CNP Part II: Seven National Development Strategies

Executive Summary:

- Since 1992, the Party has enshrined seven national development strategies in the Party Charter, embedding development of “comprehensive national power” (CNP) at the heart of its approach to governance.

- In the first phase (1992–2008), three strategies focused on strengthening science and education, as well as sustainable development, based on the assessment that economic and technological competition would become the dominant aspect of international struggle.

- A second phase, beginning in 2008, sought to address uneven development across the system and continue building CNP in the context of an increasingly unstable international environment.

- Throughout this period, the United States has been viewed as the main adversary. This was most striking in 2013, when Xi argued that strategic competition with the United States was unavoidable and that the country needed to double down on self-reliance—a remarkable assessment to make at the height of U.S.-PRC engagement and cooperation.

- The Military-Civil Fusion Development Strategy, unveiled in 2015, is perhaps the most significant of the seven. Described as essential for optimizing the other strategies and enabling the country to move to the center of the world stage, it calls for establishing a singular, national strategic system to advance simultaneous economic and national defense strength.

Editor’s note: This is the second article in a four-part series. To read the first article, click here. To read the third article, click here.

In 1992, the Chinese Communist Party leadership saw a world in transition. The 1992 Government Work Report pronounced that the “old pattern of the world” (世界旧的格局) had ended but that a new one, centered on multipolarity, had not yet emerged. In the meantime, during what General Secretary Jiang Zemin (江泽民) heralded a “new era” (新时代), hegemony and power politics had become the biggest source of instability in the international system (Xinhua, February 16, 2006; Xinhua, August 1, 2008; Study Times, January 4, 2021). “For the relatively long-term,” Jiang told assembled diplomats in 1993, “the United States is still our main diplomatic adversary” (在今后一个较长时期内,美国仍是我们外交上打交道的主要对手) (Reform Data, July 7, 1993). And as he explained in his report to the 16th Party Congress, competition in comprehensive national power is becoming increasingly fierce” (国际局势正在发生深刻变化。世界多极化和经济全球化的趋势在曲折中发展,科技进步日新月异,综合国力竞争日趋激烈) (Xinhua, August 1, 2008).

The problem, in Jiang’s view, was that the People’s Republic of China (PRC) was relatively weak compared to the United States. This assessment was based on measures of comprehensive national power (CNP; 综合国力). CNP, according to scholars in the PRC who study it, is the aggregate strength of a state based on an array of factors across a variety of domains (China Brief, September 5). The most fundamental goal of a CNP system is to enhance the country’s capacity for survival and development. Its ultimate goal is achieving national rejuvenation (Huang Shuofeng, August 2006). [1]

The Party believed—and still believes—that the United States dominated the global system in terms of CNP. In the early 1990s, Jiang assessed that CNP competition based on economic and technological strength had become the “dominant aspect of international struggle” (国际斗争的主导方面)—an assessment would persist until the 20th Party Congress thirty years later (Reform Data, January 13, 1993). [2] To ensure the PRC’s survival and, as Jiang explained in the 14th Party Congress Report for the first time, to achieve its ultimate goal of national rejuvenation, it had to build up strength in the core elements of CNP to rival, and perhaps one day surpass, the United States (Party Member’s Net, October 9, 1992).

In pursuit of this goal, the Party embedded CNP development at the heart of its approach to governance. An addition to the 1992 Party Charter that also appeared in the 14th Party Congress Report stated that any course of action must be decided based on whether it is conducive to the development of productive forces, whether it raises the living standards of the people, or whether it enhances CNP. This framework is known as the “Three Advantages” (三个有利于). Initially outlined by Deng Xiaoping in his 1992 “Southern Tour” speech, it formed the ideological basis for the entire period of reform and opening and has appeared in nearly every party congress report since.

