China’s SSBN Forces: Transitioning to the Next Generation

Publication: China Brief Volume: 9 Issue: 12

By:

China’s undersea deterrent is undergoing a generational change with the emergence of the Type-094, or Jin-class, which represents a substantial improvement over China’s first-generation Type-092, or Xia-class, nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine (SSBN). Launched in the early 1980s, the People’s Liberation Army Navy’s (PLAN) single Xia-class SSBN (hereafter Xia) has never conducted a deterrent patrol and is equipped with relatively short-range (1,770 km) JL-1 SLBMs (submarine-launched ballistic missiles). In contrast, China may build five Type-094 SSBNs, which will enable the PLAN to conduct near-continuous deterrent patrols, and each of these second-generation SSBNs will be outfitted with 12 developmental JL-2 SLBMs that have an estimated range of at least 7,200 km and are equipped with penetration aids. Although the transition to the new SSBN is ongoing, recent Internet photos depicting at least two Jin-class SSBNs (hereafter Jin) suggest that the PLAN has reached an unprecedented level of confidence in the sea-based leg of its strategic nuclear forces. Indeed, China’s 2008 Defense White Paper states that the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) is enhancing its “nuclear counterattack” capability [1]. With the anticipated introduction of the JL-2 missiles on the Jin and the deployment of DF-31 and DF-31A road-mobile intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), China is on the verge of attaining a credible nuclear deterrent based on a ‘survivable’ second-strike capability.

Recent Developments

The U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) assesses that China will build a “fleet of probably five Type-094 SSBNs . . . to provide more redundancy and capacity for a near-continuous at-sea presence” [2]. A variety of Chinese publications suggest that the SSBN forces of France and Britain—which have four vessels each, with one at sea at all times, two in refit, and one under maintenance—may serve as models for China and hence reinforce the aforementioned indications of its plans. One Chinese source, however, suggests that China will field six Type-094 SSBNs, divided into patrolling, deploying and refitting groups [3], with another assessment suggesting that these groups will comprise two SSBNs each [4].

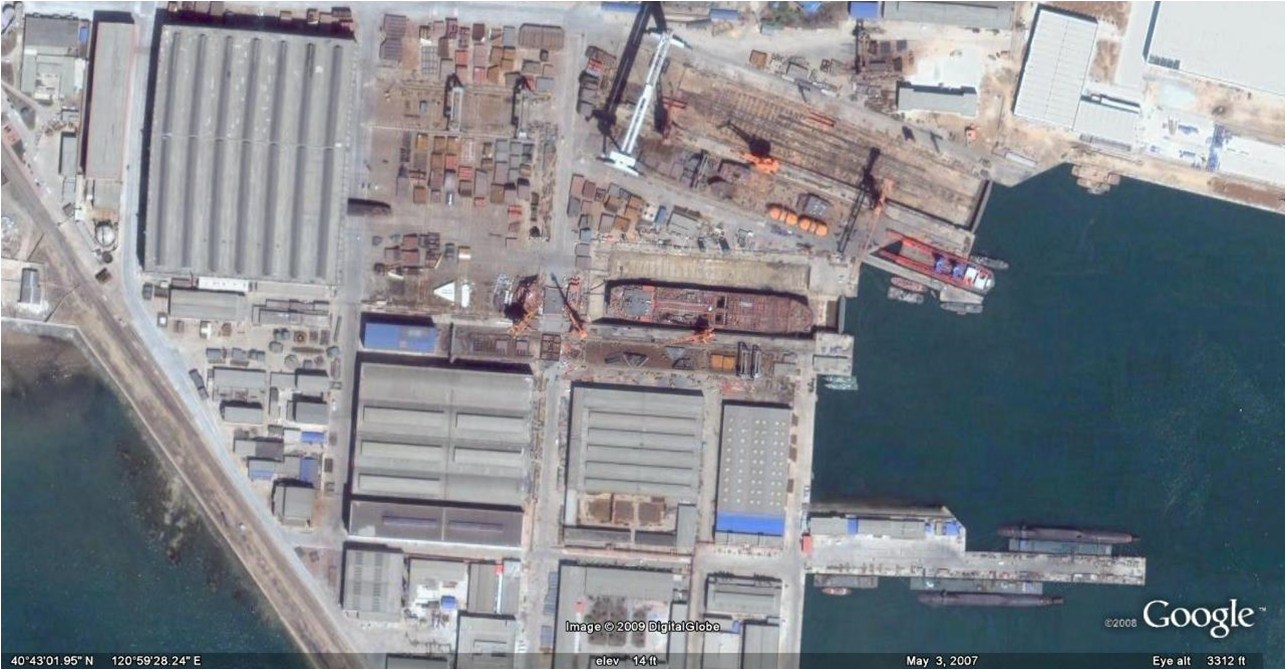

It is clear that at least two different hulls have already been launched, based on unusually high-resolution internet and commercial satellite images that have emerged of one Jin in port at Xiaopingdao base, south of Dalian, two Jins in the water and perhaps one emerging from production at Huludao base east of Beijing, and one at a newly-constructed submarine facility at Yalong Bay near Sanya on Hainan Island. The images of the facility on Hainan Island provided some hints as to the PLAN’s SSBN basing plans. Indeed, the photo of the Jin at Yalong Bay suggests that the facility may be the base for China’s future SSBN forces.

