China Eyes Greater Share of Turkey’s Rising Infrastructure Investments, Including Construction of a Nuclear Plant

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 9 Issue: 43

By:

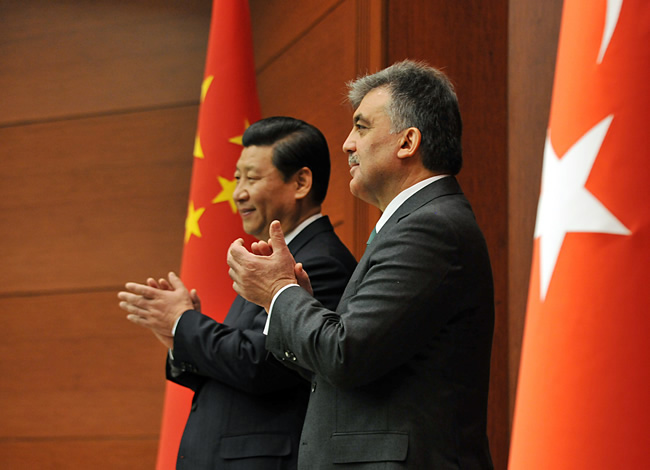

China’s Vice President Xi Jinping’s visit to Turkey, where he held several meetings with Turkish leaders, has underlined the growing economic ties and diplomatic exchanges between the two countries, despite their failure to develop joint positions on political issues. Xi met Turkey’s president and prime minister, and participated in the Turkey-China Economic and Commercial Cooperation Forum.

A large part of Xi’s contacts pertained to economic cooperation, which is understandable given that the two countries have been the most rapidly growing economies in the world in the wake of the global financial crisis. Their bilateral trade volume reached $24 billion in 2011, while it was only $1 billion at the beginning of the decade. However, the trade balance is tilted dis-proportionally in Turkey’s disfavor. One factor that helps correct this unhealthy picture is the growing Chinese interest in the Turkish economy. Chinese companies have been increasingly undertaking contracting services in Turkey, including plans for the construction of major railway networks. As Turkey plans to initiate other multi-billion dollar infrastructure projects, China is increasingly interested in getting a larger share of this pie. A delegation of businessmen accompanying Xi signed various agreements with their Turkish counterparts pertaining to Turkish exports, financial support by Chinese firms and energy investments, again reflecting the rising volume of Chinese investments in Turkey.

During the visit, it was even mentioned by both parties to raise the bilateral trade volume to $100 billion over the next ten years or so (Anadolu Ajansi, February 23). While setting that target, however, the Turkish side complained about its inability to penetrate the Chinese market and called on China to take some measures that would help reduce the trade imbalance. One particular measure that was agreed upon during the visit would allow the central banks of the two countries to carry out a three-year currency swap agreement, worth $1.6 billion.

Reportedly another item on the agenda was cooperation in peaceful nuclear technology. Following the business forum meeting, Deputy Prime Minister Ali Babacan said that Turkey’s Energy Ministry will start a dialogue with its Chinese counterpart on China’s construction of a nuclear power plant in Turkey (Anadolu Ajansi, February 22). In an effort to reduce its heavy dependence on hydrocarbons, as part of its energy strategy documents, Turkey has been planning to build up to three nuclear power plants. Short of possessing genuine technology, it has been seeking actively to develop partnerships with other countries in this field. Turkey has already signed an intergovernmental agreement with Russia pertaining to the first nuclear power plant, and the negotiations are under way with Japan and South Korea for the second one. China too has been very active in building many nuclear plants to meet its energy needs, which have increased due to its fast growing economy, and is now seeking to build power plants abroad.

Though Turkey’s possible partnership with China in nuclear energy might make sense from a diversification point of view, awarding tenders to different countries also raises the question to what extent this will be an efficient strategy from the technology accumulation perspective. Granted, Turkish press maintained that China was ready to undertake the tender for the construction of the power plant through a $20 billion-worth foreign direct investment (Sabah, February 25). If this deal is realized, it will mark the largest single FDI flow into Turkish economy, which would also signify China’s trust in Turkey’s economic performance.

However, the dynamics of Turkish-Chinese economic ties and their reflection in the political realm resemble very much Turkey’s somewhat problematic ties with Russia and Iran. At one level, Turkey’s economic relations with these three powers underscore the inherent shortcomings of Turkey’s growth model. While Turkey is running a huge trade deficit vis-à-vis Russia and Iran due to energy imports, its trade with China also has been similarly problematic, due to the import of consumer goods. Despite record growth rates in recent years, many experts warn that Turkey’s economic miracle is driven by domestic demand rather than exports, and its current account deficit poses a big vulnerability to an economic shock. As part of its commercial strategy of developing multi-dimensional partnerships with neighbors and other rising powers, Turkey has been quite intent on boosting the bilateral trade volume with various nations. However, short of a major restructuring of the underlying dynamics of Turkey’s economy so that it becomes more competitive and gains access to energy resources at reasonable costs, increasing the trade volume with other countries will not help Turkey become a major power house.

At the political level, too, there are similarities between Turkish-Chinese relations and Ankara’s relations with Moscow and Tehran. The growth of its trade volume with Russia and Iran neither helped Ankara forge a common position with these countries on regional issues, nor could it gain from them a more receptive attitude toward its demands in some economic and political issues. With China, too, the expansion of economic ties was partly a product of Ankara’s refrain from raising the thorny issue of the East Turkestan and the plight of the Uighur people. Moreover, as was demonstrated in the case of Beijing’s position on the Syrian regime’s violent suppression of the popular uprising, Turkey and China have not converged politically. The obvious political differences have not prevented Ankara from pursuing cooperation and enhanced diplomatic exchanges with Beijing.

After Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s harsh reaction to China’s policies in Xinjiang in 2009, which caused a political friction, Turkey increasingly watered down its criticism, which opened the way for bolstering bilateral relations. Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoglu’s visit to China and Chinese Premier Wen Jiabo’s visit to Ankara in 2010 were such major occasions, and Erdogan is expected to visit China this year. The year 2012 is being celebrated as the Year of Turkey in China, while next year the Year of China will be celebrated in Turkey. It appears that Turkey is determined to maintain a high dose of pragmatism and commercially-driven thinking which have shaped its policy toward China, as well as other rising powers.