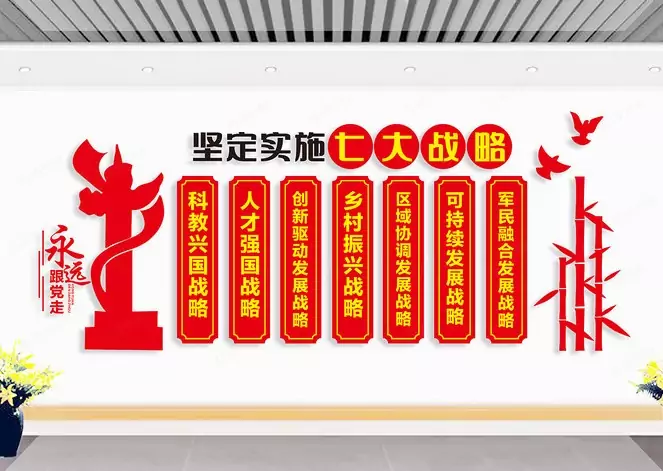

As part of this approach, the Party launched and implemented a series of seven national development strategies. Formed on the basis of assessments of CNP development, these offer guidance to senior leaders in determining the allocation of resources to address newly emerging contradictions within the PRC’s development model. They are listed as follows, in the order in which they appear in the Party Charter (but not in chronological order of when they were implemented) (Party Members Net, October 22, 2022):

- Rejuvenation through Science and Education Development Strategy (RSEDS; 科教兴国战略)

- Talent Strong Country Development Strategy (TSCDS; 人才强国战略)

- Innovation-Driven Development Strategy (IDDS; 创新驱动发展战略)

- Rural Revitalization Strategy (RRS; 乡村振兴战略)

- Regional Coordinated Development Strategy (RCDS; 区域协调发展战略)

- Sustainable Development Strategy (SDS; 可持续发展战略)

- Military-Civil Fusion Development Strategy (MCFDS; 军民融合发展战略)

Phase One (1992–2008): Building CNP Under American Hegemony

Rejuvenation through Science and Education Development Strategy

In 1995, the CCP launched the “Rejuvenation through Science and Education Development Strategy” (RSEDS; 科教兴国战略). This was the first of three national development strategies unveiled across the ensuing decade designed to underpin pursuit of CNP. It was based on an understanding that science and education are critical to human resource power under CNP measures and that the “quality” (素质) of human resources is a decisive factor in economic growth. [3]

Talent development is central to building high-quality human resources and thus is core to the RSEDS. As Xi said at a 2023 Politburo study session, “talent competition has become the core of [CNP] competition. Educating people for the Party and the country is the key to realizing the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation and the second centenary goal amid great changes unseen in a century” (人才竞争已经成为综合国力竞争的核心。为党育人、为国育才,是百年未有之大变局下实现中华民族伟大复兴和第二个百年奋斗目标的关键所在) (China Education News, June 1, 2023).

Official guidance on the RSEDS explained that S&T progress had become “the main driving force for economic growth” (经济增长的主要推动力) and “the focus of international economic competition and [CNP] competition” (国际竞争和综合国力较量的焦点) (Worker’s Daily, May 3, 1996). Following the strategy’s launch, the Ministry of Education implemented a series of efforts to push the development of a university system capable of achieving its goals. These included Project 211 and Project 985, which sought to develop world-class institutions of higher education. [4] In 2016, as the PRC prepared to launch a second wave of policies to drive the development of the education system, Xi explained that “when education is strong, the country is strong” (教育强则国家强). He went on to announce that the leadership had made a “strategic decision” (战略决策) to accelerate the construction of world-class universities to enhance the nation’s core competitiveness” (增强国家核心竞争力) (People’s Daily Online, December 9, 2016). This led to the “Double First Class” (双一流) strategy, which launched in 2017 (Xinhua, October 18, 2017).

The RSEDS was intended to drive development, not only of science and technology (S&T), but also of economic and national defense strength, and, as a second order effect, international influence strength (Reform Data, May 26, 1995, June 14, 1996). In the Party’s conception, the interrelated nature of CNP as a giant, complex system means that success in the implementation of the RSEDS drives many of the other national development strategies outlined below.

Sustainable Development Strategy

The Sustainable Development Strategy (SDS; 可持续发展战略) was also launched in 1996, and was included in the 15th Party Congress Report the following year (NDRC, March 17, 1996 [archived link]; (People’s Daily Online, September 12, 1997). Emphasizing core elements of CNP, it called on the PRC to balance economic development, social development (including the “quality” of the people), and natural resources, and to promote ecological and environmental protection. Official guidance from 2003 also called for management of the flow of resources across the system (State Council, January 14, 2003; China Brief, September 5).

