China and Iran Expand Relations After Sanctions’ End

Publication: China Brief Volume: 16 Issue: 5

By:

January 16 marked the highly anticipated implementation of the nuclear accord signed between Iran and the five permanent members of the UN Security Council plus Germany (P5+1) known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). The occasion was hailed by China as an important diplomatic breakthrough that will benefit Iran and the international community (Xinhua, January 17). The agreement paved the way for the removal of economic sanctions levied against Iran by the United States, European Union, and United Nations in exchange for Iran’s pledge to cease any attempt to develop nuclear weapons. While some U.S.-imposed sanctions will remain in place, most sanctions regulating trade with Iran will be lifted due to Iran’s acknowledged compliance with the accord. Widely touted as one of the world’s most attractive emerging markets, foreign investors previously deterred by sanctions are eager to stake their claim in the Islamic Republic. In this context, the circumstances surrounding Chinese President Xi Jinping’s January visit to Iran merit consideration.

Xi’s visit to Iran represented the third leg of a Middle East tour that saw visits to Saudi Arabia and Egypt. It also marked the first state-level visit by a Chinese premier to Iran in fourteen years and the first visit by a foreign leader to Iran after the lifting of economic sanctions (al-Jazeera [Doha], January 24; Xinhua, January 23; Press TV [Tehran], January 23; Middle East Eye, January 23). China’s evolving Middle East agenda remains a subject of scrutiny. As the world’s second-biggest importer of crude oil and the world’s largest aggregate consumer of energy overall, Chinese behavior toward the wider Middle East is often explained as a byproduct of its insatiable appetite for energy resources. China’s rise on the global stage has likewise been accompanied by a shift in its strategic calculus. China’s adoption of an increasingly proactive foreign policy toward the Middle East, which includes multifaceted relations with Iran, is frequently cited as a validation of its ascendancy. With a strong bilateral framework that has been cultivated through years of diplomacy and economic and defense contacts, it is no surprise that China is poised to reap the some of the greatest benefits of Iran’s return to the international fold.

Diplomacy

The enthusiastic tone of the political discourse in Tehran during Xi’s visit is illustrative of the high priority China and Iran attach to bilateral relations. Both countries publicly hailed Xi’s trip to the Islamic Republic in a statement issued jointly by Iranian President Hassan Rouhani and Xi. The Iranian leader praised the current state of Sino-Iranian relations and called Xi’s visit a “historic event” that signaled the start of a “new chapter” in the bilateral relationship whose origins go back millennia. Rouhani also thanked Xi for the role China played in helping forge the JCPOA. Iran lacks a history of conflict or hostility with China, allowing China to be a de facto advocate for Iran during the negotiations. Rouhani affirmed that both leaders had agreed on a framework to further advance the scope of Sino-Iranian relations to what was described as a “comprehensive strategic partnership” involving bilateral, regional, and international affairs. In this regard, China and Iran outlined a 25-year road map to foster greater cooperation in the political, economic, defense, security, culture, science, infrastructure, industry, and legal arenas (Press TV, January 23; Islamic Republic News Agency [Tehran], January 23).

Xi echoed his Iranian counterpart’s enthusiasm for the prospects of Sino-Iranian relations. In a manner that has come to epitomize Chinese diplomacy in the Middle East, Xi referenced the history of Chinese and Iranian contacts that helped advance the ancient Silk Road trade routes that fostered economic and cultural exchanges between Asia, Africa, and Europe. He added that both China and Iran are the successors of ancient civilizations that have enjoyed friendly relations based on the principles of mutual respect, shared interests, and other common values, a bond that has endured despite what he described as the “test of the vicissitudes of the international landscape.”

