Brief: Benin Becomes Bulwark Against Terrorism in West Africa

Publication: Terrorism Monitor Volume: 21 Issue: 15

By:

Benin’s location in coastal West Africa and role as an intermediary stop for travelers transiting from Mali into Nigeria make it an important geopolitical bulwark for halting the expansion of terrorist groups between Nigeria and the Sahel. It would appear that Benin is now taking threats of terrorism seriously, claiming to have detained 700 suspects, most of whom are from Benin, Nigeria, Niger, and Burkina Faso (northafricapost.com, May 23). The country has also, in some cases, been overly weary of potential terrorists recruiting on its territory, such as when it arrested and then deported the Belgian Jean-Louis Denis in January. He had once been imprisoned in Belgium for recruiting for Islamic State (IS), but had in this case ostensibly traveled to Benin on behalf of an Islamic humanitarian organization (sudinfo.be, February 5).

Benin itself has been targeted by jihadists since the first attack in the country was carried out in the nation’s north by al-Qaeda-affiliated Group for Supporters of Islam and Muslims (JNIM) (lanouvelletribune.info, February 12, 2021). It became apparent that terrorism might be becoming a more important issue locally after May 2019, when two French tourists were kidnapped and their tour guide was killed in a national park in northern Benin. The hostages were, however, freed by the bandits, who were loosely affiliated to JNIM or Islamic State in Greater Sahara (ISGS) (france24.com, May 5, 2019). Meanwhile, if these two cases were not of enough concern to Benin, in June 2022, JNIM also claimed its first attack in neighboring Togo, which demonstrated the broader expansion of JNIM and ISGS towards coastal West Africa (republicoftogo.com, June 4, 2022).

Moreover, reports of JNIM crossing paths with Ansaru, al-Qaeda’s affiliate in Nigeria, in Benin have created a sense of urgency for Benin—and the region more broadly—to pay more attention to Beninese counter-terrorism efforts (see Terrorism Monitor, December 16, 2021). Ansaru’s first ever kidnapping of a British and Italian engineer was also in Kebbi State, Nigeria, which is just across the border from Benin. This indicates that Ansaru was (and likely continues to be) familiar with and capable of operating from Benin. As recently as 2022, the Nigerian security services had warned of potential terrorist attacks in Kebbi, particularly of prison breaks (premiumtimesng.com, July 25, 2022). The fact that Hausa is the lingua franca in northern Nigeria as well as in some neighboring parts of northern Benin helps facilitate cross-border operations by Nigerian bandits and jihadists like Ansaru.

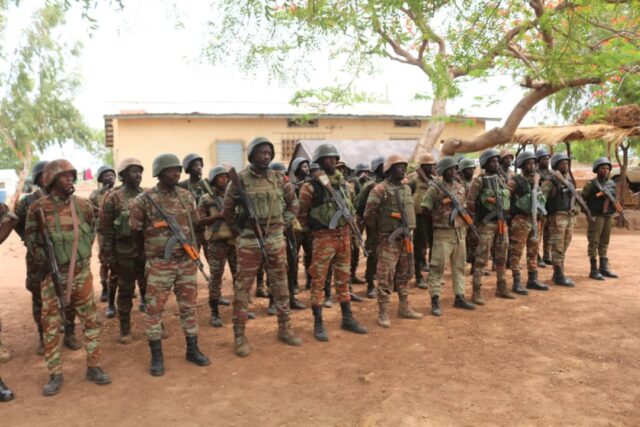

Despite its relatively small territory and population of 13 million, Benin’s military is able to concentrate on the JNIM and ISGS threat in part because its resources have not been diverted to other theaters, such as the Multinational Joint Task Force’s (MNJTF) battle against Boko Haram factions around Lake Chad. Benin is a member of the MNJTF along with the four Lake Chad basin countries—that is to say Nigeria, Niger, Chad, and Cameroon—and pledged 150 soldiers to the MNJTF in 2016 (saharareporters.com, March 15, 2016). Despite this, Beninese soldiers have not been fighting against Boko Haram, and the country’s contribution to the MNJTF has been largely symbolic. Had the MNTJF not been so bogged down combatting Boko Haram factions, the multilateral organization might have been able to support Benin along the Nigeria-Benin-Niger-Mali border axis. Alas, the MNJTF’s lack of funding is hampering its ability to conduct operations around Lake Chad, let alone increase its efforts along Benin’s borders (zagazola.org, July 6).