One Partnership at a Time: Beijing Steadily Creates a New Type of International Relations

Publication: China Brief Volume: 24 Issue: 17

By:

Executive Summary:

- The People’s Republic of China (PRC) has established a framework of authority and values that fosters voluntary compliance from subordinate states, as exemplified by the Solomon Islands’ recent diplomatic alignment with Beijing, abandoning recognition of Taiwan in favor of the PRC.

- The PRC makes explicit demands of its international partners, such as endorsing national reunification and rejecting Taiwan’s sovereignty, to encourage alignment with its foreign policy goals.

- The PRC’s ideological formulations of the “community of common destiny,” “a new type of international relations,” and “true multilateralism” underpin its negotiations with other countries.

- Initiatives like One Belt One Road (OBOR), the Global Development Initiative (GDI), the Global Security Initiative (GSI), and the Global Civilization Initiative (GCI) mark a new phase in the PRC’s engagement with the international system. The GSI and GCI currently exist as rhetorical formulations, while OBOR and the GDI have been actively implemented.

On September 4–6, Beijing hosted the 2024 Summit of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), which was attended by a record number of foreign leaders (MFA, August 23). In President Xi Jinping’s keynote address at the opening ceremony, he proposed ten partnership actions that would elevate the overall relations between the PRC and all African countries (with the exception of the Kingdom of Eswatini) to an “all-weather China-Africa community with a shared future for the new era” (Xinhua, September 5). The ten partnerships are underpinned by the PRC’s key initiatives—One Belt One Road (OBOR), the Global Development Initiative (GDI), the Global Security Initiative (GSI), and the Global Civilization Initiative (GCI)—with a marked emphasis on modernization and the elevation of strategic relations. Xi pledged 360 billion Renminbi ($50.7 billion) of financial support over the next three years, distributed to implement the ten recommended partnership actions (Xinhua, September 5).

This year’s FOCAC Summit is the latest instance of the PRC using a mixture of bilateral and multilateral fora to push its foreign policy concepts. In recent years, the PRC has accelerated efforts to ensure other countries share its preferences. Enforcing the “one-China principle,” under which Taiwan is seen as an inalienable part of the PRC, has long served as an important part of the country’s diplomatic strategy. Now, Beijing has begun to demand that its partners provide explicit endorsement of national reunification and the rejection of Taiwan’s sovereignty in order to reap the rewards of closer partnership (Nikkei Asia, June 24). Some countries, such as the Solomon Islands, have faced particular pressure in this regard. Earlier this summer, one of Islands’ members of parliament, Peter Kenilorea Jr., faced public criticism from his own government for his participation in the Inter-Parliamentary Alliance on China (IPAC) summit in Taipei (Solomon Star, August 3). PRC diplomats pressured politicians from at least six other countries not to attend (AP News, July 28).

Hungary Achieves Highest Level in PRC Diplomatic Hierarchy, Affirms ‘One-China’ Principle

Several key phrases recur in the PRC’s foreign policy pronouncements, statements, and agreements with other states. What Beijing refers to as a “new type of international relations (新型国际关系)” is the practice of what it calls “true multilateralism (真正的多边主义),” where countries build a “community of common destiny for humankind (人类命运共同体为)” (CIIS, 2023). While the phrases appear lofty in nature, in reality they refer to constructing a new international order, molding the United Nations in Beijing’s image, and reducing the power of other states to censure or restrict its activities (China Brief, February 26, 2018).

In terms of bilateral relationships, the PRC does not seek traditional alliances, instead promoting a system of “partnerships.” The PRC’s notion of “partnership” originated following the end of the Cold War, forming its first “strategic partnership” with Brazil in 1993, followed by a “partnership of strategic coordination” with Russia in 1996 (Shine.cn, July 26; FMPRC, accessed July 30). According to a report by the China Institute for International Studies, there are five discernible levels in the PRC’s diplomatic hierarchy (CIIS, October 20, 2023):

- “All-weather” or “permanent” strategic partners (“全天候”“永久”的战略伙伴关系);

- “Comprehensive” or “global” or “all-round” strategic partners (“全面”“全球”“全方位”的战略伙伴关系);

- Strategic partners (一般性战略伙伴关系);

- “Comprehensive” or “all-round” partners (“全面”或“全方位”的伙伴关系); and

- Partners (一般性伙伴关系).

Several countries sit at the top level of this hierarchy, including Russia, Pakistan, Venezuela, and Belarus. As of May 2024, Hungary has also been promoted into this bracket, following a visit from Xi Jinping during his first European tour in five years (MFA, May 10). This built upon the “comprehensive strategic partnership” established in 2017 (Xinhua, May 10; see China Brief, May 23). The announcement was accompanied by the unveiling of several additional agreements, including advancing cooperation on OBOR and Hungary’s “Eastern Opening” policy (Xinhua, May 10; China-CEE, April 10). During the talks, Xi Jinping remarked that the two countries “have set a model for building a new type of international relations,” and emphasized that collaboration with Hungary will contribute to “positive efforts” to building a “community of common destiny” (Xinhua, May 10). In return, Hungary reaffirmed its commitment to the “one-China principle” and its opposition to “all forms of separatist activities” aimed at breaking the PRC’s unity (Xinhua, May 10).