Xi also highlighted Iran’s role in China’s effort to revive the ancient Silk Road under the auspices of its Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road (usually referred to as One Belt, One Road) endeavor (Xinhua, January 24; Xinhua, January 23). China’s efforts to resurrect the ancient Silk Road trade routes that traverse Iran are already paying dividends. The first Chinese cargo container train arrived in Iran in early February after travelling approximately 6,500 miles over a fourteen-day period from its point of origin in the coastal Zhejiang Province and after passing through Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan (Diplomat [Tokyo]; Xinhua, February 14, February 16). The expansion of rail connections between China and Iran is a priority for Beijing. In 2015, the China Railway Corporation (CRC) presented a plan to link China and Iran via a high-speed railway through a proposed route that would originate in China’s western Xinjiang Province and pass through Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan before reaching Iran. China has a notable presence in Iran’s rail sector. In partnership with Iran’s MAPNA Group, the China National Machinery Import and Export Corporation (CMC) and Beijing Supower Technology Company helped finance and modernize a rail line linking Tehran to Mashhad with an investment of $2 billion. The China International Trust and Investment Corporation (CITIC) played a major role in the construction of Tehran’s subway system and ongoing efforts to modernize and expand its capacity (Shanghai Daily [Shanghai], February 17; China Central Television, January 19; Islamic Republic News Agency, December 17, 2015; Trade Arabia [Manama], June 22, 2015). China and Iran recently inaugurated a new maritime shipping route that links China’s Qinzhou Port to Iran’s Bandar Abbas Port (Financial Tribune [Tehran], February 3; World Maritime News, February 2). The number of direct flights between China and Iran has also increased to accommodate the anticipated influx of Chinese visitors to Iran (China Aviation Daily [Hefei], February 4).

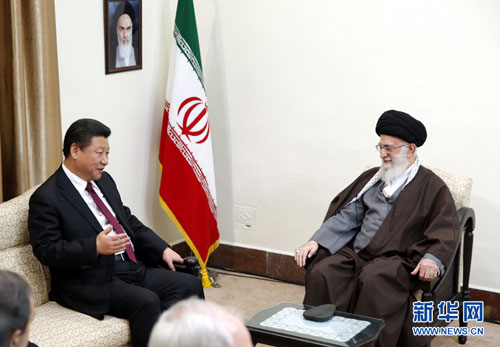

China and Iran concluded seventeen agreements in all outlining future plans to further cooperation in the areas of trade, banking and finance, economic development, industry, and scientific and environmental initiatives (Press TV, January 23). In an apparent admonition of the United States, Rouhani and Xi reiterated their support for a multipolar world order. Xi added that China respects the sovereignty of the peoples of the region and their right to pursue political and economic paradigms that are best suited to their respective histories and cultures. Xi also offered his support for upgrading Iran’s status as an observer to the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) to full membership (Xinhua, January 24; Islamic Republic News Agency, January 23; Fars News Agency [Tehran], January 23). Xi also met with Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. The Supreme Leader acknowledged the support China provided to Iran over the years and affirmed Iran’s commitment to continue to work to expand their level of mutual cooperation to new levels. Khamenei also opined that the “hostile polices” pursued by the United States have driven Iran to seek relations with other likeminded, “independent” countries (Xinhua, January 23; Press TV, January 23). The significance of Khamenei’s public endorsement of the latest developments in Sino-Iranian relations should not be understated. Despite the inherent complexity of a political sphere riven by numerous competing and overlapping ideological currents that transcend the reductionist binary of “moderate” versus “hardliner,” the Office of the Supreme Leader represents Iran’s most powerful source of authority on domestic and foreign policy. By all accounts, Iran’s engagement with China represents a consensus issue in Iranian politics that transcends political and ideological divides.

Trade and Energy

As Iran’s largest trade partner, negotiations surrounding the state of bilateral trade figured prominently during Xi’s visit to Iran. The volume of bilateral trade between Iran and China was estimated at around $50 billion in 2015. Both sides announced their goal of increasing bilateral trade to $600 billion over the next decade. As a key source of China’s oil imports—Iranian crude oil China represents between 9 and 12 percent of China’s oil imports— the trade balance between the two countries has favored Iran for the last thirty years. Led by the decline in oil and other commodity prices, the trade balance shifted in favor of China in 2013 when the trade volume dropped to around $39 billion before rebounding. Over one-third of Iran’s total exports are earmarked for China (Platts [London], January 25; al-Jazeera, January 24; Iranian Students News Agency [Tehran], January 5; China Briefing [Hong Kong], September 30, 2015; U.S Energy Information Administration, May 14, 2015). Iran has the world’s fourth largest reserves of crude oil, the world’s second-largest reserves of natural gas and is the world’s third-largest producer of natural gas. Even in an era of declining energy prices and a sluggish global economy, Iran is keen to attract foreign investment in its upstream and downstream oil and gas sectors, boost overall production, and recapture market share that eluded it during the sanctions era. China and other Asian markets led by Japan are central to Iran’s long-term energy export strategy. The China Petroleum and Chemical Corporation (Sinopec) and energy trader Zhuhai Zhenrong Corp aim to jointly extract about 500,000 barrels per day of crude from Iran in 2016 (Mehr News Agency [Tehran], February 14; Platts, January 25; Reuters, December 3, 2015).

