China’s Vaccine Diplomacy Revamps the Health Silk Road Amid COVID-19

China’s Vaccine Diplomacy Revamps the Health Silk Road Amid COVID-19

Introduction

As global COVID-19 cases exceed 51 million, a top health official from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has predicted that China is “very likely” to avoid a winter coronavirus outbreak, adding that the coronavirus situation in China was “very safe overall” (Caixin, November 11). The head of China’s Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CCDC) expressed similar optimism in September when he noted that widespread vaccinations likely would not be necessary in China due to the country’s effective control of the outbreak (SCMP, September 13).

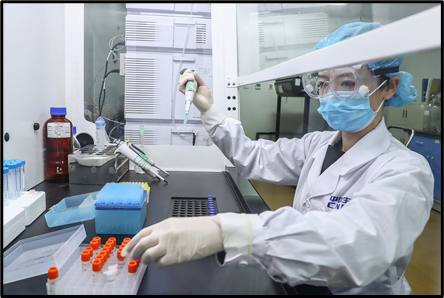

At the same time, Chinese researchers have raced to develop a viable COVID-19 vaccine, sometimes skirting vaccine development norms in the process and already inoculating hundreds of thousands of people under “emergency use authorizations” (Caixin, September 8).[1] While countries experiencing high coronavirus caseloads in the West have reportedly stockpiled pre-purchases of vaccines, Chinese Communist Party (CCP) General Secretary and PRC President Xi Jinping has repeatedly pledged to make a COVID-19 vaccine “a global public good”, available to all (Xinhua, May 18).

Chinese Vaccine Diplomacy

China made headlines in October when it signed on to COVAX, a UN-led program aiming to promote equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines for developing countries (CGTN, October 9). But with large states such as the U.S. and Russia failing to sign on to the initiative, COVAX has failed to raise even a tenth of the $35 billion that is needed to successfully scale up vaccine distribution worldwide (WHO, September 21). In separate deals, Chinese leaders have promised to provide $1 billion in loans to help Latin American and Caribbean countries purchase vaccines (China Daily, July 27), and to distribute free vaccines across Africa and Southeast Asia (Xinhua, June 18; Asia Times, August 26). For some countries, China promised to provide vaccines in return for aid in carrying out safety trials (The News (PK), August 14; Yicai Global, October 16).[2] For others, promises of vaccine doses have been connected with pressures to agree to specific foreign policy objectives, echoing the strings often attached to China’s heavy-handed “mask diplomacy” earlier in the pandemic.[3]

After stumbling in its initial response to the coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, the Chinese government has boldly leveraged the chaos of the pandemic to pursue strategic gains at the expense of longstanding norms: challenging territorial designations along the Indian border and in the South China Sea as well as contesting Taiwanese sovereignty; and cracking down on domestic security issues in Hong Kong, Xinjiang, Tibet, and Inner Mongolia. At the same time, China has worked to rehabilitate its international reputation, which was dealt a bad blow by the coronavirus.

Diplomats charged with “telling China’s story well” (讲好中国故事, jianghao zhongguo gushi) have hit back hard against allegations of Chinese wrongdoing during the pandemic, calling such criticisms a “political virus” (政治病毒, zhengzhi bingdu) that must be fought alongside the coronavirus (PLA Daily, May 22). In June, the Chinese government published a white paper that sought to clarify the narrative of China’s triumph against COVID-19 and present its (airbrushed) experiences as a model for emulation (China Daily, June 8). In the context of this strategic propaganda push, China’s vaccine diplomacy becomes another tool for promoting its position as a responsible global leader amid the ongoing health crisis.

Origins of the Health Silk Road

In 2015, China’s National Health and Family Planning Commission released a three year plan to establish “health cooperation networks” with countries participating in China’s grand foreign policy Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) (China Daily, December 18, 2015). The Health Silk Road (HSR, 健康丝绸之路, jiankang sichou zhilv) was officially established as a joint initiative with the WHO at the beginning of 2017. Following a Belt and Road Forum for Health Cooperation headlined by the WHO Director-General later in the year, China published a “health silk road communiqué” signed by 30-odd countries, the WHO, and the Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (Xinhua, August 18, 2017). Despite its strong initial rollout, the HSR largely fell out of the public eye over the next two years.