Development Motives

Many Western analysts have focused on the ‘survivability’ issue to explain China’s decision to proceed with the development of the Jin and the JL-2. Given the potential vulnerability of Chinese SSBNs to detection by adversary attack submarines and the challenges of locating dispersed road-mobile missiles, however, it would certainly seem that Chinese decision-makers must also have been considering other factors, including missile defense, international prestige and inter-service politics.

Chinese strategists appear to calculate that a nuclear dyad, composed of land-based strategic missiles and SLBMs, or possibly a triad incorporating nuclear-armed PLAAF bombers as well, is required to enhance the credibility of China’s nuclear deterrent in line with the requirements of the “effective counter-nuclear deterrence” posture discussed in recent Chinese publications. Chinese analysts assert that an SSBN is “the most survivable type of (nuclear) weapon” [5], and hint that it may allow China to deter third party intervention in a regional conflict. Citing the development of the Jin, one Chinese source states, “If a war erupts across the Taiwan Strait one day, facing the danger of China waging nuclear war, it will be very difficult for America to intervene in the cross-strait military crisis” [6]. The authors interpret the Chinese comments here to mean not that China would be likely to launch nuclear weapons first in response to U.S. intervention in a China-Taiwan conflict, but rather that Chinese analysts believe strong SSBN capabilities would enhance its deterrence posture by causing Washington to think twice about intervening in a conflict in which escalation control might be difficult.

Another potential explanation for the investment in the development of the Jin is that Chinese planners believe SLBMs launched from certain patrol areas might complicate U.S. missile-defense interception efforts. A Chinese analysis states that SSBNs “are more capable of penetrating [missile] defenses” [7].

Yet another plausible explanation for the decision to deploy the Jin is that Chinese leaders may view the ships as symbols of China’s emerging great-power status. The other permanent members of the U.N. Security Council—France, Britain, Russia, and the United States—all have modern SSBNs in their fleets, and Beijing may see the deployment of its own as a way to enhance its international prestige. This certainly appears to be true of nuclear-powered submarines in general. Indeed, former PLAN Commander Admiral Liu Huaqing and others have stated that nuclear submarines represent one of China’s clearest claims to great power status [8].

Still another possible explanation is inter-service politics. Although the politics of China’s defense budget process are opaque to outsiders, it seems reasonable to speculate that the PLAN leadership may have pushed for the development of the Jin to ensure that the navy would have a role to play in the strategic nuclear-deterrence mission.

Operational Challenges

Notwithstanding the considerable progress reflected by the launching of at least two Jin SSBNs, the PLAN still faces at least three key challenges before it realizes a secure seaborne second-strike capability: reducing the probability of detection; at-sea training of commanders and crew members; and coping with the nuclear command-and-control issues associated with the operation of SSBNs.

Chinese observers are well aware of the challenges of avoiding detection, as reflected by their analysis of capabilities allegedly demonstrated during the Cold War vis-à-vis Soviet submarines. Subsequent-generation submarines are generally significantly quieter than those of earlier generations, so it may be expected that China has made progress in quieting its submarines as well. Nevertheless, the Jin is still a second generation SSBN, and those of other nations have faced significant acoustic difficulties.

Training is another potential challenge for China’s emerging SSBN force. Although digital training and simulations can be useful, the only way other nations have become proficient at submarine operations is by taking their boats to sea. Chinese naval exercises have increased in sophistication in recent years and currently encompass such categories as command and control, navigation, electronic countermeasures, and weapon testing. Moreover, Chinese submarine patrols have increased in recent years—the PLAN conducted 12 patrols in 2008, twice as many as in 2007 [9]. This increase in patrols and the overall priority accorded to China’s submarine force development suggest that the PLAN’s submarines are now able to range farther afield on a more frequent basis. Indeed, the evolving missions and growing capabilities of the Chinese submarine force “create the conditions for Beijing to opt for an increased submarine presence in the Western Pacific east of the Ryukyu Island chain” [10].