Recognition of the risks of unbalanced development emerged in the early 1990s as a priority for the PRC government to address (Ministry of Ecology and Environment, September 22, 2009). SDS documentation explains that the strategy is centered on resolving several contradictions: between fast economic growth and environmental disaster, rapid development and lagging social development, economic and social development across different regions, and between some existing policies and regulations and the actual needs for implementing sustainable development (State Council, January 14, 2003).

The SDS also informed the 2004 launch of Hu Jintao’s signature “Harmonious Society” (和谐社会) policy, which sought to ensure the promotion of harmony between humanity and nature. Hu’s policy promoted the “coordinated development of urban and rural areas” (城乡协调发展) that later became foundational to the Regional Coordinated Development Strategy and the Rural Revitalization Strategy (see below) (State Council, October 11, 2006; Xinhua, November 15, 2013).

Talent Strong Country Development Strategy

The Talent Strong Country Development Strategy (TSCDS; 人才强国战略), occasionally rendered as the “Strategy to Develop a High-Quality Work Force,” was launched in 2003. It builds on the RSEDS but focuses more on the people themselves. The people have long considered within the CCP (and most Socialist systems) as a resource of the state, and the quality of the population is a core element of CNP.

The centrality of talent was identified early by CNP scholars. Huang Shuofeng (黄朔风) listed the “science and technology team,” comprising scientists, engineers, and technical staff, as a key sub-index of S&T power (Huang Shuofeng, 1992, p. 169). This was echoed by Hu Jintao in a 2008 speech, who said that improving the “ideological and moral quality and scientific and cultural quality of the entire nation, especially in the creation of a large team of high-quality talents” (提高全民族的思想道德素质和科学文化素质,尤其必须造就一支庞大的高素质人才队伍), was important for enhancing CNP and international competitiveness (Xinhua, May 4, 2008). Xi reiterated the importance of talent as a resource in a 2013 speech, explaining that “talent competition has become the core of [CNP] competition” (人才竞争已经成为综合国力竞争的核心) (Xinhua, October 21, 2013).

Phase 2 (Post-2008): Amassing CNP As Rivalry Develops

The second phase of development strategies crafted to orient the PRC toward pursuit of CNP started around 2008. It began with a baseline assessment that the PRC had become the second most powerful country in the world and was quickly closing the gap with the United States. It also assessed that the world was growing less stable. These two evolving perspectives meant the PRC had to rapidly resolve domestic problems by addressing a new primary contradiction and uneven development across the system. The Party introduced four development strategies to address those challenges over the next decade. While largely focused on alleviating domestic issues, the strategies also have been implemented with a view to reshaping the PRC’s international environment. As the scholar Yan Xuetong (阎学通) explained in 2014, Beijing seeks to change the character of the international system, and “changes in [CNP] are the first factor affecting changes in the international pattern” (综合国力变化是影响国际格局变化的第一要素) (Yan Xuetong, 2014 [archived link]). [5]

Innovation-Driven Development Strategy

The first of the four second-phase strategies, the Innovation-Driven Development Strategy (IDDS; 创新驱动发展战略), was unveiled in 2012 in the 18th Party Congress Report (Xinhua, November 17, 2012). The strategy focuses on promoting indigenous innovation and reducing reliance on external actors. As Xi emphasized in a 2013 speech, S&T innovation “is the strategic support for improving social productivity and [CNP]” (是提高社会生产力和综合国力的战略支撑) (People’s Daily, October 2, 2013). This description also appeared in the “Outline” of the IDDS issued in 2016, which described S&T innovation capabilities as the core support of national strength, economic transformation, and national defense modernization—three key elements of CNP (Xinhua, May 19, 2016).

The CNP literature ties leading-edge technology capabilities to S&T strength, but also to international influence. This is because being a dominant technology producer has spillover effects, from shaping supply chains to setting global norms and rules for technology use. Xi also made this connection in 2013, saying that innovation-driven development is “driven by the [domestic] situation” (形势所迫) and that the country’s economic aggregate, social productivity, CNP, and S&T strength had stepped up to a new level (Xinhua, October 1, 2013). In 2023, the State Council Information Office (SCIO) commemorated the decennial of the IDDS, noting that the country had expanded research and development (R&D) expenditure from $145 billion to $455 billion, with R&D intensity rising from 1.9 percent to over 2.5 percent. The article went on to explain how IDDS implementation was enabling the PRC to provide technology globally, again emphasizing the downstream foreign policy power and international influence power effects of the IDDS (SCIO, March 10, 2023). The investments appear to be paying off. According to the World Intellectual Property Organization, as of 2025, the PRC has finally broken into the top 10 most innovative countries, up from 43rd in 2010 (WIPO, September 16).