The role of traditional medicine was noticeably championed during the initial rollout of HSR; China has long pushed applications of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) abroad as a means of bolstering its international soft power (and expanding a valuable domestic industry to new markets) (China Daily, January 19, 2017; Belt and Road News, March 27). Interestingly, it has continued to do so during the COVID-19 pandemic even though there is little to no scientific evidence of TCM’s efficacy in treating novel diseases (Xinhua: March 19, April 15, October 26).

It is worth taking a moment to note the difference between the HSR and other multilateral organizations for global health cooperation such as the WHO: China expert Nadegé Rolland has described the HSR as “not a multilateral institution per se,” but rather a “hub-and-spoke organism…[with] China at the center [and] multiple bilateral arms extending outward” (Axios, April 15). This distinction is important. While true multilateral organizations provide a relatively equalizing mechanism for inter-state diplomacy and dialogue, the balance of power in a hub-and-spoke model is weighted towards the center.

Revitalizing the HSR and BRI After COVID-19

The HSR has been connected with China’s strategic foreign policy Belt and Road Initiative since its beginnings. And like the BRI, the HSR has proven difficult to define or quantify. This vagueness has lent a certain narrative flexibility, allowing propagandists to freely utilize the term while simultaneously avoiding the need to adhere to concrete measurements of success. Analysts have noted the BRI’s reframing to address new economic goals amid a changing international situation in the wake of COVID-19 (China Brief, September 28). The HSR has been similarly revamped to fit Chinese propagandists’ evolving rhetorical needs in 2020.

The HSR was first referenced in connection with COVID-19 during a phone call between Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi and his Italian counterpart Luigi Di Maio on February 28 (MFA (China), February 28). Following this, Xi Jinping began alluding to the HSR in discussions of coronavirus-related aid with several heads of government in mid-March (Xinhua: March 17, March 21). On March 24, a People’s Daily commentary emphasized the renewed importance of HSR as a platform for BRI cooperation and as a means of contributing to global health governance (People’s Daily, March 24). Local media also explicitly tied China’s distribution of coronavirus aid to its BRI linkages (Sina, March 26).

As the pandemic began to spread around the world, China moved quickly to ship medical supplies to more than 120 countries (Xinhua, April 4). In some instances, but not all, COVID-19 aid shipments were organized via preexisting transit pathways connected along the BRI. For example, shipments of medical supplies to Argentina were coordinated by existing BRI partners that had previously been involved in building hydroelectric dams in Argentina’s Santa Cruz province, and China’s close public health cooperation with states like Saudi Arabia and Italy were facilitated by the countries’ memberships in the BRI (Xinhua, May 21; Belt and Road News, May 21; CGTN, August 26).

The Health Silk Road has also been explicitly connected with the Digital Silk Road (DSR), another lesser-known BRI program aimed at enhancing digital connectivity which has also been revitalized this year (Belt and Road News, May 20). Human rights watchers fear that as China touts its successful handling of the pandemic via the vehicle of the HSR, it may also seek to export related health surveillance technologies to other countries via the DSR.

Although a degree of public health surveillance is needed to mount an effective response to infectious diseases, China’s wide-ranging collection of sensitive personal data as part of its response to the coronavirus did not include adequate protections for citizens’ privacy. Additionally, cybersecurity experts have warned that the public health crisis contributed to an escalation of China’s already oppressive authoritarian surveillance regime, and that new surveillance technologies (such as the Health QR Code) are not likely to go away anytime soon even though China has largely controlled the domestic spread of the coronavirus.[4] In short, China’s surveillance regime underwent a massive expansion in response to the necessity of controlling COVID-19, and it seems likely that China will continue to leverage BRI linkages to export its repressive toolkit to authoritarian countries around the world as the pandemic continues.

Conclusion

Following China’s promise to invest in a long-awaited Africa CDC earlier this year, some had hoped that the HSR’s renewal earlier this year could drive China to learn from the lessons of past epidemics and work to overcome historic structural shortcomings in the developing world (The China Story, September 17). But the evidence of China’s bilateral vaccine diplomacy seems to indicate that China has adopted a dual strategy for cementing its position as a global health leader: simultaneously publicizing its involvement in multilateral initiatives to appear a responsible participant in the global system while also pursuing bilateral deals on the side that maximize its power and influence.