While the trajectory of training specifically relevant to deterrent patrols remains opaque, the PLAN is striving to improve the rigor and realism of education and training across the board. Within this context, submarines have clearly been an area of emphasis and the PLAN is using a variety of methods to prepare its sailors for future wars. Official Chinese publications note, for example, that various types of simulators have been used to improve submarine training.

Establishing and maintaining secure and reliable communications with SSBNs constitutes another major challenge for any country that desires a sea-based deterrent. Chinese military publications emphasize that the central leadership must maintain strict, highly-centralized command and control of nuclear forces. China’s submarine force has reportedly employed high-frequency (HF), low-frequency (LF), and very-low-frequency (VLF) communications, and researchers are working on a number of technologies that could be useful for secure communications with submarines, as reflected by recent publications discussing the prevention of enemy detection of transmissions between submarines and shore-based headquarters units. Ensuring the ability to communicate with SSBNs in an environment in which an adversary may attempt to disrupt its command and control system could be a critical challenge for the PLAN. It remains unclear, however, to what extent centralized SSBN command, control, and communication is possible for China across the range of conflict scenarios.

Beyond the problem of ensuring secure and reliable communications, the deployment of SSBNs also entails use-control challenges. Given the strong emphasis on centralized control of nuclear forces that is evident in official Chinese military and defense policy publications, it seems highly unlikely that the PLAN would conduct deterrent patrols without effective use controls. Presumably, China will strive not only to develop a communications capability that is robust enough to ensure at least one-way wartime connectivity between Beijing and the Jin-class SSBNs, but also to minimize the possibility of an accidental or unauthorized launch by implementing some combination of technical and procedural controls.

Conclusion

Notwithstanding the recent series of revelations about China’s emerging SSBN force, at least four questions that have major implications for the future of China’s sea-based deterrent remain unanswered. First, there is the issue of how many SSBNs China will ultimately build, which will influence China’s ability to conduct continuous or near-continuous deterrent patrols. Second, it remains unclear whether China will attempt to create bastions for its SSBNs in areas close to the mainland or deploy them to more distant patrol areas—a decision which will no doubt be informed in part by the capabilities of the JL-2 SLBM, which remains under development. Third, little is known about China’s plans for coping with the command and control challenges associated with the deployment of a sea-based deterrent force, which could influence crisis stability. Fourth, authoritative Chinese sources refer to “joint nuclear counter-attack campaigns” in which the Second Artillery’s nuclear missile force, PLAN SSBNs, and nuclear-capable Chinese air force bomber units would all participate, but it remains unclear to what extent China will actually integrate its emerging SSBN force into a joint strategic nuclear deterrence capability [11]. While these uncertainties remain, the investment already made in SSBN hulls and shore facilities indicates that the program represents a major effort to move beyond the ill-fated Xia and take China’s nuclear deterrent to sea. In addition, the emergence of photos showcasing at least two Type-094 submarines—which reflects Beijing’s apparent willingness to allow Western analysts to see them—may signal a new level of confidence on Beijing’s part, and perhaps even a nascent recognition that modest increases in transparency could actually support rather than undermine China’s strategic interests.

Notes

1. “China’s National Defense in 2008” (Beijing: State Council Information Office, January 2009), https://merln.ndu.edu/whitepapers/China_English2008.pdf.

2. Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI), “Seapower Questions on the Chinese Submarine Force,” 20 December 2006, https://www.fas.org/nuke/guide/china/ONI2006.pdf.

3. Jian Jie, “The Legend of the Virtuous Twins,” World Outlook, no. 448 (August 2002), p. 23.

4. Lin Changsheng, “The Combat Power of China’s Nuclear Submarines,” World Aerospace Digest, no. 103 (September 2004), p. 33.

5. Zhang Feng, “Nuclear Submarines and China’s Navy,” Naval & Merchant Ships (March 2005), p. 12.

6. “China’s at Sea Deterrent,” Military Overview, no. 101, p. 53.

7. Wang Yifeng and Ye Jing, “What the Nuclear Submarine Incident Between China and Japan Tells Us About the Ability of China’s Nuclear Submarines to Penetrate Defenses, Part 1,” Shipborne Weapons (January 2005), pp. 27–31.

8. Liu Huaqing, The Memoirs of Liu Huaqing (Beijing: People’s Liberation Army Press, 2004), p. 476.

9. Hans Kristensen, “Chinese Submarine Patrols Doubled in 2008,” Strategic Security Blog, February 3, 2009, https://www.fas.org/blog/ssp/2009/02/patrols.php.

10. Office of Naval Intelligence, “Seapower Questions on the Chinese Submarine Force.”

11. Yu Jixun, chief ed. et al., People’s Liberation Army Second Artillery Corps, The Science of Second Artillery Campaigns (Beijing: PLA Press, 2004), pp. 297-298.