While recognition of the need for independent innovation goes back to at least the 1990s, a new international environment in 2012 demanded a new urgency. As Xi explained, “in the increasingly fierce global competition for [CNP], we have no more choices and must take the path of independent innovation” (在日趋激烈的全球综合国力竞争中,我们么有更多选择,非走自主创新道路不可). He warned that if the PRC was not at the forefront of innovation, it would always be behind (People’s Daily Online, March 3, 2016). This stark framing reflected anxieties about relying on S&T from international partners. Even though S&T strategies had long emphasized the importance of international collaboration, Chinese scholars and Party leaders had expected that the United States eventually would try to fully contain the PRC’s rise. “In the past,” Xi said, “everybody wanted to sell you technology. Now that you have developed, no one is willing to sell you technology because they are afraid you will become bigger and stronger. We can have no illusions about the introduction of new and high technologies. Core technologies, especially national defense technologies, cannot be bought with money” (过去你弱的时候谁都想卖技术给你,今天你发展了,谁都不愿卖技术给你,因为怕你做大做强。在引进高新技术上不能抱任何幻想,核心技术尤其是国防科技技术是花钱买不来) (Xinhua, February 28, 2016).

The IDDS was therefore a forward-looking recognition that the strategic competition with the United States that emerged around 2018 was unavoidable. One remarkable feature of this assessment is that it was made at the height of U.S.-PRC engagement and cooperation under the umbrella of the Strategic and Economic Dialogue. Yet by 2022, the Party experts’ earlier assessment seemed to have come to pass. A Chinese Academy of Social Sciences report noted that technological competition with the PRC had become “an important part of the U.S. diplomatic strategy” (美国外交战略的重要内容) (CASS, “Annual Report on International Politics and Security (2022)”, 2022, p.58).

Regional Coordinated Development Strategy

The Regional Coordinated Development Strategy (RCDS; 区域协调发展战略) launched in 2014. It was framed as “an inevitable requirement and support for promoting high-quality development” (推动高质量发展的必然要求和重要支撑) and Chinese-style modernization (People’s Daily, February 1, 2024). A 2018 State Council Opinion claimed that this new mechanism for coordinated regional development would significantly reduce regional development gaps and play an important role in building a modern economic system to meet the people’s growing needs for a better life (Xinhua, November 29, 2018).

A focus of development since the 1990s, the RCDS was elevated to a national strategy in 2014 to address the new primary contradiction identified in 2017 and what Xi Jinping characterized as “unbalanced” and “uncoordinated” development across the Chinese system, especially between different regions. An information campaign in 2022 and 2023 emphasized that unbalanced development “mainly refers to the unbalanced development of various regions, fields, and aspects which restricts the improvement of the overall development level” (主要是各区域各领域各方面存在失衡现象,制约了整体发展水平提升;发展不充分) (Economic Times, September 20, 2023).

The RCDS seeks to correct imbalances stemming from Deng’s maxim to allow some to get rich first, with an emphasis on the Special Economic Zones along the east and southeast coast of the PRC. These were the first areas to open up to the world in the 1980s, leading to rapid expansion of development and wealth in those regions that was not matched across the rest of the country (Xinhua, February 25, 2024).

Military-Civil Fusion Development Strategy

Elevated to a national strategy in 2015, the Military-Civil Fusion Development Strategy (军民融合发展战略) is fundamentally a systems design strategy. It reflects the giant, complex system Huang Shuofeng described in his 1992 and 2006 books, as well as the focus of CNP on the allocation of resources across an entire system. It also owes much to the lasting impact of Qian Xuesen (钱学森) and his team at National Defense University that did so much of the cybernetics work in the 1980s that frames systems thinking in the PRC today.

Under the MCFDS, the CCP seeks to establish a “National Strategic System and Capabilities” (NSSC; 国家战略体系和能力). This is a singular, national strategic system formed through a “deep fusion” of 12 sub-systems, comprised of six systems within the nominally civilian economic system and six more within the national defense system. Between these sub-systems, bureaucratic and other barriers are designed to be eliminated, allowing for the free flow of technology, finance, talent and other national resources (all key indices of resource strength, economic strength, and S&T strength under the CNP rubric). In designing this system, the MCFDS is critical to advancing simultaneous economic and national defense strength. It also is intended to help address concerns with unbalanced development across the PRC.

