Russian Opposition in Exile Attempts to Influence Situation Back Home

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 20 Issue: 155

By:

Over the past weekend, the Telegram channel “Nezygar,” closely aligned with the Russian presidential administration, erupted with posts criticizing the liberal positions prevalent among Russian exiles. The channel’s authors and experts concurred that the so-called “non-systemic opposition,” currently residing abroad, lacks both a substantial following in Russia and genuine political representation and influence in the West (T.me/russia2, October 7).

The authors of these posts point out that those attempting to shape the situation inside Russia are primarily journalists and activists who lack political agency. Government-affiliated analysts emphasize that Russian dissidents abroad are “disconnected from the people,” and their opposition to the war significantly diminishes their ability to sway ordinary Russians, who have largely united behind the military (T.me/russia2, October 7).

Furthermore, the authors of “Nezygar” underscore that representatives of Russian opposition entities and media abroad are heavily reliant on Western funding and, in their view, are “reliant on foreign intelligence agencies.” Nonetheless, they are not particularly sought after in the West, given their inability to impact the situation within Russia. Paradoxically, their very existence hinders the consolidation of Western society against Russia (T.me/russia2, October 7).

It is evident that these allegations contain a substantial element of propaganda. However, it is impossible to ignore the genuine challenges faced by the Russian opposition when it comes to engaging with their potential audience within the country. Many of these issues are objective and unavoidable, but they are deftly exploited by the Kremlin.

First and foremost, dissidents in exile are frequently criticized for their fragmentation. In practice, the opposition, with some exceptions, has been relatively successful in forming coalitions and has already demonstrated its ability to negotiate on key issues among themselves (see EDM, May 9). The problem lies in the fact that the primary issues shared by the entire new wave of political emigration, such as ending the war with Ukraine and toppling the Putin regime (Change.org, April 30), are seen within Russia as a “negative agenda.”

Other common principles held by most opposition movements, such as the establishment of genuine federalism and parliamentarism in Russia (Meduza, October 31, 2022), are often disregarded by the Russian majority. Consequently, external observers may get the impression that the opposition lacks a constructive agenda and a vision for the future.

However, the specific vision of Russia’s future structure and individual political programs do differ among various opposition groups. This diversity is entirely natural for a democratic society, where disagreements should be resolved through compromise and fair elections. Nonetheless, these objective differences are actively exploited by propaganda to suggest that the Russian opposition lacks a shared positive political agenda (RIA Novosti, February 21, 2021).

There are also disparities within the opposition regarding the methods of achieving even shared goals. For instance, some of the opposition’s representatives believe that regime change at this stage can only be accomplished through the use of force or the threat thereof (Forum Daily, May 5). Others firmly oppose armed struggle (Тwitter.com/Lev_Ponomarev, June 3). This division, combined with occasional competition among different political groups in the public sphere, further exacerbates the impression of disunity within the opposition (Meduza, October 2).

In addition, it is objectively difficult for opposition journalists based abroad to convey their viewpoints to the Russian audience. At a forum of anti-war initiatives called Russie Libertés held in Paris at the end of September, Dmitry Kolezev, the chief editor of the Republic publication, noted that information blockades, coupled with a lack of funding, severely restrict the possibilities of opposition journalism. This is especially significant given that the majority of people are not inclined to make efforts to access restricted content (Youtube, October 4).

Participants in the meeting also highlighted certain challenges in finding common ground with the Russian audience. For instance, the thesis that Ukraine must win the war can be met with disapproval from the Russian domestic audience. Forum participants emphasized the importance of gradually engaging with the Russian viewers, speaking to them in their language and offering more acceptable ideas. According to Dmitry Kolezev, one such idea could be the return of the mobilized from the front (Youtube, October 4).

Furthermore, in practice, Russian journalists in exile have limited resources for carefully tailored interaction with their Russian viewers, as “ambiguous” formulations can provoke negative reactions in the host countries. For example, one of the factors that led to the revocation of the license of the Russian opposition channel “Dozhd” in Latvia was a comment made by one of the hosts regarding the Russian army. Specifically, he referred to it as “our” army and expressed hope that after the “Dozhd” report, the number of violations of mobilized individuals’ rights would decrease (Svoboda.org, December 6, 2022).

Because of this, a complex dependency is created. Russian opposition journalists in exile are dependent on their host countries—not in terms of being influenced by their intelligence services, as Russian propaganda seeks to portray, but in practical terms. People need visas and residence permits, which has become increasingly challenging to obtain amid the introduction of new restrictions on Russian citizens (BBC–Russian Service, July 18).

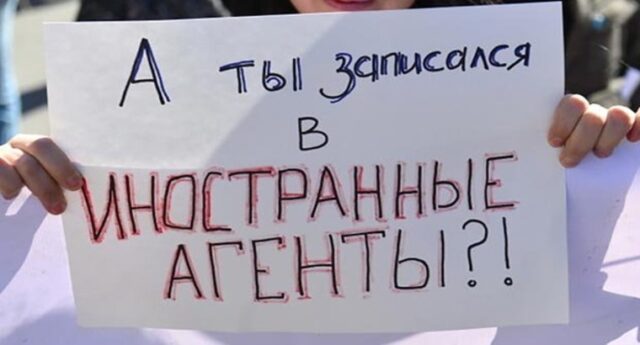

These difficulties intersect with the natural need to assimilate into a new society, leading to internal identity conflicts. In turn, the Russian audience keenly feels this conflict, which is further exacerbated by the stigmatization of almost all departing activists as “foreign agents.” As sociological surveys show, against the backdrop of the “patriotic consolidation” of society, the number of people perceiving these “foreign agents” as a channel of “negative Western influence on Russia” is increasing (Levada.ru, January 16).

It has become evident that the task of the basic survival of emigrants and attempts to prove their anti-war views in the West are increasingly conflicting with the goal of systematically influencing Russian society. Of course, this does not mean that one must play along with the Kremlin propaganda to achieve the latter goal. However, it is important to develop a deliberate and not overly radical interaction strategy with the Russian audience, understanding its fundamental fears and triggers. If the West manages to create such a platform for Russian activists, it could significantly enhance the dissidents’ ability to influence the situation in their country.