China Unveils “The Kashmir Card”

Publication: China Brief Volume: 10 Issue: 19

By:

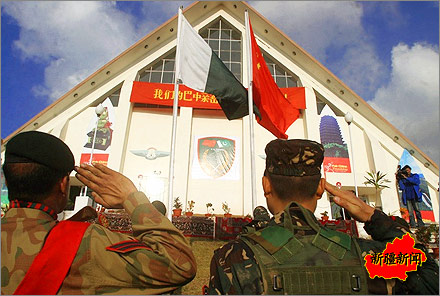

Even as the Chinese navy signals its intent to enforce sea denial in the "first island chain" in the East (comprised of the Yellow Sea, the East China Sea and the South China Sea of the Pacific Ocean), the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) is reportedly on the move along China’s southwest frontier in Pakistani-held Kashmir. In late August, media accounts reported the presence of thousands of Chinese troops in the strategic northern areas (renamed Gilgit-Baltistan in 2009 by Pakistan) of Pakistani-held Kashmir bordering Xinjiang province. A Western report suggested that Islamabad had ceded control of the area to Beijing, prompting denials from both capitals (New York Times, August 26). Chinese Foreign Office spokesperson Jiang Yu denied the story, saying the troops are there to help Pakistan with flood relief work" (China Daily, September 2). Nonetheless, credible sources confirm the presence of the PLA’s logistics and engineering corps to provide flood relief and to build large infrastructure projects worth $20 billion (railways, dams, pipelines and extension of the Karakoram Highway) to assure unfettered Chinese access to the oil-rich Gulf through the Pakistani port of Gwadar. As China’s external energy dependency has deepened in the past decade, so has its sense of insecurity and urgency.

"The Kashmir Card"

While China and India have long sparred over the Dalai Lama and Tibet’s status, border incursions and China’s growing footprint in southern Asia, a perceptible shift in the Chinese stance on Kashmir has now emerged as a new source of interstate friction. Throughout the 1990s, a desire for stability on its southwestern flank and fears of an Indian-Pakistani nuclear arms race caused Beijing to take a more evenhanded approach to Kashmir, while still favoring Islamabad.

Yet, in a major policy departure since 2006, Beijing has been voicing open support to Pakistan and the Kashmiri separatists through its opposition to the UN Security Council ban on the jihadi organizations targeting India, economic assistance for infrastructure projects in northern Kashmir, and the issuance of separate visas by Chinese embassies to Indian citizens of Kashmiri origins [1].

Amidst the current unrest in the valley, Beijing has also invited Kashmiri separatist leaders for talks and offered itself as a mediator, ostensibly in a tit-for-tat for India’s refuge to the Dalai Lama [2]. Yet, China is actually the third party to the dispute in Jammu and Kashmir (J&K). While India holds about 45 percent and Pakistan controls 35 percent, China occupies about 20 percent of J&K territory (including Aksai Chin and the Sakshgam Valley ceded by Pakistan to China in 1963). The denial of a visa in July 2010 to Indian Army’s Northern Command General B. S. Jaswal who was to lead the 4th bilateral defense dialogue in Beijing because he commanded "a disputed area, Jammu and Kashmir," is said to be the last straw that broke the camel’s back.

Consequently, a new chill has descended on Sino-Indian relations. India retaliated by suspending defense exchanges with China and lodging a formal protest. New Delhi sees these moves as part of a new Chinese strategy with respect to Kashmir that seeks to nix its global ambitions and entangle India to prevent it from playing a role beyond the region. Prime Minister Manmohan Singh told Indian media, "Beijing could be tempted to use India’s ‘soft underbelly’, Kashmir, and Pakistan ‘to keep India in low-level equilibrium’" (Times of India, Sep 7).

