Cold Winter – China’s Envoy to Pyongyang Leaves Without Results

Publication: China Brief Volume: 17 Issue: 15

By:

North Korea’s steady drumbeat of missile launches and provocations kept relations with China and the United States tense for most of the year. Harvest time and preparations for the Korean People’s Armies’ winter training cycle have paused the missile launches, but heading into winter, there are no signs of a thaw in relations (Korea Times, November 20; see also Jamestown, October 11).

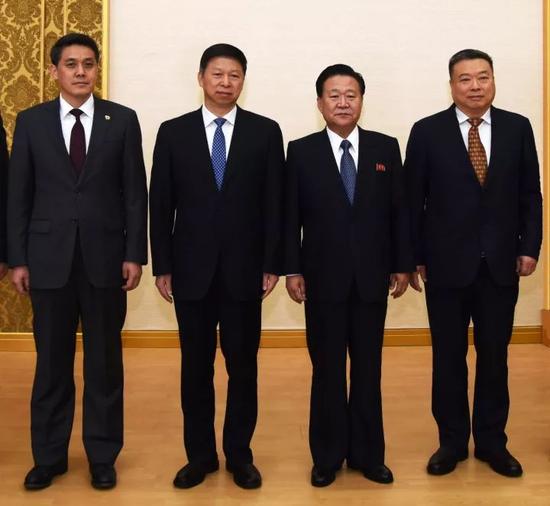

In the wake of President Trump’s visit to China and pledges of closer cooperation to address the security on the Korean Peninsula, Beijing dispatched veteran diplomat Song Tao (宋涛), head of the Chinese Communist Party’s International Liaison Department (ILD; 中联部), to Pyongyang. However, Song’s four-day visit appears to have been fruitless. Song returned to Beijing without meeting with Kim Jong-un, as he was widely expected to, and with little but vague promises of improved relations.

As the head of a Communist Party body, rather than state-affiliated organization, Song came as an emissary looking to improve the Party-to-Party relationship between the CCP and Workers’ Party of Korea which in the case of North Korea is even more important than state-to-state relations. Song is also a trusted international relations expert, having previously served as the Vice-Minister of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, with over a decade of foreign affairs experience in various MFA roles. Song was also involved in relations with South Korea, and met with the envoy of then-newly-elected President Moon Jae-in in May (Xinhua, May 19).

Because of his experience, Song has been in charge of handling high-level contacts with North Korea before. In 2016, Song met with his North Korean counterpart, Ri Su-yong (리수용), in Beijing, ahead of the latter’s meeting with Xi Jinping (FMPRC, June 1, 2016; FMPRC, May 31, 2016). Similar to Song’s visit, Ri’s intention for visiting Beijing was to consult with the CCP and provide briefings on the results of the Worker’s Party of Korea’s 7th Congress—its first in 36 years.

During this visit, Song met with Choe Ryong Hae, a senior military figure considered to be Kim Jong-un’s second-in-command. While an important member of North Korea’s ruling party, it is a far cry from the last visit from a senior Chinese official. In 2015, Liu Yunshan, the now-retired member of the Politburo Standing Committee and propaganda chief watched North Korea’s National Day Parade side-by-side with Kim Jong-un (China Brief, March 8, 2016).

Despite China’s obvious disapproval of Kim’s provocations, Beijing has deliberately worked to improve relations on both ends of the peninsula and kept communications open. However, the failure of Kim to meet with Song—or to meet with Xi personally—indicates the North Korean leader clearly views China as less a partner and more a threat.

On November 21, the U.S. Department of Treasury announced an expanded list of sanctions against companies within North Korea or doing business with it (Treasury, November 21). Several of the entities and individuals targeted by the sanctions are based in China, further tightening the lockdown on economic relations between the two countries.

Mirroring the slump in trade between China and North Korea, China Airlines, one of only two carriers connecting North Korea to the outside world, ceased flights between Beijing and Pyongyang due to insufficient numbers of passengers (Sohu, November 22).

For its part, North Korea appears to have no interest in ceasing its nuclear ambitions. South Korea’s National Intelligence Service (NIS) believes that “depending upon North Korean leader Kim’s determination, a nuclear test is possible any time” though the intelligence service also said North Korea is struggling to build ICBMs capable of reentering the atmosphere (Korea Times, November 20; Korea Times, November 17).

While the expansion of sanctions will clearly stem the flow of additional cash to North Korea, forcing its government to make hard decisions about allocating money to keep the government running or invest in weapons. Nonetheless, observers should remember China’s own experience with building nuclear weapons.

Perhaps no other country knows the struggle of building a nuclear deterrent amid economic calamity better than China. China launched several extraordinarily expensive defense projects during the twenty years between the Great Leap Forward (1958–1962) and Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), which saw dramatic economic decline and internal political chaos. Despite these tough periods, China successfully tested a nuclear bomb in 1964 (China.org.cn, October 16, 2007; SCMP, November 20). Work on a nuclear submarine began in 1958 but the first submarine was only completed twenty years later in 1974.

Observers at the time, including the Hong Kong-based China News Analyses, noted the colossal folly of such plans. The programs, spearheaded by Marshal Nie Rongzhen and General Zhang Aiping, used resources from the country at a time when it could least afford it. Some of the projects, particularly the nuclear attack and ballistic missile submarines, offered little in the way of tangible deterrence. However, facing the threats of the United States and later the Soviet Union, China prioritized nuclear deterrence at all cost. The international community hopes that sanctions and diplomatic leverage will force the North Korean leadership to reconsider its pursuit of a nuclear deterrent. However, it is worth keeping in mind that China, when faced with similar hardship, also chose to build nuclear weapons.

For more information on North Korea check out the Jamestown Foundation’s North Korea Backgrounder