BERLIN CONSULTATIONS ON ABKHAZIA DERAILED

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 5 Issue: 147

By:

Moscow and Sukhumi have thwarted the proposed consultations in Berlin that could have launched a negotiating process toward resolution of the conflict in Abkhazia. The German government had offered to host the consultations on July 30-31, acting informally as mediator between Tbilisi and Sukhumi. The government of Georgia eagerly agreed. The event, however, has been blocked indefinitely, at the insistence of the Russian-backed Abkhaz authorities.

The meeting itself and the potential follow-up process could have capitalized on the recent political momentum, generated by German Minister of Foreign Affairs Frank-Walter Steinmeier’s outline of a plan to resolve the conflict in Abkhazia in stages (see EDM, July 22). Although the plan itself awaits some reworking and further development, the availability of a work-in-progress document from an influential and unbiased Western actor may help steer the process away from the Russian-controlled formats. This is why Moscow encouraged Sukhumi to thwart the German-proposed consultations, without Moscow incurring visible responsibility for the obstruction.

The consultations in Berlin were to have centered on face-to-face talks between representatives of the Georgian government and of Abkhaz authorities. The Georgians were seeking direct talks with the Abkhaz, in any format (other than the old, Russian-created one), hoping to launch direct talks in Berlin and continue them as a follow-up process.

Welcoming the German mediation for face-to-face talks, Tbilisi agreed to participate alongside the Abkhaz in a follow-up meeting in Berlin the next day in the framework of the UN Secretary General’s Group of Friends on Georgia, which consists of Russia, the United States, Britain, France, and Germany as the group’s current coordinator. Such a follow-up meeting would have signified the Group of Friends’ endorsement of the Georgian-Abkhaz face-to-face talks, laying a basis for continuation of those face-to-face talks (Civil Georgia, The Messenger, Kavkasia-Press, July 25-31).

Russia evidently decided to block such a development by orchestrating an Abkhaz refusal. Whether the incumbent Abkhaz leaders are at all able and willing to act on their own remains an unresolved question. In the event, Abkhaz leaders set conditions that were impossible to fulfill during intensive, at times frantic talks with German and U.S. diplomats in the run-up to the proposed date for the consultations.

“President” Sergei Bagapsh and “foreign minister” Sergei Shamba ruled out direct talks with Tbilisi, arguing that such talks or any novel format would be an unacceptable attempt to change the “existing format” (a cast-in-stone Russian argument). The Abkhaz leaders agreed in principle to participate in the Berlin consultations, but only within the Group of Friends (i.e., with Russia watching them), and separately from Georgia. The Abkhaz wanted two parallel meetings to be held in Berlin: by the Group of Friends with the Abkhaz and by the Group of Friends with Georgia. Such a format would have placed Georgia and the de facto Abkhaz authorities on a co-equal footing at the international level and nullified Georgia’s goal to start direct talks—a goal supported fully by the United States and Germany and in varying degrees by other Western diplomats.

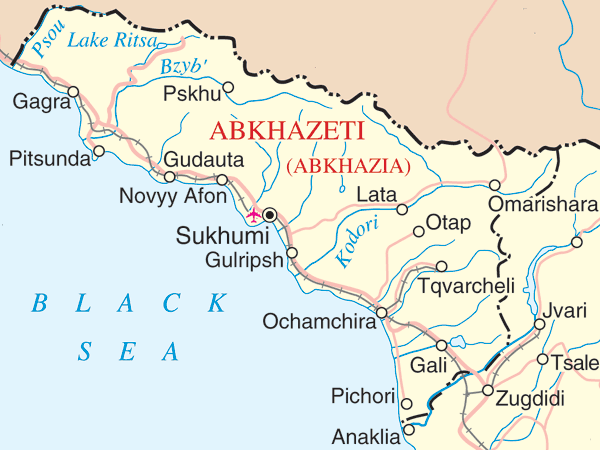

The Abkhaz leaders, furthermore, wanted the Berlin consultations to focus on meeting the two Abkhaz demands that form pre-conditions to any negotiation. Those twin demands are Georgian withdrawal from the upper Kodori gorge and the signing of a Georgian-Abkhaz agreement on non-use of force. But even if those pre-conditions are met, Sukhumi insists that it would only negotiate about recognition of Abkhazia’s secession from Georgia and legalization of its relations with Georgia on an inter-state basis. Abkhaz leaders insist that separation from Georgia is irreversible (Apsnypress, Interfax, Itar-Tass, July 25-31).

The Abkhaz leaders also claimed that they needed another month to study a document prepared for the Berlin consultations (a three-page document, according to some accounts). The dispute about rescheduling the Berlin event is, however, an irrelevant dispute, given Sukhumi’s intransigence regarding the proposed consultations’ format, topics, and basic goals.

Russia supports the two Abkhaz pre-conditions to negotiations. Indeed, Georgian withdrawal from upper Kodori and the signing of a non-use of force agreement are Moscow’s own demands on Tbilisi and pre-conditions to negotiations. Unlike Sukhumi, however, Moscow does not rule out negotiations about Abkhazia’s political status. Such negotiations could potentially cover a range of options, including far-reaching Abkhaz autonomy within Georgia.

By the same token Moscow is content to let the Abkhaz authorities look intransigent, seemingly exonerating Russia of its responsibility as sponsor of Abkhazia’s secession. The Steinmeier plan runs the risk of being blocked in the same way as Moscow and Sukhumi blocked discussion of German diplomat Dieter Boden’s concept paper for negotiations in 2000-2005 (the Boden Paper). During all those years the Abkhaz simply refused to take delivery of the document, so as to show that they were ruling out any political status short of full separation from Georgia.

At present, Abkhaz leaders have taken delivery of the Steinmeier document because they do not deem it incompatible with their stated goal of irreversible separation from Georgia. This declared goal may be genuine, may be foisted on them by Moscow behind the scene, or may be an opening gambit in a potential negotiating process. Direct, face-to-face talks with Tbilisi, without Moscow “holding a gun to them,” may enable the Abkhaz authorities to speak more constructively. This is why Moscow will do its best to block such direct talks, and even saddle the Abkhaz with the responsibility for a Moscow-orchestrated impasse.