Resurrecting old issues and manufacturing new disputes to throw the other side off balance and enhance negotiating leverage is an old negotiating tactic in Chinese statecraft. The downturn in Sino-Indian ties since the mid-2000s may be partly attributed to the weakening of China’s "Pakistan card" against India, necessitating the exercise of direct pressure against the latter. Beijing fears that an unrestrained Indian power would eventually threaten China’s security along its southwestern frontiers. One Chinese analyst maintains, "Beijing would not abandon its ‘Kashmir card’. The Kashmir issue will remain active as long as China worries about its southern borders" (Asia Times online, December 4, 2009). China and Pakistan have been allies since the 1962 Sino-Indian conflict. This enduring alliance was formalized with the conclusion of the China-Pakistan "Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation and Good Neighborly Relations" in April 2005.

Likewise, the sharper focus on Tawang is part of a shriller claim over Arunachal Pradesh in the east, which Beijing now calls "South Tibet" (a new Chinese term for Arunachal Pradesh since 2005), ostensibly to extend its claim over the territories [3]. It is worth noting that prior to 2005, there was no reference to "Southern Tibet" in China’s official media or any talk of the "unfinished business of the 1962 War." Nor did the Chinese government or official media ever claim that the PLA’s "peaceful liberation of Tibet in 1950 was partial and incomplete" or that "a part of Tibet was yet to be liberated." Taking a cue from the Pakistanis, who have long described Kashmir as the "unfinished business of the 1947 partition," Chinese strategists now call Arunachal Pradesh, or more specifically, Tawang, the "unfinished business of the 1962 War" (Global Times, November 9, 2009). China also sought to internationalize its bilateral territorial dispute with India by opposing an Asian Development Bank loan in 2009, part of which was earmarked for a watershed project in Arunachal Pradesh [4].

Chinese strategic writings indicate that as China becomes more economically and militarily powerful, Beijing is devising new stratagems to keep its southern rival in check. Some Chinese economists calculate that within a decade or so India could come close to "spoiling Beijing’s party of the century" by outpacing China in economic growth (Bloomberg News, Aug 15). From Beijing’s perspective, India’s rise as an economic and military power would prolong American hegemony in Asia, and thereby hinder the establishment of a post-American Sino-centric hierarchical regional order in the Asia-Pacific.

The last decade has, therefore, seen the Chinese military bolstering its strength all along the disputed borders from Kashmir to Burma (aka Myanmar). Beijing also prefers a powerful and well-armed Pakistani military, as that helps it mount pressure, by proxy, on India. China continues to shower its "all-weather" friend with military and civilian assistance from ballistic missiles to JF-17 fighter aircraft, from nuclear power plants to infrastructure. Having "fathered" Pakistan’s nuclear weapons program, China is now set to "grandfather" Pakistan’s civilian nuclear energy program as well (The Telegraph, June 21; The Diplomat, June 17; Nuclear Energy Brief, April 27). Chinese and Pakistani strategists gloat over how Beijing is building naval bases around India that will enhance Chinese naval presence in the Indian Ocean [5]. However, the best-laid plans might come unstuck if Pakistan fails to pacify Balochistan Province, where Gwadar is located. The growing Balochi independence movement, which has repeatedly targeted Chinese engineers since 2004, makes the Chinese nervous about implementing their proposals for investment in the construction of a petrochemical complex, a pipeline and a railway line.

Mutual suspicions, geopolitical tensions, and a zero-sum mentality add to a very competitive dynamic in the China-Pakistan-India triangular relationship. Beijing and Islamabad are concerned over the growing talk in Washington’s policy circles of India as emerging as a counterweight to China on the one hand and the fragile, radical Islamic states of Southwest Asia on the other, viewing a potential U.S.-Indian alignment with horror. The U.S. military bases in Afghanistan and Pakistan, and India’s growing footprint in Afghanistan cause alarm in Beijing and Islamabad. Some Chinese strategists worry about the destabilizing consequences of a prolonged U.S. military presence in "Af-Pak" on the future of Sino-Pakistan ties, as well as on Pakistan’s domestic stability. While the remarkable upturn in Indian-American security ties has exacerbated the security dilemma, the post-9/11 U.S. military presence in Pakistan has sharpened the divide within the Pakistani military into pro-West and pro-Beijing factions [6].

