CMC Reshapes PLA Political Work System

Publication: China Brief Volume: 25 Issue: 19

By:

Executive Summary:

- The PLA’s new regulation on political cadres aims to reform a deeply entrenched political work system by emphasizing impartial personnel management and personal discipline.

- The regulation defines behavioral standards for political cadres across three main categories: core political logic, operational priorities, and personal conduct and leadership principles, while placing special emphasis on improving personnel management.

- Overall, the regulation reflects a broader reform of the PLA’s political work system, rather than a targeted purge of individual senior leaders. It identifies inappropriate interpersonal relationships and their downstream effects as key obstacles to professionalizing the personnel process.

- In essence, the regulation suggests that He Weidong and Miao Hua likely lost Xi Jinping’s trust due to shortcomings in political work and personnel management.

- By more extensively embedding political cadres into frontline operations on a larger scale, the new regulation can further reinforce command redundancy. This will ensure operational continuity through layered leadership and distributed command resilience.

On July 21, the PLA Daily announced new regulations aimed at imposing stricter standards and responsibilities on political cadres in the military (PLA Daily, July 21). The Regulations on Vigorously Promoting Fine Traditions, Thoroughly Eliminating Toxic Influences, and Reshaping the Image and Authority of Political Cadres (关于大力弘扬优良传统、全面肃清流毒影响 重塑政治干部形象威信的若干规定) seek to address entrenched problems within the military’s political work system, correct inappropriate personal relationships and their associated issues, and place personnel management at the center of reform.

The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Central Military Commission (CMC), which issued the regulations, did not publish their full text. This is consistent with recent practice, in which the PLA has withheld the full versions of regulatory documents. But the surrounding context suggests that the regulations are linked to ongoing purges within the military apparatus. CMC Chair Xi Jinping likely lost trust in senior political officers because they failed to deliver results in personnel management and in correcting long-standing institutional bad habits. Xi may leave these senior combat or political positions unfilled for the foreseeable future, as he needs time to assess whether the political work system is undergoing meaningful change and whether the officers it promotes can earn his trust.

A Moral Code to Stamp out Corruption

The new regulations consist of seven sections. So far, only the titles of four have been publicly released. These are strengthening political loyalty (强化政治忠诚), upholding Party principles (恪守党性原则), promoting fairness in personnel decisions (公道正派用人), and leading by example (身先示范). The PLA also has stated that the regulations contain 22 provisions, though it has dislosed none.

An analysis of 18 official articles published between July 21 and late September sheds some light on the content of the regulations. These include a seven-part series in the PLA Daily on “Establishing the Image and Authority of Political Cadres” (牢固立起政治干部形象威信系列谈), as well as other pieces in the dedicated column “Carrying Forward Fine Political Work Traditions and Setting a Good Example for Political Cadres” (践行政治工作好传统 立起政治干部好样子) (PLA Daily, July 21, July 21, July 22, July 23, July 24, July 24, July 25, July 28, July 29, July 30, July 31, August 8, August 16, August 24, August 29, September 6, September 13, September 18).

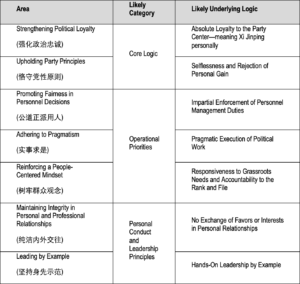

The regulations’ seven sections can be divided into three broader categories based on their substance. The first two sections relate to the core logic and principles underpinning military service. The next three concern operational priorities. And the final two discuss personal conduct and leadership principles (see Table 1 below).

The first section of the regulations discusses strengthening political loyalty. It explicitly demands loyalty to the Party Center. In other words, to Xi Jinping himself. One PLA Daily commentary warns that once loyalty is diluted or compromised, complex struggles and tests of competing interests can push cadres to betray their original aspiration to join the military and their oath to the Party. The article urges cadres to have higher standards and stricter discipline for implementing the “Chairman Responsibility System” (军委主席负责制) and to take the lead in rejecting corrupt political practices such as trading favors, engaging in bureaucratic maneuvering, and breaking unwritten rules. A historical example serves as a warning. In 1935, Zhang Guotao (张国焘), a founding member of the Chinese Communist Party, attempted to rival Mao’s leadership during the Long March. Zhang tried to persuade senior commander Zhu De (朱德) to defect, but Zhu refused, insisting on following the authority of the Party Center (Qiushi, May 16, 2018; PLA Daily, July 22). Zhang lost power and, in 1937, was purged.