The language in these bilateral agreements, though largely symbolic, provides valuable insights into how the PRC perceives its partners. Integrating principles and objectives into a unique partnership is crucial for shaping a world order aligned with Beijing’s preferences. Hungary is not the only country to have articulated its opposition to “separatist activities.” Recently, both Kazakhstan and Belarus made statements to this effect, with the former promising to support “all efforts made by the Chinese government to achieve national reunification” (People’s Daily, July 4; International Department, July 9).

OBOR and Global Initiatives as Vectors of Influence

Alongside promoting adherence to its ambitions for unification with Taiwan, the PRC has also unveiled three global initiatives in recent years to cast itself as an innovative and ambitious stakeholder in the international order. These proposals—the Global Civilization Initiative (GCI), Global Development Initiative (GDI), and Global Security Initiative (GSI)—aim to reshape international cooperation in accordance with the PRC’s principles (see China Brief, November 21, 2023, March 3, 2023). In Beijing’s terminology, the GCI emphasizes respect for cultural diversity, common human values, and promoting international exchanges, while the GDI focuses on people-centered development and practical cooperation in areas like poverty alleviation and climate change. PRC Foreign Minister Wang Yi has stated that over 100 countries have requested to participate in the GDI (FMPRC, September 21, 2022; for the list of participants, see UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, accessed August 16). The GSI, meanwhile, which seeks to build a security community through dialogue and partnerships, is also said to have garnered support from over 100 countries and regional organizations, being incorporated into more than 90 bilateral and multilateral documents (People’s Daily Online, July 29).

While the GSI, GCI, and GDI are still new, OBOR has been expanding its influence for over a decade. Described as a “vivid example” of building a global community of common destiny and a “global public good and cooperation platform provided by China to the world,” it has enlisted more than three-quarters of the world’s countries and 30 multilateral organizations (Embassy of the PRC in Italy, September 26, 2023). The GSI and GCI currently exist just as rhetorical formulations, while OBOR and the GDI have produced tangible results. The GDI has focused on targeted development efforts, such as the “Smiling Children” project in Nepal and the “Kit of Love” project in Cambodia (Xinhua, accessed August 14).

OBOR has already gone through several rounds of evolution since 2013. One key factor that differentiates it from other PRC initiatives is the bilateral character of its implementation. In contrast, the three global initiatives are framed in multilateral terms. OBOR is often conducted in ways that are recognizable as a form of checkbook diplomacy, using economic coercion to achieve diplomatic goals. For example, on March 26, 2023, Honduras switched its diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to the People’s Republic of China (PRC). A mere three months later, it joined OBOR. Taiwan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs argued that the PRC had used economic coercion to incentivize this flip (MOFA, March 26, 2023). Similarly, Panama (2017), the Dominican Republic (2018), El Salvador (2018), and Nicaragua (2022) all joined OBOR within a year of breaking diplomatic ties with Taipei. These countries also signed several memoranda of understanding (MOUs)—characteristically lacking transparency—on a variety of areas for cooperation, potentially allowing a high degree of PRC influence into their politics (The Prospect Foundation, April 8, 2022). Beijing has effectively combined hard economic power with non-material sources of national power to advance its diplomatic agenda in this way. Despite its claims of anti-hegemonism, Beijing’s approach to foreign policy is unusually coercive.

The PRC Extends Influence in the Solomon Islands

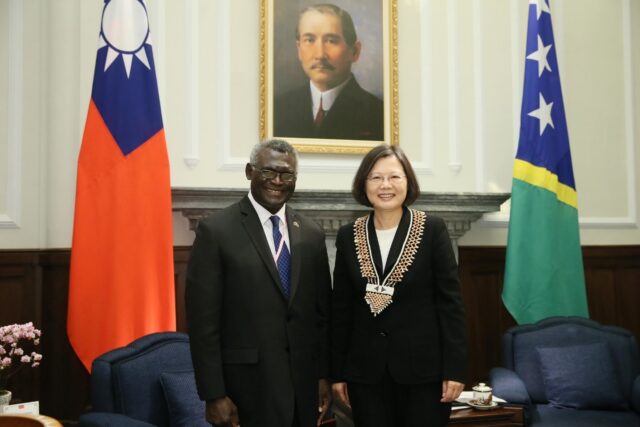

On July 12, in a one-on-one meeting in Beijing between PRC President Xi Jinping and Prime Minister Jeremiah Manele of the Solomon Islands, the latter reaffirmed his country’s commitment to the “one-China principle” and explicit support for Beijing’s efforts to achieve national reunification. Manele stated, “the Solomon Islands is ready to further deepen the comprehensive strategic partnership with China and build a community with a shared future between the two sides” (Xinhua, July 13). [2]