A geopolitical crisis of Himalayan proportions may well be in the making from Afghanistan to Burma. The Chinese state-run media have begun to attack India for supposedly hegemonic designs, with some hinting at the merits of a confrontation [7]. Beijing perceives India as the weakest link in an evolving anti-China coalition of maritime powers (the U.S.-Japan-Vietnam-Australia-India) inimical to China’s growth. The real irony is that China and India could stumble into another war in the future for exactly the same reasons that led them to a border war half-a-century ago in 1962.

New railroad infrastructure projects in Pakistani-held Kashmir and Tibet are aimed at bolstering China’s military strength and intervention options against India in the event of another war between the sub-continental rivals or between China and India. Most war-gaming exercises on the next India-Pakistan war end either in a nuclear exchange or in a Chinese military intervention to prevent the collapse of Beijing’s "all-weather ally" in Asia. Although the probability of an all-out conflict seems low, the China-Pakistan duo and India will employ strategic maneuvers to checkmate each other from gaining advantage or expanding spheres of influence (The Telegraph, Sep 14). According to one Chinese analyst, Dai Bing: "While a hot war is out of the question, a cold war between the two countries is increasingly likely" (China.org.cn, February 8).

Beijing’s nemesis: Islam and Buddhism

Having said that, Beijing’s new Kashmir activism goes beyond the strategic imperative to contain India. China’s relationship with Pakistan is also aimed at countering the separatist threats in its western Muslim-majority Xinjiang province. Much like Tibetan Buddhism, Beijing views radical Islam as a strategic threat to China’s national integrity, particularly in Xinjiang (formerly East Turkestan), where the East Turkestan Islamic Movement is fighting for an independent homeland for several decades. Frequent disturbances and protests in Xinjiang and Tibet make the issue more acute insofar as they show how vulnerable the Chinese hold is over its western region.

The spillover effects of rabid Talibanization of Pakistani society worry the Chinese (The Australian, July 25). The past few years have seen Chinese civilians working in Pakistan kidnapped and killed by Islamic militants, partly in retaliation against Beijing’s "strike hard" campaigns against Uyghur Muslims and partly in protest against Beijing’s resource extraction and infrastructure development projects in Pakistan’s Wild West. Beijing has repeatedly impressed on Islamabad the importance of tightening control over its porous border with China (Pak Tribune, July 18). Should Islamabad fail to stem the radicalization and training of Uyghur separatists on its territory, it risks undermining the strategic relationship with China. Significantly, the Gilgit-Baltistan in northern Kashmir is where the predominantly Sunni Pakistan Army is faced with a revolt from the local Shiite Muslims.

For its part, Pakistan has always been extraordinarily sensitive to Chinese interests. Islamabad essentially "carries the water" for China in the Islamic world. Pakistan played a key role in selling China’s point of view on the July 2009 riots in Xinjiang, which resulted in 183 deaths. Pakistan has ensured that the Organization of Islamic Countries (OIC) does not pass any resolution condemning China’s "strike hard" campaigns (including curbs on the observance of Ramadan) against its Uyghur Muslim minority. In return, China has repeatedly used its UN Security Council seat to ensure that no harm comes to Pakistan for sheltering anti-Indian terrorist groups (Pak Tribune, July 8; The American Interest, May-June 2010). Further, Islamabad offers unequivocal support for Beijing’s position on every single issue in international forums, from Tibet and Taiwan to trade and the U.N. Security Council reforms.

Tightening embrace

A high degree of mistrust and conflicting relations between India and its smaller South Asian neighbors provide Beijing with enormous strategic leverage vis-à-vis its southern rival. China’s strategic leverage thus prevents India from achieving a peaceful periphery via cross-border economic, resource and transportation linkages vital for optimal economic growth. Interestingly, Chinese strategic writings reveal that Pakistan and Burma have now acquired the same place in China’s grand strategy in the 21st century that was earlier occupied by Xinjiang (meaning "New Territory") and Xizang (meaning "Western treasure house," that is, Tibet) in the 20th century [8]. Stated simply, following the integration of outlying provinces of Xinjiang and Xizang (Tibet) into China, Pakistan is now being perceived as China’s new "Xinjiang" (new territory) and Burma as China’s new "Xizang" (treasure house) in economic, military and strategic terms. Beijing’s privileged access to markets, resources and bases of South Asian countries has the additional benefit of making a point on the limits of Indian power.

