Briefs

Publication: Terrorism Monitor Volume: 21 Issue: 2

By:

JNIM Kidnappings Continue Across West Africa

With the world’s attention focused on issues like the insecurity arising from Russia’s war on Ukraine and the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan, al-Qaeda’s affiliate in West Africa, Group for Supporters of Islam and Muslims (JNIM), is quietly keeping up its parent group al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM)’s legacy for kidnapping foreigners. On January 5, South African Gerco van Deventer was reportedly taken to a JNIM camp in Mali (Twitter/@Mazhem_Alsaloum, January 5). He had originally been taken captive in Ubari (in the Fezzan region of Libya), where the El Sharara oil field is located (africaintelligence.com, July 11, 2022).

The fact that he was transferred to JNIM in Mali reveals not only JNIM’s cross-border networks, but also JNIM’s linkages with other trafficking and criminal groups. This is because JNIM is known to mostly have cells in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, but not Libya. It is, therefore, likely that JNIM made a deal with the Libyan smugglers who captured Gerco van Deventer. Van Deventer was kidnapped on the way to the airport in Ubari, where he was to fly back to South Africa after having been a paramedic at the oil facility on a one-month contract (Jacarandafm.com, May 7, 2019). According to his family, JNIM was demanding $1.5 million for his release in 2018 (dispatchlive.co.za, December 18, 2019).

Whether or not money is the primary factor determining Gerco van Deventer’s release remains a question. For example, in 2011 another South African, Stephen McGown, was abducted with co-travelers in Timbuktu. With the help of a humanitarian organization, negotiations commenced several years later and in 2017 he was released (Youtube/GiftoftheGiversFoundation, November 24, 2015). At that time, South Africa claimed that no ransom was paid to AQIM and JNIM for any of the hostages held in northern Mali, while Sweden refused to confirm or deny whether it had paid ransom for the release of a Swedish co-traveler of McGown a month earlier (aa.com.tr, August 3, 2017).

Currently, the most prominent case of a JNIM hostage remains that of a Frenchman, Olivier Dubois, who marked his 500th day in captivity this last August; public pressure prompted France to reaffirm their commitment to secure his release (france24.com, August 21, 2022). Dubois, who is a journalist with Libération and Jeune Afrique, was last seen publicly in a JNIM proof-of-life video in March 2022 (cpj.org, March 14, 2022). As the last remaining French hostage with a non-state actor internationally, JNIM holds psychological leverage over France, whose citizens are keenly aware of Dubois’ plight (quotidien-libre.fr, January 19).

Since May 2022, there were also five other Westerners, including three Italians, one Pole, and one American kidnapped in areas that JNIM operates within in the Sahel—as well as one Togolese citizen (alarabiya.com, November 23, 2022). The American, an 83-year old missionary from Louisiana, Sister Suellen Tennyson, was taken captive in Burkina Faso but released weeks later in Niger. The circumstances of Sister Tennyson’s release could not be disclosed due to a privacy agreement she signed with the FBI (wwltv.com, September 14, 2022).

Several years ago, AQIM videos were widely reported on in the Western press, as jihadism was more on the U.S. foreign policy radar at the time. Kidnappings in West Africa by JNIM, like that of Sister Tennyson, no longer generate the same publicity as they did previously. Nevertheless, as the continued taking of hostages in JNIM territories show, this tactic persists and remains a source of financial resources and psychological leverage for JNIM.

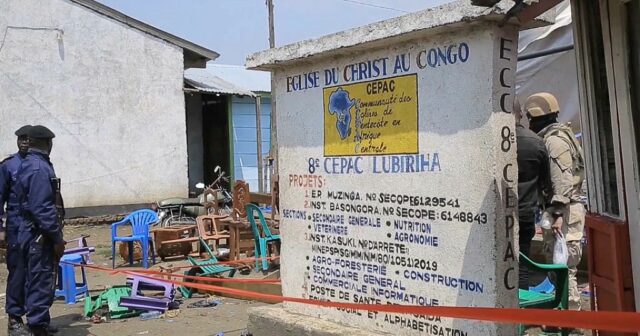

Congolese Christians Under Assault from Islamic State

On January 14, the Islamic State (IS)’s Congolese branch claimed an attack on a church in Kasindi, which killed 10 people and injured several dozen others (france24.com, January 14). What made this attack unique, however, was that it was reportedly a suicide bombing, although IS did not indicate that in its claim (Twitter/@AlexandruC4, January 18). Congolese authorities for their part claimed that the “suicide” bomber did not die during the detonation of the bomb but was actually injured and arrested under the rubble of the church after the bombing (acpcongo.com, January 17). The attack nevertheless continued a trend of IS fighters in the Congo targeting Christians in increasingly lethal operations.

One of the masterminds of the church attack was Abdirizak Muktar Garad, a Kenyan national from Wajir county (thestar.co.ke, January 17). The fact that the attacker came from a country outside of the Congo region evidences the expansion of the Congolese IS branch. Likewise, the IS branch in Mozambique has recruited along the Swahili Coast, including in Tanzania, Kenya, and the Comoros, and fielded a leader, Abu Yasir Hasan, from Tanzania itself (clubofmozambique.com, March 14, 2021). IS’s centralized leadership in the Middle East formally separated the Congolese and Mozambican branches in 2021 from what was a unified IS in Central African Province (ISCAP). Despite this, both branches still compete, or perhaps even collaborate, to recruit foreign fighters throughout the same geographic region of East Africa.

This prominent church attack followed several other less-reported Congolese branch attacks on Christians. For example, IS claimed the Congolese branch’s burning of down of Christians’ houses along the Beni-Butumbo road (Twitter/@Eldrudo, October 24). Only days before those burnings, on October 20, the Congolese branch also killed a Catholic nun and six other Christians in a similar area (aciafrica.com, October 21). This suggests the branch’s fighters near Beni, which like most Congolese towns is majority Christian, are increasingly and specifically targeting Christians.

On the strategic level, IS in the Congo benefits from attacking Christians in two ways. First, the attacks cause an uproar, which generates attention towards IS globally. This is why IS was quick to promote the church bombing in Kasindi after the operation. Second, IS is able to pillage from Christian villages that it attacks to replenish supplies of food and other essentials.

Another advantage for the Congolese branch is that government forces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) are increasingly distracted by their other counter-insurgency effort against the M23 rebels, who claim to represent Congolese Tutsis (aljazeera.com, January 18). One might expect that Rwanda would support Congolese forces against IS fighters in the Congo, especially because of Rwanda’s large-scale counter-terrorism operations in Mozambique and the fact that the Congolese branch has carried out attacks in Rwanda itself (Terrorism Monitor, October 21, 2021). Nevertheless, the tense relations between the DRC and Rwanda have limited Rwanda’s presence in the Congo. The latter’s officials as well as France, Germany, and other major powers, for example, suspect Rwandan leaders of aiding their fellow Tutsis to destabilize the DRC (africanews.com, December 21, 2022).

This lack of counter-terrorism coordination amid the destructive attacks on Christians indicates the war on the Congolese branch is far from over. In fact, the Congolese branch is, if anything, seeing a resurgence like their Mozambican and Sahelian cohorts are in their respective regions (Terrorism Monitor, January 6). IS, therefore, may be struggling in the Middle East, but its prospects in Africa remain favorable through its fighters in Congo, Mozambique, the Sahel, and Nigeria.