Public affirmations of friendship notwithstanding, Sino-Iranian relations are not without their hurdles. The absence of foreign competition afforded China with a tremendous advantages relative to its Western competitors in terms of accessing the Iranian market. In 2013, Iran terminated its $2.5 billion contract with the China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC), China’s largest oil and natural gas concern, to conduct upstream development on the Azadegan oil field in southwestern Iran’s Khuzestan Province and another project at the South Pars offshore natural gas field after CNPC failed to begin work on the project. CNPC’s inaction was attributed to a decision to appease the United States and to curry favor with U.S. energy producers. Iran has since suggested that CNPC may once again be invited back to develop Azadegan. In light of the prospect of contending with new competition, there are indications that China is ramping up its operations in order to mollify Iran’s concerns (Press TV, January 3, 2016; Press TV, August 1, 2015). The former sanctions regime also afforded China preferential status as far as the share of Iran’s consumer goods market and in other non-energy-related sectors. This undermined many Iranian industries and small businesses. Chinese goods are likely to retain their competitive edge in the near- to medium-terms, although the availability of Western-origin goods will chip away at China’s edge in the long-term (National Interest, July 28, 2015).

Defense

The prospect of increased cooperation between China and Iran in the defense sector, especially in the form of Chinese arms sales to Iran, constitutes another area of potential cooperation that is receiving more attention in light of the removal of sanctions on Iran. China and Iran share a long history of defense contacts going back to the Iran-Iraq War, although the scale of their cooperation in tangible terms is often overstated. China’s support to Iran over the years has included varying degrees of technological assistance for its nuclear and ballistic missile programs and transfers of advanced platforms, including the HY-2 Silkworm anti-ship cruise missiles and fast attack boats that are integral to Iran’s Area Access/Area Denial (A2/AD) military doctrine. The pace of military-to-military contacts between China and Iran has also witnessed a notable surge in recent years (China Brief, February 5, 2015).

The sanctions regime crippled Iran’s ability to procure critical conventional weapons platforms, as well as technological expertise and necessary spare parts. For example, the Islamic Republic of Iran Air Force’s (IRIAF) modest air capabilities rely on antiquated U.S.-origin air platforms such as the F-4 and F-14 purchased before the 1979 Islamic Revolution and similarly outdated Soviet-, French- and Chinese-origin aircraft such as the F-7 fighter (Fars [Iran], February 7, 2015). Through the means of reverse engineering, the cannibalization of spare parts, and ingenuity, Iran’s domestic military industrial complex has compensated for its lack of access to weapons markets and technology. Indeed, Iran’s conventional and technological deficiencies have helped mold its operational military strategy around the asymmetric and irregular warfare concepts it relies on so heavily today. With the removal of sanctions, Iran is eager to modernize its military and keep pace with its regional rivals through purchases of foreign arms. Iran is surrounded by some of the world’s largest importers of advanced conventional weapons systems, including Israel, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, and Pakistan (Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, February 22). Iran is also faced with a heavy U.S. military footprint in the form of a network of military bases and deployments of air and naval assets that serve to contain and deter its actions. Given its security environment, it is no surprise why Iran has prioritized the modernization of its conventional military capabilities following the implementation of the JCPOA.

Iran has already engaged Russia in the hope of procuring a host of modern defense systems, including late generation fighter aircraft, helicopters, armor, air defense systems, and naval assets (Eurasia Daily Monitor, February 18). There are reports that Iran and China have explored the possibility of Iran purchasing 150 of China’s J-10 stealth fighter and a host of other modern weapons systems (People’s Daily Online, August 13, 2015).

Conclusion

While the full implications of the JCPOA on Iran’s regional and international standing have yet to be realized, the outcome of Xi’s visit to Tehran is likely to presage years of continued Sino-Iranian engagement and cooperation. At the same time, China is steadily being confronted with outside competition for Iran’s most promising markets and similar challenges. In terms of its history of dealings with Iran in recent years, this represents unfamiliar territory for China.

Chris Zambelis is a Senior Analyst specializing in Middle East affairs for Helios Global, Inc., a risk management group based in the Washington, D.C. area. He is also the director of World Trends Watch, Helios Global’s geopolitical practice area. The opinions expressed here are the author’s alone and do not necessarily reflect the position of Helios Global, Inc.