Conclusion

Both enmity and amity between India and Pakistan have significant implications for China’s grand strategy. A hostile stance toward India reassures the Pakistani establishment of China’s unstinted support in Islamabad’s domestic and external struggles. It also throws a spanner in the works of any U.S.-facilitated India-Pakistan accommodation over the Kashmir imbroglio. In the triangular power balance game, the Sino-Pakistan military alliance (in particular, the nuclear and missile nexus) is aimed at ensuring that the South Asian military balance-of-power remains pro-China. Nurturing Pakistani military’s fears of Indian dominance helps Beijing keep Islamabad within its orbit.

However, Pakistan today is facing a "perfect storm" of crises, with its U.S.-backed fight against al-Qaeda and the Taliban faltering and the country lurching toward bankruptcy. The linchpin of Beijing’s South Asia strategy is potentially a "wild card" because Pakistan’s possible futures cover a wide spectrum: from the emergence of a moderate, democratic state to a radical Islamic republic to "Lebanonization." If it does not implode or degenerate into another Iran or Afghanistan (a radical Islamic and/or a failed state), and gets its house in order, Pakistan could emerge as a pivotal player in the U.S.-Chinese-Indian triangular relationship. Despite Beijing’s disenchantment with the current state of its "time-tested ally," China remains committed to supporting Pakistan. If anything, Pakistan’s transformation from being an ally to a battleground in the U.S.-led War on Terror has forced Islamabad into an ever-tighter embrace of China.

Notes

1. S. Fazl-e-Haider, "China’s growing stake in Pakistan," Asia Times online, November 30, 2006, https://www.atimes.com/atimes/South_Asia/HK30Df01.html; A. Small, "China’s Caution on Afghanistan-Pakistan," Washington Quarterly, 33:3 (July 2010): 89.

2. B. Raman, "Dealing With Chinese Machinations on J & K," C3S Paper No.574, August 28, 2010, https://www.c3sindia.org/uncategorized/1587l; M. Atal, "China’s Pakistan Corridor," Forbes Asia, April 30- May 10, 2010.

3. "Future directions of the Sino-Indian border dispute," International Strategic Studies [Guogji Zhanlue], November 2006; Zhongguo Zhanlue, "Zhenggao Indu zhengfu: Buyao yiyuan baode" (CIIS, "A Warning to the Indian Government: Don’t Return Evil For Good"), March 26, 2008, https://str.chinaiiss.org/content/2008-3-26/26211952.shtml; Liu Silu, "Beijing Should Not Lose Patience in Chinese-Indian Border Talks," ("Zhongyin bianjie tanpan, Beijing bu neng ji"), Wen Wei Po (Hong Kong), June 1, 2007.

4. Interestingly, however, Beijing vehemently opposes Southeast Asian countries’ efforts to internationalize their multilateral dispute over the Spratlys in the South China Sea.

5. Discussions with diplomats and regional specialists, 2007–09.

6. Ibid.

7. See "How Likely is China’s Launch of a Limited War Against India?" People’s Daily Forum, https://www.peopleforum.cn/viewthread.php?tid=34509&extra=page%3D1.

8. Liu Naiqiang, "China’s Energy Diplomacy Faces Challenges Ahead," Nanfeng Chuang [Guangzhou], November 16, 2007, 22-24; Shen Dingli, "Don’t shun the idea of setting up overseas military bases," China.org.cn, January 28, 2010, https://www.china.org.cn/opinion/2010-01/28/content_19324522_3.htm; "An analysis of Chinese and Indian navies’ long-distance sea endurance capabilities," ["Zhong yin hai jun yuan hai jian di shi li dui bi de shen du fenxi"], May 7, 2008, https://bbs.chinaiiss.org/dispbbs.asp?boardID=78&ID=129008&page=1.