The second section is upholding Party principles. This requires political cadres to act with selflessness and to reject any pursuit of personal gain. A PLA Daily article states that when individuals place personal interests above all else, they inevitably disregard the interests of the Party and the military. Political cadres must ground their conduct in Party discipline, speak honestly, and handle matters truthfully. The article illustrates this with a well-known example from 1980. That year, Huang Kecheng (黄克诚), then the Executive Secretary of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection, discovered that a long-serving subordinate had used public funds to host a banquet. Huang acted swiftly and, despite his personal ties to the errant official, took disciplinary action (CPC News, March 11, 2016; Qiushi, February 4, 2022; PLA Daily, July 23).

Table 1: Possible Content of the Seven Areas in the Regulation

The second part of the regulations contains three sections that focus on operational priorities. The first of these is promoting fairness in personnel decisions and the impartial execution of personnel management. As an article in the PLA Daily explains, officials must fully implement the Party’s criteria for selecting qualified officers. Political cadres must resist favoritism, nepotism, and vested interests to identify and assign capable officers in a timely and appropriate manner (PLA Daily, July 24). The next section focuses on adhering to the principle of “seeking truth from facts” (实事求是). It calls for pragmatic leadership in political work. According to the PLA Daily, this means that political cadres must take the lead in adopting a correct view of success. They must devote their energy to concrete results and practical work while avoiding the pursuit of short-term achievements, rigid bureaucratic attitudes, and obstructionist approaches to problem-solving (PLA Daily, July 25). The final section here concerns reinforcing a “people-centered mindset” (群众观念). This requires political work to reflect the needs of the PLA’s grassroots and withstand scrutiny from the rank and file. Relevant PLA Daily coverage emphasizes that political work, at its core, is mass work. Whether a political officer can reach the rank and file, engage directly with enlisted personnel, and address their concerns serves as a basic test of competence. Reaching again for inspiring historical analogies, the article cites a case from the Long March when political officers noticed that many soldiers were marching barefoot. They immediately came up with a plan to solve the problem and promptly directed political organs to guarantee the plan’s full implementation (PLA Daily, July 28).

The final two sections of the regulation are centered on personal conduct and leadership principles. The first of these concerns maintaining integrity in personal and professional relationships. It prohibits political cadres from engaging in exchanges of favors or pursuing private interests. According to the PLA Daily, a political officer’s every word and action reflects on the Party. Cadres must avoid flattery, sycophancy, and opportunism. They must uphold principled and disciplined relationships, remain alert to political rules and boundaries, and never trade away core values for personal gain (PLA Daily, July 29). The second section relates to leading by example. It calls on political cadres to personally carry out their duties rather than delegate or seek privilege. The PLA Daily asserts that CCP members have no right to special treatment, only the obligation to resist it. Political cadres must embody a spirit of hard work and self-sacrifice. Only then, the article argues, can they possess the moral authority and popular appeal to rally others to action (PLA Daily, July 30).

Structural Reforms Target Personnel Management Issues

Since 2023, the PLA has purged tens of senior military officers (China Brief, July 26). But the new regulations take the view that, at root, problems within the PLA’s political work system are mainly structural and cultural. The focus therefore should be on cultivating a better class of political officers, rather than on issues at the top of the military hierarchy. To provide guidance on how grassroots political officers should conduct themselves, the regulations have been supplemented by a series of eight case studies. None of these articles examine political work issues within the CMC or high commands. Most focus on improving operations and reinforcing personal discipline among political cadres.

