1867, it also sought to purchase Greenland. Sukhachev adds that the US pressed the issue for 50 years, but in April 1921, Denmark declared its complete sovereignty over Greenland, a move Washington did not dispute despite making plans to use Greenland if, as happened during World War II, Copenhagen lost control of its own government. And then, during the Cold War, the US incorporated Greenland into its defense structures and opened an airbase there, which remains to this day.

All this and much else, Sukharev writes, indicates that Trump was hardly an outlier on this issue. Washington has long been interested in Greenland and not just for security reasons. The island has immense mineral wealth: not only enormous reserves of uranium but also numerous rare earths, which are increasingly important for the high-technology economy. After Denmark granted Greenland autonomy in 1979, local people working with various foreign corporations began to develop these reserves despite opposition from some local people who feared that the mines would compromise the environment and their way of life.

The fight between those who want development and those who do not has deeply split Greenlanders, and an election, completed earlier this month, has left the island without a government based on any party with a majority of seats in the parliament. The experience of a vote there in 2018 suggests that this may well offer outsiders a chance to meddle—either to promote the independence of Greenland or their own dominance of this expansive Arctic territory. That Moscow may be among them does not seem farfetched considering the precedent of that earlier vote. After pro-independence parties won the Greenlandic elections then, some Europeans saw the hand of Moscow behind the outcome; Russian analysts, while insisting that was “not the case,” nonetheless acknowledged that “Greenland’s independence really can be potentially profitable for us.” One of their number, Yevgeny Krutikov, even wrote that Russia now has a wholly different position than the Soviet Union did. For the Soviets, the preservation of the territorial status quo was “almost a fetish”; but now, Moscow has a different view, and one of the places where this may be manifest is in Greenland. This is particularly true if the local natural resource reserves become more important and geopolitical competition over them with the US intensifies (Vzglyad, April 26, 2018).

For the last three years, both of those factors have become more significant. Russia is eying the uranium and rare earths Greenland has and would certainly like to close the US base at Thule as well as end the security understandings between Copenhagen and Washington that give the West a special role on the island. And what better time for promoting such moves than when Greenland itself is having trouble forming a government and when Moscow, having assumed the chairmanship of the Arctic Council, hopes to bring home some kind of new victory for Vladimir Putin?