Security Risks Rise in Rohingya Refugee Camps on the Myanmar-Bangladeshi Border

Publication: Terrorism Monitor Volume: 21 Issue: 1

By:

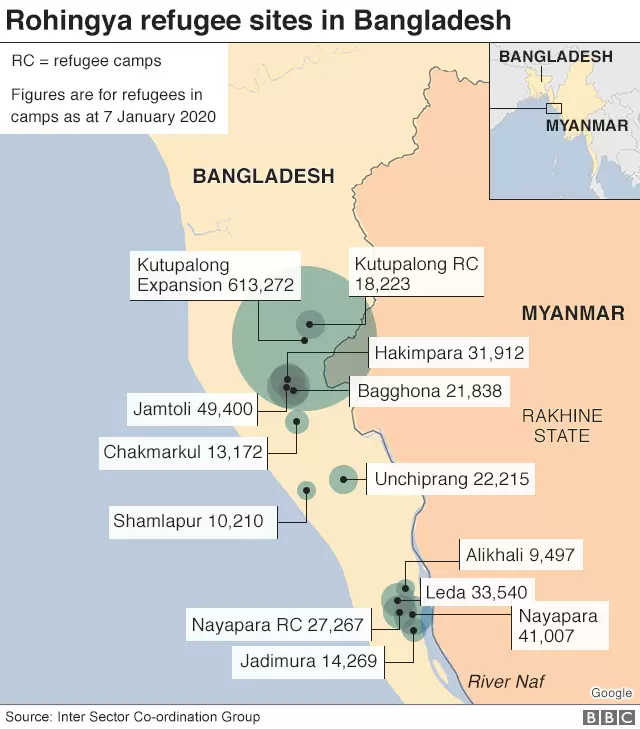

As Rohingya refugee camps near the Naf river (which partially separates Bangladesh and Myanmar) become hubs for organized crime and militants, Bangladeshi authorities fear spillover effects for Bangladesh and for the region more broadly. Refugee camps have mushroomed along Bangladesh’s southeastern border since August 2017 as a result of the Rohingya exodus from Myanmar’s Rakhine State. However, now these refugee camps are becoming havens for crime, replete with gang violence, targeted killings, and the trafficking of drugs, firearms, and counterfeit currency.

Security agencies in Bangladesh blame these activities on the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) and a relatively new armed militant group, Islami Mahaz (IM), along with several armed criminal factions. The problem can be seen in the over 35 camps located in Ukhiya and Teknaf of Bangladesh’s Cox’s Bazar district (Dhaka Tribune, October 26; BDNews.com, September 29). Bangladesh still officially denies the presence of Rohingya militants on its soil and maintains a zero tolerance policy towards terrorism, instead proudly touting its multifaceted preventive measures. However, the country is waking up to this novel security risk within its borders more clearly now than ever.

Crime in Cox’s Bazar

Bangladesh now hosts over one million Rohingyas in various camps on its territory. Five years have passed since Rakhine State in Myanmar witnessed a military crackdown on the country’s restive Rohingya Muslims. This led to a fresh exodus of refugees into bordering Bangladesh from August 2017 onwards. According to Bangladeshi police sources, between August 2017 and September 2022, there were nearly 2,500 cases of crime and violence, including 116 targeted killings, in the Rohingya camps. Seven identified terrorist gangs exist in Teknaf (including Hakim Bahini, Sadeq Bahini, and Hasan Bahini) and another seven gangs in Ukhiya (such as Munna Bahini, Asad Bahini and Rahim Bahini) (Dhaka Tribune, August 25; Prothom Alo, October 3, 2021).

Although Bangladeshi authorities have claimed that there has been a substantive reduction in violent incidents, in October and November 2022 there was a spike in violence. Militant factions affiliated with ARSA and IM began targeting local community and religious leaders. Also under threat are civilians who advocate for Rohingya rights and their safe repatriation to their native Rakhine State, as opposed to remaining in the camps in Cox’s Bazar (New Age, October 27). Further, besides targeting Myanmar’s army in cross-border attacks, Rohingya militant factions now often confront Bangladeshi security and intelligence personnel. The main groups of targeted personnel include the Directorate General of Forces Intelligence (DGFI), Border Guards Bangladesh (BGB), and the Armed Police Battalion (APBn), who are tasked with guarding the borders as well as the maintaining law and order in the camps. The motives of these militant groups seem to be to control the lucrative illicit trafficking and trade markets while silencing voices who oppose their role in criminal activities in the refugee camps or prefer to cooperate with the Bangladeshi police.

One of the most notable attacks was on November 29, when Rohingya militants killed Shahab Uddin, who was a junior camp leader in Ukhiya. Mohammad Jasim, a Rohingya leader, was also abducted and killed at Balukhali camp in Ukhiya on October 26. Earlier, between October 12 and 15, three community leaders identified as Mohammad Anwar, Mohammad Yunus, and Mohammad Hossain were killed in separate incidents (Dhaka Tribune, November 29; Daily Star, October 27; The Business Standard, October 15). On November 14, a Bangladeshi military intelligence officer, Rizwan Rushdee, was killed in a counter-narcotics operation near a Rohingya refugee camp in the Bandarban area. Bandarban is known as the “zero point” or “no-man’s land” between Myanmar and Bangladesh. Similar to Rizwan Rushdee’s death, ARSA was accused of killing Saidul Islam, a member of the Bangladeshi APBn on September 19 (New Age, November 26; New Age, November 4). These above-mentioned events are not isolated, but reveal a pattern in recent months of targeted violence not only against vocal Rohingya community leaders but also against security personnel. This spate of attacks prompted Bangladeshi authorities to launch a counter-terrorism effort in late October, termed “Operation Root Out.”

