Central Asian Countries Erecting New Cities to Cope With Population Explosion

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 14 Issue: 26

By:

Even though fertility rates have fallen in Central Asia over the last two decades, the earlier rise in the number of births means that the populations of these countries continue to grow far more rapidly than anywhere else in the former Soviet space. Tajikistan is the leader, with its government estimating that the country is increasing by more than 2.2 percent every year (Stat.tj, accessed February 28). Such explosive growth means that the share of young people is far higher than elsewhere. Furthermore, these Central Asian countries are having a hard time providing jobs for all those reaching adulthood. As a result, population pressures on existing urbanized areas are especially great as people flow in from the even more impoverished villages, where birthrates remain higher than in the cities.

In most countries where population growth is either moderate or even negative, existing cities can readily absorb people migrating in from the countryside. But in Central Asia, the size of the influx from the villages is so great that two countries in the region—Tajikistan and Uzbekistan—have adopted the unusual strategy of creating entirely new cities. This is an incredibly expensive move given the infrastructure costs involved. And yet, both Dushanbe and Tashkent have apparently decided it is worthwhile to build new municipalities from scratch. Their reasons are two-fold: On the one hand, the existing cities in Tajikistan and Uzbekistan are facing both a collapse of communal services as well as an absence of jobs—two factors that could lead to social unrest. And on the other hand, it is often the case that young people moving to those cities link up with people from their home areas who have moved there earlier and are “re-traditionalized” rather than integrated—a trend that can sometimes lead to more Islamist radicalism (FerganaNews, February 20, 21).

Tajikistan and Uzbekistan have thus decided on a strategy pioneered by the People’s Republic of China. By building numerous new urban areas across the Chinse countryside, Beijing has largely been able to stem the rise of protest movements in that country’s major preexisting cities. But this has come at the cost of enormous investment in places that often remain “ghost towns,” where no companies and hence no people have been willing to move. China has sufficient resources to absorb these costs, but it is far from clear that either Tajikistan or Uzbekistan does. And hence, their experiment in social management may end not with integrating the burgeoning influx of people from the villages into national life but rather by those internal migrants’ radicalization and willingness to align themselves with radical Islamists against the incumbent regimes.

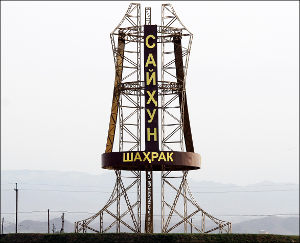

Two articles this past week on the FerganaNews portal provide a glimpse into what is taking place in these new places. Writing about Tajikistan, journalist Aziz Rustamov says that “despite the financial crisis,” Dushanbe has gone ahead with its plans to build four new cities: Saykhun in Bobodzhongarfur district, Bakhoriston in the Istaravshan district, Mokhpari in the Isfara district and Mekhrobod in Sogdian oblast. Plans for doing so were first announced in 2009; and in 2014–2015, officials signaled they were beginning work, creating infrastructure like roads, water pipelines and electrical grids (FerganaNews, February 21).

Dushanbe plans for each of these four new cities to become the home of some 250,000 to 300,000 people. It hopes that this will slow the movement from the villages to the country’s preexisting major cities and thus relieve them from the current pressures of overpopulation. Most of Tajikistan’s planned new cities are located some distance from existing regional centers. As of now, neither the housing, nor the infrastructure, nor the firms that are supposed to provide employment are fully in place. The government lacks the money to proceed as it had intended, and both Tajikistani villagers and Tajikistani businessmen are drawing the obvious conclusions, at least for the short term.

Unless the regime can overcome these problems and create tangible “conditions for people” rather than models from plans, Rustamov says, these cities may prove stillborn. Such an outcome would be yet another example of Soviet-style gigantism in which the authorities proclaim a bright future (however difficult the present) but are simply unable to deliver. This type of spectacular failure to follow through could encourage disheartened locals to listen to Islamist radicals from within their own country or from neighboring Afghanistan.

On the other hand, the situation in Uzbekistan with regard to such cities is better for at least three reasons, according to Sid Yanushev (FerganaNews, February 20): First, Tashkent has not announced such an ambitious program but instead is focusing on only one city, Nazarbek, into which it has been able to invest heavily. Second, Uzbekistan has far more money than does Tajikistan and so can spend it. And third—and this is likely the most important factor—Uzbekistan has built its new city close to the capital of Tashkent. This lessens the government’s upfront infrastructure costs. But in addition, it also makes residence in Nazarbek—a place of clean air and water and cheap homes (apartments equivalent to those in Tashkent cost only 50 percent as much)—a more attractive prospect than living in any of the four new cities being built in Tajikistan.

Of course, Nazarbek alone will not solve Uzbekistan’s surging population growth. (It too is around two percent a year.) In fact, this new “city” may soon be absorbed within the Tashkent agglomeration. And that means that the government will have to consider what to do next—proceed down the route being followed in Tajikistan or simply try to better manage the influx of villagers into the major cities, especially in the already overpopulated Ferghana Valley.