Official reporting indicates that the central problem within the political work system lies not in finacial corruption but in inappropriate interpersonal relationships. This is reflected in the regulations themselves, of which only one section makes an explicit reference to financial issues and, even then, only as one element within a broader discussion of appropriate relationship boundaries. Commentaries in the PLA Daily and its online “Strong Military” (强军) forum explain that the regulations aim to draw red lines for political conduct, boundaries for the use of power, limits for social interactions, and warnings for clean governance (PLA Daily, July 21, July 24). Financial matters are just one part of this larger framework. By contrast, the provisions on political loyalty and Party principles stress that cadres must remain loyal only to the CCP Central Committee—meaning Xi Jinping personally—and must demonstrate absolute selflessness. The regulations also emphasize the importance of promoting talent without bias, pursuing truth over expediency, and ensuring that work passes the test of the grassroots.

The regulations also indicate that personnel management appears to be Xi Jinping’s top priority within the political work system. Promoting fairness in personnel decisions is one of the regulations’ seven sections. They also discuss more general work styles such as adhering to pragmatism and strengthening officers’ people-centered mindset. This signals that Xi places greater emphasis on personnel management than on other responsibilities traditionally assigned to political officers and sees it as crucial for rebuilding credibility. One of the published case studies perfectly encapsulates this emphasis. Instead of focusing on an individual political officer’s experience, it uses an example from a naval unit implemeting an aspect of the regulations to highlight the operational functions of the political work system itself (PLA Daily, August 24).

Grassroots Scrutiny, A Wait for New Leadership, and the Operational Role of Political Officers

Failures in personnel management appear to be central reasons for the dismissal of top PLA leaders involved in political work, such as He Weidong (何卫东) and Miao Hua (苗华), among others (China Brief, April 11). The new regulations’ focus on personnel management reinforces this interpretation. The lack of alignment between PLA officer conduct and Xi’s expectations are now forcing political officers to be subject to grassroots-level scrutiny. The Central Commission for Discipline Inspection’s authority over personnel matters also has been expanded to deal with certain cases (China Brief, May 23).

Where senior PLA leadership positions have been vacated in recent purges, Xi may not rush to fill them. A large number of high-ranking officers—including those responsible for political affairs, such as the CMC vice chairman for political work, the director of the CMC Political Work Department, and the Navy’s political commissar—have been removed from their positions. But if problems within the political work system responsible for managing personnel are as entrenched as these purges and the new regulations indicate, they will not be fixed by filling the positions with officers not vetted by a new evaluation system. This logic could explain why Dong Jun (董军), despite having served as Minister of National Defense for nearly two years, has not yet been appointed to the CMC: Xi is continuing to assess his reliability.

The regulations’ emphasis on pragmatism and leading by example effectively expands the operational responsibilities of political cadres, giving them even greater oversight than they had previously. This is made clear in the case studies, five of which highlight political officers directly participating in or leading frontline training and operational tasks. Some even describe political cadres temporarily assuming command positions or formally transitioning into commanding posts. While these accounts undoubtedly function in part as propaganda, they nonetheless reflect a growing expectation that political officers must strengthen their capacity for operational leadership. The PLA now appears to demand not only ideological discipline from its political cadres, but also greater hands-on command experience and mission-oriented competence.

Conclusion

Personnel purges within the political work system, the introduction of new behavioral standards for political cadres, and the evolving approach to promotions and personnel management are having a dual impact on the PLA. First, despite short-term blows to morale due to disruption of the promotion system, the reforms could ultimately boost morale if they succeed in eliminating deeply entrenched bureaucratic habits and restoring professional standards. Second, the political work system’s growing emphasis on operational competence—and the shift toward more pragmatic and mission-oriented political training—may enhance the PLA’s overall combat effectiveness. This is because the political apparatus now appears to reinforce—rather than merely monitor—the PLA’s operational readiness. By strengthening the role of political cadres at the front line, the PLA could enhance its command redundancy through stronger layered leadership and distributed resilience.

The latest regulations on their own are unlikely to eradicate corruption in personnel promotions altogether. Corruption remains a problem throughout the Party-state system, not just in the military, and it will not be possible to remove it from one area without doing so throughout the rest of the country. The reforms nevertheless have the potential to improve the institutional mechanisms and internal culture of the PLA’s political work system. They may also raise the standard of personnel management and bolster the professional capacity of the PLA officer corps.