ARSA’s Other High-Profile Operations

ARSA’s direct involvement in the camps has been largely confirmed through eyewitness accounts or circumstantial evidence rather than, for example, ARSA’s own claims or visual evidence. A high-level investigation of ARSA’s commander-in-chief, Abu Ammar Jununi (also known as Attaullah), and 65 other members was launched after the spike in violence in refugee camps. Attaullah and his followers were accused of orchestrating assassinations of leaders of the Rohingya rights movement to hinder efforts of Rohingya repatriation to Myanmar. ARSA, which is locally known as “Al Yakin,” was also blamed for the murder of six teachers and students at an Islamic madrasa (seminary) controlled by the IM faction under the leadership of Maulvi Selim Ullah in October 2021 (BDNews.com, June 13).

In a media statement, ARSA even denied its involvement in killing Bangladeshi intelligence officer Rizwan Rushdee (Twitter/@ARSA_Official, December 3). The group further reiterated its goal to reinstate the legitimate rights of Rohingyas by fighting only with Myanmar’s Army and denied committing any atrocities against indigenous Rohingyas themselves (Twitter/@ARSA_Official, October 24, 2021). However convinced one is by ARSA’s claims through its own propaganda channels, Bangladeshi police have found evidence of ARSA militants’ involvement in Rushdee’s and Saidul Islam’s deaths.

The most high-profile assassination came in late September 2021, when suspected ARSA militants killed Mohammad Mohib Ullah, who was the chairman of the Arakan Rohingya Society for Peace and Human Rights (ARSPH). Mohib Ullah had gained international popularity for raising the issue of Rohingya rights at international forums, including attending meetings at the White House and the UN (Daily Observer, September 12). His call to commemorate Rohingya Genocide Day in August 2019 found traction with refugees, causing thousands to march to mark the occasion in Kutupalong camp in Ukhiya. His murder was reportedly aimed at blocking Rohingya repatriation efforts to Myanmar by ARSPH, which enjoyed the support of international agencies. As a leading advocate for the persecuted Rohingya Muslim minority, Mohib Ullah’s “Going Home” campaign vowed safe return of displaced Rohingyas to Myanmar, but ARSA made sure it never came to fruition (Prathom Alo, June 14).

Countering ARSA

ARSA initially portrayed itself as a jihadist movement seeking support from transnational jihadist groups and Islamic charities. However, it later rebranded as something between an ethno-nationalist movement and an armed resistance movement. ARSA also denied having any links with transnational terrorist organizations, such as al-Qaeda, Islamic State (IS) or Lashkar-e-Taiba, even though these groups have sought public support for the Rohingya cause (Twitter/ ARSA_Offcial, September 14, 2017). Bangladeshi police nevertheless found evidence of ARSA’s ties with al-Qaeda-linked Ansar al Islam (AaI) and other Islamist factions in Bangladesh, including Jamaat-ul-Mujahideen Bangladesh (JMB). In November, the elite Counterterrorism and Transnational Crime (CTTC) unit, for example, arrested Rafat Chowdhury, who is the lead coordinator of the banned AaI, in Sylhet. CTTC investigators believed Chowdhury had active ties with ARSA and other Rohingya factions (BDNews.com, November 10).

Since the death of Mohib Ullah, Bangladeshi security agencies have also carried out intermittent raids against ARSA and other factions and have cracked down on the firearms and drug trade—namely meth and yaba—in the refugee camps and on the border. Bangladeshi police did this by arresting several senior members of ARSA, including ARSA’s spiritual heads of the Ulema (Scholars), Maulvi Zakoria and Mohammad Shah Ali, the latter of whom is the brother of Attaullah (Daily Star, January 17). Another late October 2022 operation involved the security agencies intensifying their campaign against crime and terrorism and arresting more than 50 Rohingya militants and their supporters from various refugee camps (Business Recorder, October 30).

Nevertheless, as Myanmar’s relentless military offensive in the Rakhine State has continued, ARSA and other militant factions have lost territory. As a result, they have increasingly used the refugee camps as safe havens and recruiting grounds. Bangladeshi police have also seen ARSA and other militant factions subsequently engaged in turf wars, as well as extorting Rohingyas working with local and international aid agencies and traders and shopkeepers inside the camps.

Conclusion

During its formative years, ARSA was accused of intimidating and attacking Rohingya civilians for being suspected informants for Myanmar’s security forces or forcing them to join the insurgency against Myanmar’s forces. The group also targeted other minority populations, such as Hindus, for taking sides with the Buddhist majority in Myanmar. However, now the growing militant activities by ARSA and violent turf wars in the refugee camps pose law and order problems for Bangladesh and the refugee populations themselves. Rival militant factions, including ARSA, are fighting to control the illegal, yet lucrative, drug and arms trade at the borders of Myanmar and Bangladesh and inside the refugee camps. If the situation worsens, ARSA’s cross-border movement and penetration into the Bangladeshi hinterlands will exacerbate Bangladesh’s struggle to contain the instability on its southeastern frontier.