The MCFDS has important implications for the PRC’s status in the international system. As one set of academics noted in 2017, elevating the development of military-civil fusion into a national strategy “is the inevitable logic for China to move to the center of the world stage” (Jiang Luming et al., 2017). [6]

According to PRC scholars, the NSSC will enable the optimal pursuit of all seven national development strategies, with the “capabilities” drawn from the constituent elements of CNP. At least two Chinese analysts writing on the NSSC have explained the national strategic capabilities of the NSSC as a translation process; that is, translating current CNP into future CNP (Zhan Jiafeng, 2005; PLA Daily, October 10, 2014). [7]

Rural Revitalization Strategy

The Rural Revitalization Strategy (乡村振兴战略; RRDS) was announced at the 19th Party Congress, at which time it was also added to the Party Charter (Xinhua, September 26, 2018). The CCP considers rural revitalization a historic task related to the construction of a modem socialist country (People’s Daily, April 1, 2018). [8] Rural economics and the livelihood of the rural population—which now exceeds 500 million—has been a central focus of the Party since Mao’s rural reforms in the 1950s. Xi explained this importance in 2023, emphasizing that without agricultural power, which is a key sub-index within CNP elements, the country will not develop into a modem, powerful socialist country (Xinhua, March 15, 2023).

The 2018–2022 Rural Revitalization Strategic Plan described its rationale as resolving the main contradictions in Chinese society in the new era and ensuring achievement of the “Two Centenary Goals” and the “China Dream of the Great Rejuvenation of the Chinese Nation.” This indicates that assessments of national conditions (the new primary contradiction) drive strategy for CNP development (Xinhua, September 26, 2018). By way of explanation, the People’s Daily wrote that “at present, China’s economic strength and [CNP] have increased significantly, and it [now] has the material and technical conditions to support agricultural and rural modernization” (当前,中国经济实力和综合国力显著增强,具备了支撑农业农村现代化的物质和技术条件) (People’s Daily, December 19, 2017). This framing of national development in terms of CNP is further evidence to suggest that the indices identified by CNP-focused scholars continue to be used to understand the PRC’s national conditions. CNP studies are concerned primarily with how resources can be allocated across the overall system. By recognizing that the PRC has the requisite CNP to support rural modernization, the CCP leadership can allocate resources appropriately. As such, CNP is both the target for modernization and the means to achieve it.

The RRDS reflects multiple areas of the theoretical framework of CNP, including Wu Chunqiu’s (吴春秋) 1998 systems analysis of the importance of balanced development across national sub-systems and the basic definition of CNP as a reflection of development strength. According to Huang Shuofeng and others, development across these systems relies on political strength within the constituent elements of CNP and the ability of the government to correctly assess the systems and marshal resources across those systems to ensure their even development.

Conclusion

The seven strategies outlined above are deeply interrelated in practice. Three of them, the RSEDS, the TSCDS, and the IDDS, all work together to develop resources and capabilities that drive the hard power elements of CNP, including economic strength, S&T strength, resource strength, and national defense strength. They are frequently referred to in CNP literature as the “three-in-one” strategy, or the “trinity” (三位一体). For instance, the 20th Party Congress Report calls for deeply implementing these strategies, explaining that education, science and technology, and talents are the “basic and strategic support” (基础性、战略性支撑) for comprehensively building a modern socialist country (Xinhua, October 25, 2022). [9] Figure 1 above illustrates the integration of the seven national development strategies developed to address the PRC’s modernization.

For decades, leadership speeches, central Party documents, and national development strategies have been emphatic about the criticality of S&T and talent in order to prevail in competition with the West. They have also highlighted the need to collaborate internationally to develop domestically in those areas. This theme, prevalent in the TSCDS, IDDS, and MCFDS, demonstrates both a Chinese vulnerability (reliance on the West to advance S&T-driven agendas for CNP) and a complicated vulnerability in the United States and other advanced technology producing countries, where Chinese (and foreign) talent helps drive innovation. However important the contributions it makes to the United States and other technology ecosystems might be, that talent remains defined within the CNP literature as a resource for CNP competition that the CCP will draw from to prevail in strategic competition.