China was able to burnish its international reputation as a responsible global stakeholder by joining the COVAX initiative in October, but details of its subsequent participation in the multilateral group (such as the amount of financial support provided or contributions to COVAX’s procurement “pool” vaccine supply) remain murky. Because COVAX has so far failed to achieve its funding goals, it is unlikely that it will be able to supply much of the globe’s vaccine needs, and developing countries will still need to source at least a portion of their vaccine supplies elsewhere.

Crucially, China’s bilateral deals to supply vaccines to developing countries in Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America have bypassed international standards on vaccine development, raising major ethical concerns. They could also present an opportunity for Chinese suppliers to negotiate higher prices than pooled purchases would have achieved. A report by Nikkei Asia has also noted that vaccine guarantees of immunity to COVID-19 may be short-lived; countries may have to source repeated inoculations to keep their populations safe, creating longer-term dependencies on vaccine suppliers (Nikkei Asia, November 4).

Regardless of how it is done, supplying developing nations with a viable COVID-19 vaccine would mark a major triumph for China’s biopharmaceuticals industry, which has been historically wracked by quality scandals and previously served primarily domestic consumers.[5] China’s vaccine diplomacy stands to benefit the country economically and politically, underscoring the development of a global health system in which Chinese influence dominates.

Elizabeth Chen is the editor of China Brief. For any comments, queries, or submissions, feel free to reach out to her at: cbeditor@jamestown.org.

Notes

[1] The state-owned company Sinopharm has provided unproven vaccine candidates to students going abroad (Sixth Tone, October 27) and state employees deemed to be at high risk for exposure (New York Times, July 16). Meanwhile, a controversial vaccine candidate created in cooperation between CanSino Biologics and the PLA-affiliated Academy of Military Science has been approved for “limited use” by military personnel (Global Times, June 29). See also: Dyani Lewis, “China’s coronavirus vaccine shows military’s growing role in medical research,” Nature, September 11, https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-02523-x.

[2] Due to a lack of active coronavirus cases within the country, China’s vaccine researchers have had to go abroad to conduct Phase Three vaccine trials. As a result, Chinese biopharmaceutical companies have conducted vaccine trials in more than a dozen countries, including Peru, Argentina, Bahrain, United Arab Emirates, Egypt, Pakistan, Turkey, Morocco, Saudi Arabia, Bangladesh and Russia. See: Yojana Sharma, “China gambles with trust, transparency in race for vaccine,” University World News, October 10, 2020, https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20201010151810774.

[3] For a discussion on the failures of mask diplomacy see: Gerry Shih, “China’s bid to repair its coronavirus-hit image is backfiring in the West,” Washington Post, April 14, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/chinas-bid-to-repair-its-coronavirus-hit-image-is-backfiring-in-the-west/2020/04/14/8611bbba-7978-11ea-a311-adb1344719a9_story.html. And for a summary of vaccine deal-related foreign policy gains, see: Sui-Lee Wee, “From Asia to Africa, China Promotes its Vaccines to Win Friends,” New York Times, September 11, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/11/business/china-vaccine-diplomacy.html.

[5] See: “China’s COVID-19 Surveillance Toolkit” in Dahlia Peterson, “Designing Alternatives to China’s Repressive Surveillance State,” CSET, October 2020, https://cset.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/CSET-Designing-Alternatives-to-Chinas-Surveillance-State.pdf.

[6] For a discussion of some of the vaccine scandals which plagued China in 2016, 2018, and 2019, see (in chronological order): David O’Connor, “Vaccine Scandal Rocks China,” ChinaFile, May 4, 2016, https://www.chinafile.com/green-space/vaccine-scandal-rocks-china; Echo Huang, “China’s parents can’t even trust the country’s vaccines,” Quartz, July 23, 2018, https://qz.com/1333758/vaccine-scandals-erupt-in-china-on-tainted-milk-scandal-anniversary/; Joyce Huang, “Use of Expired Vaccine Sparks Public Scare in China,” VOA, January 16, 2019, https://www.voanews.com/east-asia-pacific/use-expired-vaccine-sparks-public-scare-china.