The Solomon Islands maintained diplomatic ties with Taiwan for 36 years, from May 23, 1983 to September 16, 2019. At that point, then-Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare—a proponent of pro-PRC policies—initiated a switch toward recognizing the PRC (MFA, September 16, 2019). This shift included a 2022 security pact which raised concerns among Western leaders about the potential establishment of a PRC military presence in the South Pacific (SCMP, March 20). A leaked copy of the security agreement appears to show that the Solomon Islands granted the PRC military privileges, such as ship visits and logistical support, leaving the door open to the possibility of a permanent military base, which would significantly extend the PRC’s strategic reach in the region (X.com/@Anne_MarieBrady, March 24, 2022; Saipan Tribune, May 16, 2022). In August 2022, Huawei and the China Harbor Engineering Company (CHEC; 中国港湾工程) were authorized by the Solomon Islands government to build 161 mobile broadband towers throughout the country. This was to be financed by a 20-year $65 million loan from the Export–Import Bank of China, a policy bank under the State Council, at a 1 percent interest rate (Global Times, August 19, 2022).

Diplomatic rapprochement with the PRC has not been universally accepted on the islands, however. Malaita, the Solomon Islands’ most populous province, has shown resistance to PRC influence and its activities in the country. Following the diplomatic switch, former Malaita Premier Daniel Suidani publicly rejected PRC aid in his 2019 “Auki Communiqué.” Ahead of provincial elections held in April this year, Suidani claimed that “many of us have received phone calls from [the opposing camp] telling them if they join the camp they will be given projects for their wards and also they will be receiving SI$300,000 [$35,000] each member—it’s getting to the next level” (The Sunday Guardian, May 5; X.com/@CleoPaskal, November 28, 2021; MPGIS, 2017).

The PRC also acted as the primary source of funding for the construction of the Pacific Games stadium in the Solomon Islands’ capital, Honiara. While Sogavare declared the diplomatic switch a developmental miracle, the World Bank has struck a more cautious note. In a report, the organization noted that the country had “a moderate level of debt” that “is consistently increasing amid persistent fiscal deficits driven by spending associated with the COVID-19 response and the Pacific Games 2023” (RNZ, May 8; World Bank, March 7). The Solomon Islands’ exposure to diplomatic and economic pressure from the PRC has led to public discontent and unrest. Paradoxically, this serves the PRC’s interests by providing it with greater leverage to weave itself further in the country’s social, political, and economic fabric (Reuters, November 29, 2021). This can be characterized as a form of “entropic warfare,” whereby unrest leads to a retrenchment of PRC interference and dependence, justified in the name of “stability” (The Sunday Guardian, June 4, 2022).

Conclusion

The PRC’s evolving foreign policy and diplomatic strategies reveal a sophisticated and multifaceted approach to global influence. Since its establishment in 1949, the PRC has consistently championed principles of peaceful coexistence and non-interference in its rhetoric. But its recent shift toward more assertive diplomacy underscores a broader ambition to reshape international relations. Through One Belt One Road and the three global initiatives (the GDI, GSI, and GCI), the PRC is not only expanding its economic and strategic footprint but also embedding its ideological framework into global diplomacy.

The strategic shift in countries such as the Solomon Islands highlights the effectiveness of the PRC’s checkbook diplomacy, where economic incentives and strategic partnerships are leveraged to secure political support and reshape regional dynamics. This approach not only advances the PRC’s geopolitical goals but also reinforces its position as a dominant force in international affairs. As the PRC continues to assert its vision of a “community of common destiny,” the implications of its diplomatic maneuvers will continue to resonate across the globe, challenging existing power structures and impacting the international order for years to come.

Notes

[1] The Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence (mutual respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity, mutual non-aggression, non- interference in each other’s internal affairs, equality and mutual benefit, and peaceful coexistence) are PRC foreign policy principles first put forward by then-PRC Premier Zhou Enlai on December 31, 1953, during a meeting with a delegation from the Indian government. At the 1955 Bandung Conference, the Five Principles were included in the Ten Principles for conducting international relations that Indonesia adopted; and in 1970 they were included in the Declaration on Principles of International Law concerning Friendly Relations and Co-Operation Among States in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations. They are characterized as fundamental principles behind PRC foreign policy (see Embassy of the PRC in the Islamic Republic of Iran, June 29, 2014). The links Xi mentions were also echoed at a recent event in Beijing commemorating the 70th anniversary of the Principles (PLA Daily, July 8).

[2] The “community of shared future” is Beijing’s updated, preferred English translation for “community of common destiny.” Outside of direct quotation, China Brief prefers to stick with the latter, which was the original official translation, and more closely reflects the Chinese term.