Development strategies codified in the Party Charter remain an important signpost to PRC priorities for development and signals of continued PRC reassessments of the country’s national conditions. The Party continues to actively implement all seven, despite significant international pressure on the MCFDS from 2017–2021. This pressure led the CCP to remove references to the MCFDS from most national-level documents, but it did not remove it from the Party Charter, despite other modifications to that document in 2022. The MCFDS began to reemerge in Party documents in 2024 as international pressure subsided. Analyzing the seven national development strategies in the Party Charter provides a map of how Chinese leaders assess progress in their pursuit of rejuvenation through different stages of development. This in turn helps shed light on how Chinese leaders likely assess the country’s domestic conditions for survival and development, and, ultimately, progress toward rejuvenation and CNP development.

This article reflects the sole views of the author. They do not reflect the views or policies of the U.S. Government, the Department of Defense, or the Department of the Navy.

Notes

[1] Shuofeng Huang, Rivalries Between Major Powers: A Comparison of World Power’s Comprehensive National Power [大国转量:世界主要国家综合国力国际比较] (Beijing: World Affairs Press, 2006), 63.

[2] This passage framed international struggle as being based on CNP. It goes on, however, to state that “military means” still play an important role.

[3] Huang Shuofeng, Comprehensive National Power Theory [综合国力论], (Beijing: China Academy of Social Sciences Press, 1992), 103; Huang, Rivalries Between Major Powers, 2006, 228–9; Men Honghua [门洪华], Hu Angang [胡鞍钢]. “The Rising of Modern China: Comprehensive National Power and Grand Strategy” [现代中国之崛起:综合国力与大战略]. Strategy & Management, no. 3 (2002). 5–6.

Population control is a key aspect of managing human resources, according to the SDS. Along these lines, the 10th Five-Year Plan laid out efforts to “control the population size and improve the quality of the population” (控制人口增长,提高出生人口素质) (State Council, March 15, 2001).

[4] Project 211 (211 工程) was launched to raise the level of research standards of high-level universities and cultivate strategies for socio-economic development by establishing 100 world-class universities by the beginning of the 21st Century. Between 1995 and 1998, the 112 universities admitted to Project 211 received 70 percent of national research funding and 80 percent of doctoral students. See Fei Shu, Cassidy R. Sugimoto, and Vincent Larivière, “The Institutionalized Stratification of the Chinese Higher Education System,” Quantitative Science Studies 2, No. 1 (2021): 327–34; Michael A. Peters, “The Double First-Class University Strategy: 双一流,” Educational Philosophy and Theory 50, no. 12 (2018): 1075–79.

[5] Xuetong Yan, How to Understand the International Situation and My Country’s Foreign Policy [如何认识国际形势和我国外交政策], Secretary Work 10 (2014).

[6] Luming Jiang, Weigai Wang, and Zuchen Liu, Discussion on Military-Civil Fusion Development Strategy (Beijing: People’s Publishing House, 2017), 34.

[7] Jiafeng Zhan [詹家峰], “A Brief Analysis of the Relationship Between National Strategic Capabilities and Comprehensive National Power” [国家战略能力与综合国力关系浅析], Modern International Relations [现代国际关系], no. 4 (2005).

As Zhan writes, “National strategic capabilities serve as the bridge connecting existing CNP with future CNP, forming a chain: existing CNP → national strategic capabilities → future CNP” (国家战略能力是沟通和连接现有综合国力与未来综合国力的桥梁,即现有综合国力→国家战略能力→未来综合国力) … “CNP forms the foundation for national strategic capabilities, and national strategic capabilities also exert a reciprocal influence on CNP” (综合国力是国家战略能力形成的基础,而国家战略能力对综合国力也具有反作用) … “national strategic capabilities exert a powerful constraining influence on CNP, impacting its expansion and development” (国家战略能力又对综合国力发挥着强大的制约作用,影响着综合国力的提升与发展). Multiple Chinese scholars have used this framing of the link between CNP and national strategic capabilities. For instance, the PLA Daily article cited here uses almost verbatim language.

[8] Jinping Xi. “On “Three Rural Areas” Work (Beijing: Central Party Press, 2022), 275.

[9] This relationship also reflects the Party’s evolving view of Chinese modernization: Deng first declared that S&T are the primary productive forces; Jiang added that talent is the key resource; and Xi combined these with innovation as the key driving force.